April 2022 REPORT 1

HP-2022-12

Addressing Social Determinants of Health:

Examples of Successful Evidence-Based Strategies

and Current Federal Efforts

Amelia Whitman, Nancy De Lew, Andre Chappel, Victoria Aysola, Rachael Zuckerman,

Benjamin D. Sommers

KEY POINTS

Long-standing health inequities and poor health outcomes remain a pressing policy challenge in

the U.S. Studies estimate that clinical care impacts only 20 percent of county-level variation in

health outcomes, while social determinants of health (SDOH) affect as much as 50 percent.

Within SDOH, socioeconomic factors such as poverty, employment, and education have the

largest impact on health outcomes.

SDOH include factors such as housing, food and nutrition, transportation, social and economic

mobility, education, and environmental conditions. Health-related social needs (HSRNs) refer to

an individual’s needs that might include affordable housing, healthy foods, or transportation. This

report provides select examples of the evidence in several of these areas.

Housing – Studies show strong evidence of the benefits for “housing first” interventions that

provide supportive housing to individuals with chronic health conditions (including behavioral

health conditions). Benefits include improved health outcomes and, in some cases, reduced

health care costs. In addition, interventions that reduce health and safety risks in homes, such as

lead paint or secondhand smoke, can also improve health outcomes and reduce costs.

Food and Nutrition – Efforts to improve food access through healthy food environments, public

benefit programs, health care systems, health insurers, and evidence-based nutrition standards

can lower health care costs and improve health outcomes.

Transportation – Enhanced built environment interventions including sidewalks, bicycle

infrastructure, and public transit infrastructure can make physical activity easier, safer, and more

accessible. Non-emergency medical transportation has been shown to be cost-effective by

increasing use of preventive and outpatient care and decreasing use of more expensive care.

Social and Economic Mobility – Multiple randomized trials show that cash payments to families

and income support for low-income individuals with disabilities are associated with better health

outcomes. Early childhood care and education are also associated with positive health outcomes.

Social Service Connections – Some studies of care management and coordination using multi-

disciplinary teams that support HRSNs show reduced total cost of care and improved health

outcomes, but the evidence overall on these effects is mixed.

Building on this evidence base, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is taking a

multifaceted approach to address SDOH across federal programs through timely and accessible

data, integration of public health, health care, and social services, and whole-of-government

collaborations, in order to advance health equity, improve health outcomes, and improve well-

being over the life course.

April

1, 2022

April 2022 REPORT 2

INTRODUCTION

Despite significant investments to improve access to high-quality health care, health inequities in the United

States persist by race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, and disability, as well as by economic and

community level factors such as geographic location, poverty status, and employment. Black, Latino

*

,

American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN), Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islanders (AANHPI),

and LGBTQ+, individuals, people who live in rural areas, and people with disabilities fare worse than their

White, heterosexual, and urban counterparts and people without disabilities. These disparities exist for many

health outcomes, including infant and maternal mortality, heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, chronic

illness, disability, cancer, mental illness, substance use, and overall life expectancy.

1-10

While opportunities to advance health equity through clinical care continue to be important,

11

addressing the

ways in which social determinants of health (SDOH) increase or decrease the risk of poor health outcomes is

critical to improving the nation’s health and wellbeing. SDOH are the conditions where people are born, live,

learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life

outcomes.

12

When one or more of these conditions pose challenges, such conditions can become risk factors

for poor health outcomes. SDOH are fundamental social and structural factors that touch people’s lives and

impact their wellness and longevity. Health and wellness are shaped by and within overarching systems,

including structural racism, ableism, homophobia, and transphobia; and broad neighborhood and community

structures including physical safety, environmental quality, and occupation-related hazards. Educational

attainment, income, and the stress of financial hardship, along with discrimination due to nativity and racial or

ethnic origin, disability, sexual orientation, and gender identity, are key determinants that influence a variety

of more proximal factors (such as access to affordable housing) that impact the risk of morbidity, mortality,

and health throughout the life course.

Social and structural factors play a critical role in driving disparate health outcomes. One study estimated that,

on average, clinical care impacts only 20 percent of county-level variation in health outcomes, while SDOH

affect as much as 50 percent of health outcomes.

13

More specifically, socioeconomic factors alone may

account for 47 percent of health outcomes, while health behaviors, clinical care, and the physical environment

account for 34 percent, 16 percent, and 3 percent of health outcomes, respectively.

14

Moving from the county

level to the individual level, a given person’s physical health, behavioral health, and well-being are also

influenced by factors that are specific to the individual. At the individual level, we use the term health-related

social needs (HRSNs) to refer to an individual’s needs that might include affordable housing, healthy foods, or

transportation. An unequal distribution of SDOH is the root cause of HRSNs at the individual level. For

example, a particular community may lack abundant affordable housing, but local individuals may experience

housing needs differently. Distinguishing between SDOH and HRSNs is critical for developing measures,

evaluating data sources, assessing evidence and especially for formulating policy responses.

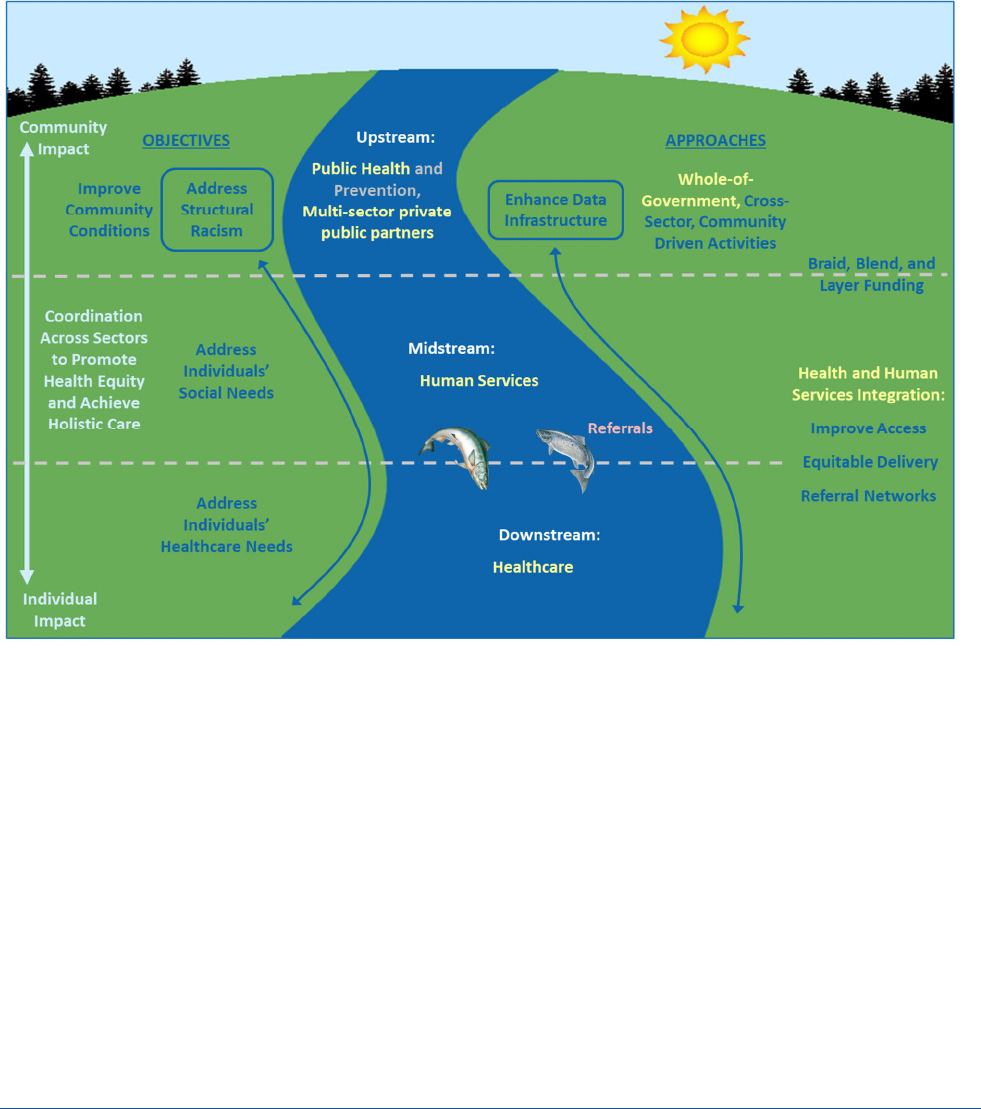

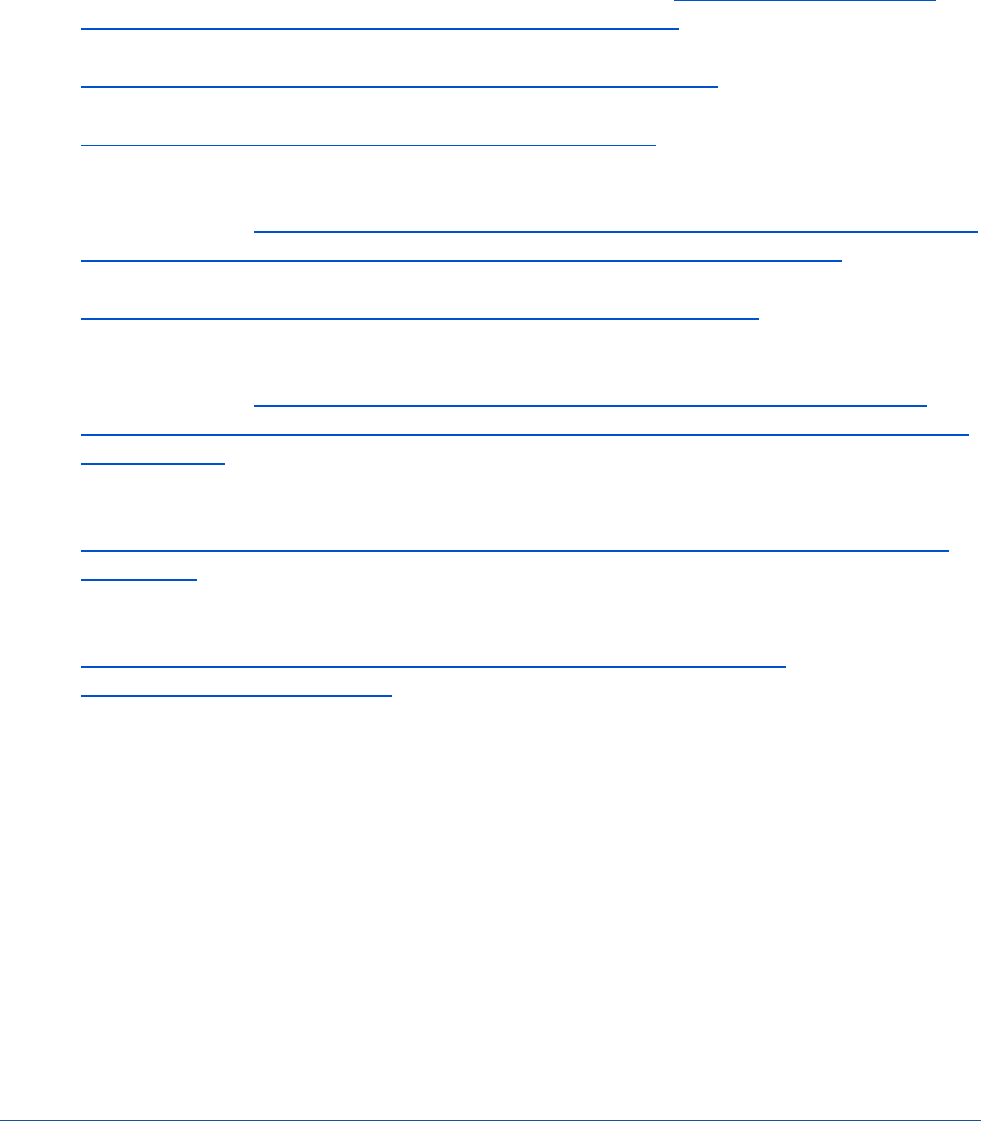

Figure 1, below, provides a pictorial representation of the SDOH and HRSNs ecosystem. The diagram includes

three segments depicting different points at which there are opportunities to address SDOH, with the river

representing the level of action and primary actors, and the banks representing the objectives and approaches

for each segment. Importantly, addressing structural racism and enhancing data infrastructure, noted in

boxes, are key factors for success. In the upstream segment are the underlying social and economic conditions

that create differences in SDOH. Interventions relevant to this segment apply at the community level and

attempt to address the root causes of socioeconomic and health inequities (such as poverty, employment, and

education). The midstream segment is human services (i.e., social service providers and community-based

organizations) that address individuals’ HRSNs in order to mitigate the effects of SDOH. The downstream

segment focuses on individual health care, which may refer or connect an individual to assistance for a social

_______________________

*

This brief uses the term “Latino” to refer to all individuals of Hispanic and Latino origin.

April 2022 REPORT 3

need. While the diagram indicates that human services and health care primarily address the needs of

individuals, the bi-directional arrows indicate the need for coordination across each of the three segments.

The Figure depicts the nation’s investment in health care spending as downstream of investments in

community conditions (including public health) and social services. While health care in the U.S. is by far the

most highly resourced sector of the three, improving health outcomes requires adequate support for all three

sectors. To develop comprehensive strategies and policies to address SDOH, it is important that those involved

in each of the three segments partner with each other to identify community-based approaches towards

addressing the underlying root causes of health disparities.

Figure 1. Social Determinants of Health Ecosystem

Note: Adapted from Castrucci B, Auerbach J. Meeting Individual Social Needs Falls Short of Addressing Social Determinants of Health.

Health Affairs Blog. January 16, 2019

This brief provides a high-level overview of select strategies to address SDOH and HRSNs that have

demonstrated success in reducing impediments to health and well-being, improving health outcomes, or

lowering health costs, as well as a discussion of some of the current HHS efforts to address SDOH and improve

the conditions that impact health and longevity among the American people. This brief surveys the evidence

on successful interventions designed to address SDOH and the HRSNs of people at various points in the

lifespan including infancy, childhood, adulthood, and older age; people who live in particular areas, such as

major cities or rural communities; and people with particular conditions such as asthma, HIV, and others. It

should be noted that interventions may improve health outcomes, utilization, or costs for one group but not

necessarily for other groups. In many cases, data on health outcomes are not available, so data on health care

utilization, costs, or healthy behaviors are presented as proxy measures. These may or may not represent

improved health and well-being and is therefore a critical limitation in evaluating impacts. As noted in the

conclusion, additional research is needed on the longer-term impacts of many of these interventions.

Conversely, even when interventions don’t improve utilization measures or lower health care costs, there may

April 2022 REPORT 4

be value in the intervention in the form of improved health outcomes, well-being, or long-term impacts not

included in the studies’ time horizon. A key prerequisite for both addressing health disparities related to SDOH

and HRSNs and measuring progress after intervention implementation is a more robust and interconnected

data infrastructure to support evidence-based policies and better identify improved outcomes associated with

such policies.

This brief is not intended as a comprehensive review of all of the evidence on SDOH and HRSNs. It highlights

only a few of the many interventions that have been evaluated and largely focuses on selected domains where

there is at least some evidence to suggest potential health effects. There is a rich literature on SDOH and

HRSNs, some of which is referenced throughout this paper, and several systematic reviews and resource

libraries survey the full landscape of this evidence base.

15-21

Important methodological challenges exist in assessing the effects of interventions for SDOH and HRSNs. At

the community level, randomized designs are rare and the evidence is often not sufficient to make causal

conclusions. In addition, many interventions focus on individuals who have experienced adverse outcomes,

such as a hospitalization, high health care costs, or other negative health or social events. In such cases,

simple pre-post assessments, without a control or comparison group, will often suffer from regression to the

mean – the phenomenon in which people experiencing higher-than-expected outcomes in one period (e.g.,

total health care spending) will typically experience closer-to-average results in the subsequent period simply

by chance. Other challenges include lack of comprehensive data for both health and social outcomes; lack of

large sample sizes, particularly for subgroup analyses; and differences in unmeasured characteristics between

those who participate in HRSN interventions and those who do not. In addition, methods for evaluating SDOH

and HRSNs are not static and research innovation continues to evolve to enhance our understanding of the

effects of intervening on SDOH and HRSNs. For these reasons, this brief, which provides a broad view of the

current state of the research, attempts to highlight whenever possible the study design and the relative

strength of the evidence, preferentially reporting results from randomized trials and natural experiments with

defined comparison groups. This brief also references several systematic reviews that use consistent,

transparent, and scientifically rigorous methods, which provide the opportunity to look across many studies at

once in order to understand what interventions work and under what conditions.

EVIDENCE REGARDING SELECTED SOCIAL DETERMINANTS

Safe and Stable Housing

Safe and stable housing has been associated with improved health and well-being. For example, housing

instability among families has been associated with fair or poor caregiver and child health, maternal depressive

symptoms, child lifetime hospitalizations, and household material hardships, such as food insecurity and

foregone care.

22

The Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF), which provides guidance on available

scientific evidence about community-based health promotion and disease prevention interventions,

recommends tenant-based housing voucher programs to improve health and health-related outcomes.

23

Permanent supportive housing (PSH), a model which pairs affordable housing assistance with voluntary

supportive services,

*

has been shown to be effective in improving housing stability.

24,25

Existing evidence

reviews have also found strong evidence of the benefits of providing supportive housing to individuals with

chronic health conditions, including behavioral health conditions, with studies demonstrating reduced

_______________________

*

Services provided as part of PSH are designed to build independent living and tenancy skills and connect individuals to needed

services. These supportive services can include case management, mental health services, primary health services, substance abuse

treatment, employment services, and parenting skills. National Alliance to End Homelessness. Permanent Supportive Housing.

https://endhomelessness.org/ending-homelessness/solutions/permanent-supportive-housing/ and Corporation for Supportive

Housing. Understanding Supportive Housing. https://www.csh.org/toolkit/understanding-supportive-housing/

April 2022 REPORT 5

inpatient, emergency department (ED), and long-term care utilization, and in some cases improved health

outcomes or reduced overall costs.

26,27,28

Housing interventions for adults experiencing homelessness who have chronic illnesses (such as heart disease,

diabetes, renal failure, cirrhosis, asthma, and HIV) have been shown to reduce hospitalizations, hospital days,

and ED visits.

29

Individuals with HIV experiencing homelessness who received permanent housing with

intensive case management had better outcomes than those receiving typical discharge planning, including

higher one-year rates of survival with intact immunity and a higher percentage with undetectable viral loads

than the usual care group.

30

The study also found reduced utilization among high cost individuals. A 2012

study looking at individuals with chronic medical illnesses experiencing homelessness in Chicago found that

those who received a housing and case management intervention experienced 2.6 fewer hospitalized days, 1.2

fewer ED visits, 7.5 fewer days in residential substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, 9.8 fewer nursing home

days, and 3.8 more outpatient visits each year, compared to individuals who received usual care.

31

Evidence is more mixed regarding the impact of housing on total cost of care. However, in a systematic

review, the CPSTF found that the economic benefits of PSH with Housing First programs in the United States

exceed the cost of intervention, with a substantial portion of savings attributable to health care.

32

In the 2012

study discussed earlier, among Chicago patients with chronic medical illnesses experiencing homelessness,

those receiving a housing and case management intervention had an estimated annual cost savings of $6,307

compared to the control group, accounting for health care, legal, housing, and case management costs.

Another study in Los Angeles compared the average monthly cost savings for persons in supportive housing

based on various characteristics and found the highest cost savings among individuals with HIV/AIDS, mental

illness and/or SUD, and those who were 45 to 65 years old. Conversely, costs increased among individuals who

worked in the last three years, as the average monthly cost savings for public services did not offset the cost of

providing supportive housing.

33

Ensuring housing is safe also has positive health impacts. There is evidence that improving individual’s existing

housing via home improvements or modifications improves outcomes.

34-39

A study comparing children with

public insurance living in redeveloped public housing (distressed and dilapidated urban public housing rebuilt

into lower density, townhome-style communities), non-redeveloped public housing, and nonpublic housing

found that children living in non-redeveloped public housing were 39 percent more likely to have repeat visits

within one year for acute care services unrelated to their initial visit, while there was no difference between

those in redeveloped and nonpublic housing.

40

Fixing housing issues related to health impacts can also

improve outcomes. An intervention that provided dust mite covers, a professional house cleaning, and roach

bait and trays to households of children with asthma found that the intervention group had lower dust mite

levels and better functional severity scores compared to a delayed intervention group, though overall asthma

severity scores did not change.

41

Healthy home environment assessments, which use home visitors to assess

and remediate environmental health risks within the home, have also been shown to decrease use of urgent

care and improve health outcomes.

42

A review by the CPSTF found such interventions resulted in a median

reduction of 21 symptoms days per year and 0.57 asthma acute care visits per year among children and

adolescents.

43

Smoke-free housing policies can also improve health outcomes through reduced exposure to

secondhand smoke.

44

Further, an 2014 analysis of national state cost savings associated with prohibiting

smoking in subsidized housing estimated that such prohibitions in all US subsidized housing would result in

$310 million in annual cost savings from reductions in secondhand smoke-related health care.

45

In some cases, housing modifications have also been associated with health care cost savings. Community

Aging in Place, Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE), which provides home repair and modifications

relevant to individuals’ functional goals along with other efforts to improve their self-care ability and functional

goals, resulted in $867 less Medicaid spending per month in 2018, on average, for dual-eligible beneficiaries

over age 65 who experienced difficulties with at least one activity of daily living (ADL).

46

Another study found

April 2022 REPORT 6

that the CAPABALE intervention reduced ADL disabilities by 30 percent in five months.

47

Modifications like

those done by CAPABLE can support individuals with a disability in living safely at home.

48

Reducing lead

exposure in homes by eradicating lead paint hazards from older homes and removing lead drinking water

service lines have also demonstrated health savings and benefits in health (measured via quality-adjusted life

years, QALYs). A 2019 analysis estimated that eradicating lead paint hazards from older homes of children

from low-income families would provide $3.5 billion in future benefits, including $60 million in health savings

and $110 million in health benefits, while removing lead service lines would result in $10 million in health

savings and $30 million in health benefits.

49

Nutrition and Food Access

Having healthy food available and affordable in food retail and food service settings allows people to make

healthier food choices. When healthy foods are not available, people may settle for foods that are higher in

calories and lower in nutritional value. Many strategies can contribute to healthy food environments,

including applying nutrition standards in childcare facilities, schools, hospitals, and worksites; providing

incentives for supermarkets or farmers’ markets to establish their businesses in underserved areas; and having

nutrition information and caloric content on restaurant and fast-food menus.

50,51

School-based interventions that combine meal or fruit and vegetable snack interventions with physical activity

interventions for elementary school students (through grade 6) increase students’ physical activity, modestly

increase their fruit and vegetable consumption, and decrease the prevalence of overweight and obesity.

52

Intervention approaches reviewed and recommended by the CPSTF to promote good nutrition include

community-based digital health and telephone interventions to increase healthy eating and physical activity;

digital health and telephone interventions to increase healthy eating and physical activity among students at

institutions of higher education; gardening interventions to increase vegetable consumption among children;

home-delivered and congregate meal services for older adults; and worksite digital health and telephone

interventions to increase healthy eating and physical activity.

53

For example, their review of community-based

digital health and telephone interventions to increase healthy eating and physical activity found that these

interventions resulted in a median 1.12 percent weight reduction, 10.25 milligrams/deciliter triglycerides

reduction, 4.00 milligrams/deciliter total cholesterol reduction, and 1.00 mmHg diastolic blood pressure

reduction.

54

Public benefit programs providing food assistance have been associated with lower health care costs, lower

health care utilization, and improve health outcomes.

55,56

However, it should be noted that most studies on

the impacts of such programs compare individuals who have enrolled in a given program versus those who

have not, and are subject to confounding due to differences between such individuals, which prevents drawing

any conclusions on cause and effect. A 2017 study of low-income adults participating in the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) found an association between SNAP participation and lower health care

expenditures, with approximately $1,400 lower expenditures per year among SNAP participants.

57

A 2018

study found 5.8 percent lower expenses among older adult SNAP participants who were hospitalized as

compared to hospitalized older adults without SNAP, as well as 1 percent lower odds of hospitalization for

each $10 increase in SNAP monthly benefit amounts among individuals dually eligible for Medicare and

Medicaid.

58

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) also has

been associated with improved maternal and child health outcomes, including reduced likelihood of preterm

births, lower odds of mortality within the first year, and reductions in disparities in low birthweight, extended

infant hospitalizations, and NICU outcomes, though with similar methodological limitations.

59,60,61

In addition,

an analysis of the National Health Interview Study found that respondents who participated in WIC were less

likely to forego or delay filling a prescription, skip medication doses, or take less medication than prescribed

due to costs.

62

The Older Americans Act (OAA) funded nutrition services is also associated with reduced health

care utilization and improved health outcomes for older adults. A study of OAA funded nutrition services

April 2022 REPORT 7

found that lower-income older adults who participated in the congregate meal program were significantly less

food insecure than nonparticipants, and 61 percent of home-delivered meal participants and 42 percent of

congregate meal participants indicated they would skip meals or eat less if the program was not available.

63

Individuals receiving home-delivered meals had greater improvements in anxiety and self-rated health, and

reduced rates of hospitalizations and falls compared with individuals on waiting lists.

64

Efforts to increase access to food via food pharmacies (pharmacies, health care clinics, or hospitals that store

and dispense healthy food

65

), food prescription programs (prescriptions from doctors for healthy foods that

can be used to subsidize the purchase of these items through community partners

66

), and home-delivered

meals, which are often funded through health care systems or health insurance, have been associated with

lowering health care costs and health care utilization.

67,68

Beginning in January 2016, a Geisinger Health

Systems hospital offered diabetic patients prescriptions for five days of breakfast and dinner ingredients per

week at their Fresh Food Farmacy, along with other supportive services. HbA1c levels (which indicate the level

of sugar in an individual’s blood) decreased by 20 percent among participants and Geisinger estimated that

every percentage point decline in HbA1c levels saved approximately $8,000 in health care costs, compared to

an annual investment in the program of $1,000 per patient per year; notably, however, this study did not

include a comparison group.

69,70

Similarly, health clinic produce prescription programs that provide funds to

purchase fresh produce from farmer’s markets have also found significant improvements in health outcomes,

including lower body mass indices (BMIs) among participants and improved glucose control among diabetic

participants, as well as improved patient-provider relationships.

71,72

Another intervention that has been shown

to improve outcomes is home-delivered meals. The provision of three free, nutritionally balanced meals,

seven days a week, to Medicaid beneficiaries in Philadelphia and southern New Jersey found a significant

decrease in total health care spending, fewer inpatient visits with shorter length of stays, and a greater

number of discharges home rather than to acute care facilities, compared to a similar group of Medicaid

beneficiaries who did not receive these services.

73

Another study found that, as compared to matched

nonparticipants, beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid participating in a food delivery

program had fewer emergency department visits and lower medical spending.

74

Transportation

Transportation systems help ensure that people can reach everyday destinations, such as jobs, schools, healthy

food outlets and health care facilities, safely and reliably.

75

Transportation issues impact individuals’ ability to

obtain needed medical care, with 3.6 million people in the U.S. missing medical services due to transportation

issues annually.

76

Transportation barriers to accessing medical care are complex and include transportation

infrastructure, transportation costs, vehicle access, distance and time burden, and transportation policy.

77

Non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) is one way to address some of these issues, including

transportation cost and vehicle access. NEMT has been shown to be cost-effective by increasing preventive

and outpatient care and decreasing more expensive care.

78

In a 2008 survey of Medicaid beneficiaries in New

Jersey, Louisiana, and Michigan receiving dialysis, SUD treatment, or diabetic wound care who used NEMT to

attend medical appointments, 58 percent of respondents indicated that they would make none of their

treatment appointments if NEMT were not provided.

79

Based on the results of this survey, study authors

estimated that per respondent, per month, Medicaid avoided $3,423 in costs for dialysis patients and $792 in

costs for wound care patients based on appointments that would likely be missed if not for NEMT, but did not

save on SUD treatments, as NEMT costs more than the additional medical costs from missed SUD treatments.

Another study comparing the costs and benefits of providing NEMT to individuals who lack access to

transportation found that for all 12 of the medical conditions analyzed, providing additional NEMT was cost-

effective, and it was cost-saving for four conditions (prenatal care, asthma, congestive heart failure, and

diabetes).

80

Cost-effectiveness was determined by establishing cost estimates for the provision of NEMT and

comparing the per capita cost of care for well-managed patients and poorly-managed patients for each

condition, accounting for additional factors such as QALYs. While NEMT is provided as a standard Medicaid

April 2022 REPORT 8

benefit, as of February 2022, four states have demonstration programs that waive provision of these

benefits.

81

Increasing access to safe, equitable public transportation infrastructure can also help address some of the

transportation barriers to accessing medical care and is also associated with positive health behaviors and

other positive health impacts. Public transportation is safer than travel in passenger vehicles, with motor

vehicle crashes being the leading cause of death for people ages 1-34.

82,83

In addition, air pollution from motor

vehicles contributes to adverse respiratory and cardiovascular health effects.

84

Public transportation is also

associated with increased access to health care and healthy food as well as improvements in mental health

and physical activity levels.

85,86

A study comparing train commuters to car commuters found that train

computers walked an average of 30 percent more steps per day and were four times more likely to walk

10,000 steps per day.

87

Similarly, a systematic review found an additional 8-33 minutes of walking per day

attributable to public transportation use.

88

However, given the disparities in traffic-related pedestrian death

rates, it is important that safe walking routes are included in efforts to support public transportation

infrastructure.

89

Further, a review from the CPSTF found that built environment strategies that combined one

or more interventions to improve pedestrian or bicycle transportation systems with one or more land use and

environmental design interventions increased physical activity.

90

Social and Economic Mobility

Social and economic factors such as socioeconomic status, income levels, poverty, and educational attainment

are fundamental drivers of poor health outcomes because they facilitate or impede access to important

resources that affect health outcomes directly and through multiple mechanisms.

91

In a study of societal

health burden and life expectancy, social and economic factors accounted for two of the three largest impacts

on health and life expectancy. Experiencing poverty or near poverty (living at incomes below 200 percent of

the federal poverty level) imposed the greatest burden and lowered quality-adjusted life expectancy more

than any other risk factor, with 8.2 QALYs lost per person exposed over his or her lifetime.

92

Poverty limits

opportunities and access to resources conducive to healthy behaviors, affects the physical “built”

environment, and limits service availability within communities, all of which have independent effects on

health outcomes.

93,94

Further, the cumulative effect of poverty over the life course also matters. For example,

the greater the number of years a child spends living in poverty, the more elevated the child’s cortisol levels

and the more dysregulated the child’s cardiovascular response to acute stressors.

95

These changes may impact

children’s cognitive development and chronic disease development, with larger exposures increasing the risk

of adverse outcomes later in life.

96

Cash transfers aimed at increasing income and reducing poverty can be particularly impactful for improving

health outcomes.

97

A recent meta-analysis examining health effects of randomized social experiments in the

United States identified seven cash-transfer interventions and found that they were associated with

improvement in self-rated health, though not with smoking status or obesity.

98

For example, the Stockton

Economic Empowerment Demonstration, a universal basic income experiment in Stockton, CA, gave randomly

selected residents $500 per month for two years with no strings attached, which measurably improved

participants' overall well-being and physical and emotional health.

99

Another income maintenance experiment

in Gary, IN, found that supplemental income provided to mothers was associated with higher birth weights for

their children in the absence of any health intervention, with the supplemental income linked to greater

changes in birth weight than tobacco use or race.

100

In addition, a study of low-income American Indian

children in families that received an annually increasing supplemental case income benefit found that by the

fourth year of the program, formerly poorly resourced children’s level of psychiatric symptoms was

comparable to those of children who were never poor.

101

April 2022 REPORT 9

Tax credits and supplemental income support for low-income individuals with disabilities also reduce poverty

and are associated with better health, including improved birth outcomes, maternal mental health, and

perceptions of health.

102,103

By reducing poverty and increasing income for working families, the Earned

Income Tax Credit (EITC) has been linked to positive health outcomes, particularly for infants and

mothers.

104,105

The EITC has led to improvements in infant health, including overall increases in birth weight

and reductions in low birth weight rates.

106,107

A study of the association between the EITC and health

outcomes found that compared to similar households that were not eligible for the credit, families eligible for

the credit were more likely to have all of their children covered by health insurance.

108

The same study also

found that infant mortality was lower in states with greater EITC penetration. The magnitude of this

relationship was strong: each 10-percentage point increase in EITC penetration (within or between states) was

associated with a 23.2 per 100 000 reduction in infant mortality rate (P = 0.013). Studies also show greater

health improvements when larger, more generous EITC benefits are available.

109

Supplemental Social Security

Income has also been associated with health improvements. A quasi-experimental study on Supplemental

Social Security Income (SSI) that examined within-state changes to maximum SSI benefits found that an

increase of $100 per month in the maximum benefit reduced mobility limitations among older adults.

110

In addition to programs providing economic support, educational supports such as high-quality preschool

programs also have been shown in studies to improve health outcomes.

111

Early childhood education is

associated with improved child development and can serve as a protective factor against future disease and

disability.

112

A review of research on early childhood education programs found that model programs, such as

Abecedarian, the Perry Preschool Project, and the Infant Health and Development Program, improved health

and health behaviors, including reduced smoking, improved cardiovascular health, and improved metabolic

health among participants in adulthood, compared to controls.

113

The review also found that such programs,

as well as Head Start, a federally-funded nationwide preschool program for low-income families, were

associated with reductions in depression and disabilities in adolescence and early adulthood.

Social Service Connections

In studies of programs that use multiple types of providers, such as social workers, nurses, physicians, and case

managers, to offer services that coordinate care across provider types and assist individuals with managing

their health care conditions and HRSNs some studies have found reductions in total health care spending and

health care utilization, and improved health outcomes, while in other cases results have been mixed.

114,115

Health Homes, which provide comprehensive care management, care coordination, health promotion, patient

and family support, and referral to community and social support services to individuals with multiple chronic

conditions or a serious mental illness, have been associated with improvements in linkages to SDOH-related

services, reduced ED utilization and inpatient admissions, and improvements in performance on process of

care measures among the first 11 states to launch the program.

116

Other models that provide linkages to social services and supports have been successful as well. However,

several evaluations have noted the need to do more than refer individuals to social services and supports. For

example, an evaluation of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Accountable Health Communities

model, which connects beneficiaries to community resources, found that only 14 percent of beneficiaries

referred to social service navigation had their needs resolved, while 33 percent were lost to follow up, 4

percent were connected to resources but their needs were unmet, 10 percent opted out after accepting

navigation, and 8 percent of needs could not be met.

117

Evidence suggests when partnerships are coordinated and well-funded, they are more likely to be successful.

WellCare Health Plans, Inc., a national managed care health plan that primarily serves patients in Medicaid,

Medicare, or dually eligible for both programs, in 2011 launched WellCare “CommUnity” Health Investment

Program, which included grants to social service providers and referred members and non-members to the

April 2022 REPORT 10

funded partners. Patients for whom a social barrier had been removed as a result of a referral to WellCare

CommUnity partners were more likely to have a better BMI, a better medication assessment score, and to

schedule and go to their annual primary care visit than patients without an intervention or referral.

118

Further,

as of 2017, these services provided through WellCare CommUnity partners generated $3,200 in per member

per year savings, including $3.47 health care savings for every $1 invested in the program. In addition, studies

have found improved outcomes when health systems partner with community-based organizations (CBOs) to

provide social services. For example, one study concluded that Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) were

more likely to succeed in integrating SDOH when they implemented networking initiatives that connect them

to CBOs.

119

Another study found that hospitals in Hospital Service Areas that performed well on ambulatory

care-related hospitalizations, readmission rates, and average reimbursements per Medicare beneficiary had

deeper and more consistent collaboration with CBOs that provided social services.

120

Similarly, partnerships

between hospitals and Area Agencies on Aging (AAA), which coordinate and offer services such as case

management, home-delivered meals, and transportation that help older adults who desire to remain in their

homes were associated with a $136 reduction in average annual Medicare spending per beneficiary between

2008 and 2013, as well as a significant reduction in hospital readmissions within a year.

121,122

Studies looking at the use of Community Health Workers (CHWs, frontline public health workers who are

trusted members of a community and have a close understanding of the community in which they are

serving

123

) to connect individuals to health or social supports have found reductions in Medicaid spending and

utilization of ED visits and an increase in use of ambulatory care.

124

For example, a randomized trial of adults

participating in ACOs found that individuals with contact with a CHW were less likely to experience a hospital

readmission within 30 days of discharge.

125

Among women with depression, women enrolled in a CHW

intervention had a reduction in the frequency of high-cost encounters and lower average total charge

amounts, compared to women enrolled in an enhanced screening and referral control group.

126

ILLUSTRATIVE EXAMPLES OF ACTIONS HHS IS TAKING TO ADDRESS SDOH

There are many efforts underway across HHS to address SDOH and HRSNs, several of which are highlighted

below. Table 1 shows illustrative examples of the relationship between the HHS agency initiatives described

below and the evidence base described in the preceding section. While many of these initiatives are in

progress and do not yet have completed evaluations at this time, in many cases, agencies are planning to

conduct evaluations of the programs discussed in order to document the programs’ successes, challenges, and

opportunities for improvement.

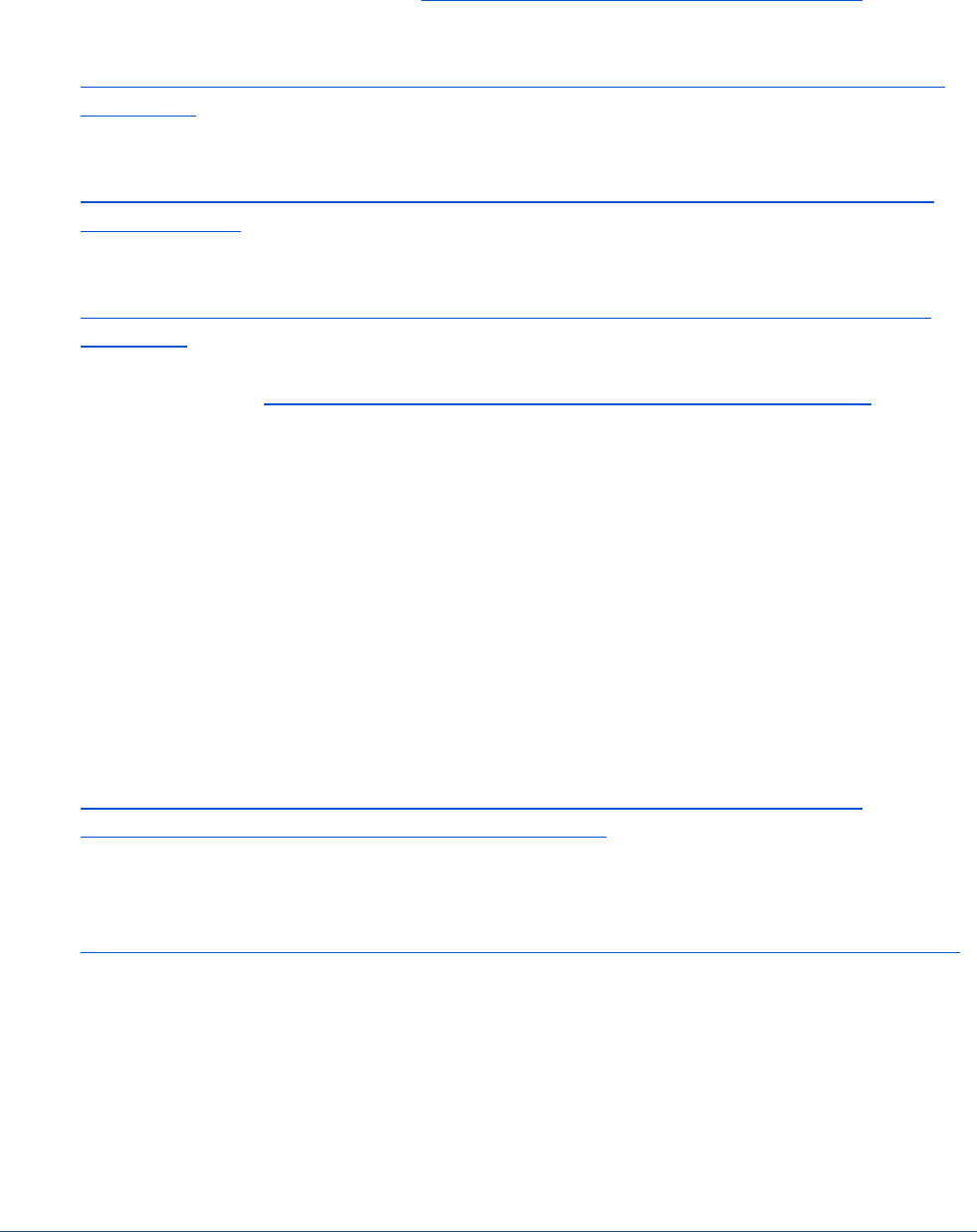

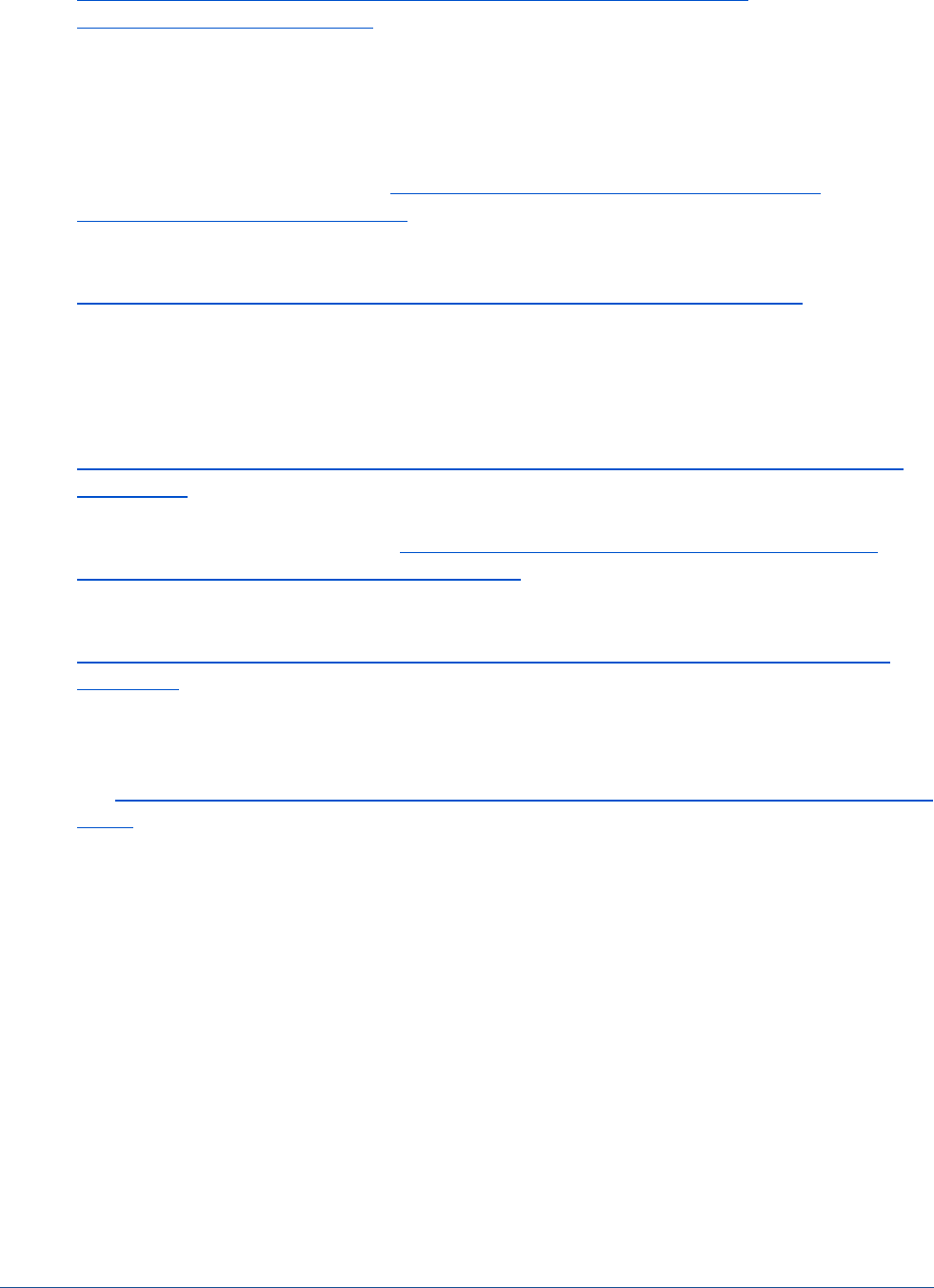

Table 1: Selected Evidence-Based Interventions Used In HHS Agencies: Illustrative Examples

*

AGENCY CMS HRSA CDC ACL ACF SAMHSA

Housing Related Services X X X X X

Home Modifications and

Improvements

X X X X

Food Access X X X X

Non-Emergency Medical

Transportation

X X X

Public Transportation X X

Case Management & Social

Service Connection

X X X X

Community Health Workers

X

X

X

X

Social and

Economic Mobility

X

X

Note: This table is not an exhaustive list of HHS activities in these areas and also does not necessarily reflect specific

funding or designated programs in each area.

_______________________

*

Agencies included may have additional programs that support evidence-based interventions listed on this table.

April 2022 REPORT 11

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Medicaid: Though Medicaid rules limit spending on non-medical services, nearly all states have implemented

at least some policies or initiatives to address HRSNs through their Medicaid programs for various populations.

In January 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a State Health Official letter

identifying opportunities for states to better address SDOH under Medicaid and CHIP and to support states

with improving outcomes and lowering costs by addressing SDOH. Using a variety of mechanisms, including

using section 1905(a) State Plan Authority, Home and Community Based Services (HCBS), section 1115

demonstrations, section 1945 Health, and managed care contract requirements, among others, states are

addressing HRSNs, including housing-related services and supports, non-medical transportation, home-

delivered meals, educational services, employment, community integration and social supports, and case

management.

127

Section 1905(a) State Plan Authority: States have used Section 1905(a) to establish peer supports and

case management services, which are then used to link beneficiaries to HRSN supports. As of 2018, 19

states indicated that case management is a covered benefit in their program, and 36 indicated that

targeted case management is a covered benefit (though this benefit may be provided under section

1915(g)

*

).

128,129

Home and Community Based Services (HCBS): Several states have utilized HCBS to implement

housing-related services, including 46 states with section 1915(c) waivers;

†

four states with section

1915(i) benefits; and eight states with section 1915(k) benefits as of 2021.

130,131

For example,

Minnesota is using section1915(i) state plan authority to provide housing stabilization services to

certain individuals that are experiencing homelessness or are at risk of becoming homeless.

132

In their

first year, the state reported that they served 7,203 individuals.

Section 1115 Demonstrations: As of 2021, 25 states have utilized the flexibility provided by section

1115 demonstrations

‡

to address HRSNs, such as housing-related services, nutrition, transportation,

and interpersonal violence.

133

For example, CMS recently approved an 1115 waiver for California’s

Medicaid program (Medi-Cal) to launch California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM), which

seeks to integrate the Medi-Cal program with other social services through a “no wrong door”

approach that couples clinical care with Medicaid reimbursable nonmedical services, including housing

supports, medical respite, personal care, medically tailored meals, and peer supports.

134

However, as

of February 2022, four states have also used section 1115 demonstrations to waive NEMT, a benefit

that is typically required.

135

Section 1945 Health Homes: As of April 2021, there are 37 Health Home models across 21 states and

the District of Columbia, all of which must include comprehensive case management, individual and

family support, and referrals to community and social services, among other required services.

136

Managed Care Programs: As of 2018, 37 states have implemented requirements in their managed care

contracts related to HRSN and SDOH.

137

These requirements include:

o Relationships with social service providers (31 states);

_______________________

*

Section 1915(g) enables plans to provide case management services under Medicaid.

†

Section 1915(c) waivers allow states to pay for housing transition and tenancy services for beneficiaries to individuals meeting an

institutional level of care; Section 1915(i) benefits allow states to offer housing-related services for individuals who do not necessarily

meet an institutional level of care; Section 1915(k) benefits allow states to pay for services and supports identified as part of a person-

centered care plan, which can include home modifications or transition costs for moving an individual from an institution to a home or

community-based setting.

‡

Section 1115 demonstrations allow states to implement experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects that are likely to assist in

promoting the objectives of the Medicaid program.

April 2022 REPORT 12

o Inclusion of SDOH in care coordination (24 states);

o Social determinant screening (24 states);

o Dedicated staff for SDOH (17 states);

o SDOH quality performance measures (11 states);

o Provider training on SDOH (10 states);

o Collection and reporting on SDOH information (7 states);

o Value-added services related to SDOH (7 states);

o Member education on SDOH (5 states); and

o Social determinant expenditure requirements or incentives (3 states).

138

In addition to state flexibilities to address SDOH and HRSNs, CMS is partnering with the U.S. Department of

Agriculture to connect people enrolled in food assistance programs, such as SNAP, with Medicaid and vice

versa.

139

This partnership aims to improve participation rates and drive progress on both health and food

security.

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI): CMMI established the Accountable Health

Communities (AHC) Model in 28 locations to promote clinical-community collaboration to address HRSNs of

Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries through screening, referral, and community navigation services.

140

The

model, which focuses on five core HRSNs of housing instability, food insecurity, transportation problems, utility

difficulties, and interpersonal violence, found that 15 percent of the nearly 483,000 beneficiaries screened

were eligible for navigation services, and more than half of these navigation-eligible beneficiaries reported

more than one core HRSN.

141

CMMI is working to incorporate learnings from the AHC model into future

models. As part of their Strategy Refresh, CMMI will require all new models to collect and report on data on

HRSNs and SDOH, as appropriate.

142

In addition, CMS will consider models that aim to address upstream,

community-level SDOH.

Medicare: CMS is also working to address HRSNs and SDOH in the Medicare program. As of 2019, CMS

expanded the definition of supplemental benefits in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans to better address

SDOH.

143

As of 2019, MA plans can offer a broader array of benefits that are primarily health-related, such as

transportation, meal delivery, and adult day care, and as of 2020, plans can offer non-primarily health-related

benefits to the chronically ill, such as pest control.

144

In addition, Medicare ACOs provide high-quality care to

Medicare beneficiaries to ensure that patients get the right care at the right time through care coordination.

In FY22, CMS also included a request for information in the final Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment

System (IPPS) and Long-Term Care Hospital (LTCH) rule that sought ideas to make reporting of health

disparities based on social risk factors and race and ethnicity more comprehensive and actionable. Inclusion of

such measures in future payment rules would also build on the work of the CMMI AHC model.

145

Health Resources & Services Administration

Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) provides cooperative agreement funding for a number of

initiatives to support training and technical assistance for community health centers on topics related to SDOH

and HRSNs, including the Corporation for Supportive Housing (CSH) and the National Center for Medical-Legal

Partnerships.

146,147

CSH provides no-cost training and technical assistance to health centers that serve

individuals experiencing homelessness and/or operate Health Care for the Homeless programs. This assistance

provides health centers with strategies for improving health care access, housing stability, and health

outcomes for these patients.

148

The National Center for Medical-Legal Partnerships provides training and

April 2022 REPORT 13

technical assistance to health centers on implementing medical-legal partnerships. These partnerships bring

together legal professionals and health care teams to detect, address, and prevent social conditions negatively

impacting individual and community health. HRSA-funded health centers also play an important role in

improving HRSNs through the provision of enabling services, such as transportation, community health

workers, and other nonclinical services that enable people’s access to health care.

149

An important part of HHS’s strategic approach to addressing SDOH and HRSNs is to enhance data

infrastructure and how data is used. Aligned with this goal, as part of their Uniform Data System (UDS)

Modernization Initiative, HRSA began collecting SDOH data in 2020 and will gather patient-level data starting

in 2023, which will permit a better understanding of the impact of SDOH on clinical outcomes in health center

populations.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) seeks to protect public health through preparedness,

disease prevention, and health promotion. The focus of public health is on the health, safety, and well-being

of entire populations, and strives to provide the maximum benefit for the largest number of people.

150

Through their focus on public health, CDC’s data, research and programs address SDOH and HRSNs in a

number of ways.

Within the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, numerous programs focus

on SDOH and HRSNs. For example, for over 20 years, CDC’s Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community

Health (REACH) grants have funded locally-based, culturally-tailored solutions to addressing health inequities,

many of which are focused on SDOH.

151

Between 2014 and 2018, REACH provided better access to healthy

foods and beverages to over 2.9 million people, more opportunities to be physically active to approximately

1.4 million people, and access to local chronic disease programs linked to clinics for over 830,000 people.

152

In

2021, CDC also launched the Closing the Gap with Social Determinants of Health Accelerator Plans pilot project

that funds 20 state, local, tribal, or territorial jurisdictions to develop action plans including evidence-based

strategies to prevent and reduce chronic diseases among people experiencing health disparities.

153

In addition,

the Good Health and Wellness in Indian Country (GHWIC), CDC’s largest investment to improve American

Indian/Alaskan Native tribal health, focuses on improving nutrition, physical activity, and breastfeeding,

reducing commercial tobacco use and exposure, and strengthening links between community programs and

access to clinical services in order to promote health and prevent chronic disease.

Safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments are essential to children’s health and wellbeing. In

addition to reductions in chronic health conditions, preventing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) may also

lead to reductions in socioeconomic challenges.

154

CDC’s comprehensive approach to preventing ACEs uses

multiple strategies derived from the best available evidence.

CDC’s Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries (STEADI) initiative, offers tools for health care providers to

screen older patients for fall risk.

155

Components of STEADI include home modifications such as mounting grab

bars near toilets and installing carpet on all surfaces that may get wet, coupled with referral to effective

community-based fall prevention programs.

In August 2021, CDC launched the Community Health Workers for COVID Response and Resilient Communities

initiative to put additional trained CHWs in communities with high rates of COVID-19 and long-standing health

disparities related to race, income, geographic location, or other sociodemographic characteristics.

156

These

CHWs will help build and strengthen community resilience to fight COVID-19 by addressing health disparities.

April 2022 REPORT 14

The Health Impact in 5 Years (HI-5) initiative highlights non-clinical, community-wide approaches that have

evidence for reporting positive health impacts within five years.

157

The 14 evidence-based community-wide

population health interventions included in this initiative fall into two categories – those that “change the

context to make healthy choices easier,” and those that address the SDOH. The six interventions aimed at

addressing SDOH are:

Early Childhood Education

Clean Diesel Bus Fleets

Public Transportation System

Home Improvement Loans and Grants

Earned Income Tax Credits

Water Fluoridation

CDC has also established cross-departmental relationships aimed at addressing SDOH. CDC and the

Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) have established an interagency agreement to build a

sustainable, collaborative partnership to intentionally advance shared priorities related to health and housing.

The first step is to provide evidence informed approaches for affordable senior housing programs. CDC and

HUD are also working to develop a strategic framework or blueprint outlining goals to support state and local

public health agencies and housing agencies to partner and achieve shared priorities locally. In addition, the

Federal Transit Administration (FTA) in the Department of Transportation (DOT) has partnered with HHS,

including CDC, on the Interagency Coordinating Council on Access and Mobility (CCAM), which is charged with

increasing transportation access for low- income populations, older adults, and people with disabilities. The

CCAM is jointly working across 11 federal departments to develop a 2023-2026 Strategic Plan for Human

Services Transportation.

In addition to implementing and funding interventions aimed at impacting SDOH, CDC is also working to build

the evidence base around effective interventions. The Guide to Community Preventive Services (The

Community Guide), a collection of evidence-based findings of the Community Preventive Services Task Force

(CPSTF), is a resource to help jurisdictions select interventions to improve health and prevent disease in states,

communities, community organizations, businesses, health care organizations, or schools.

158

In 2020, CPSTF

selected SDOH as one of nine priority topics to guide their systematic reviews on population health

interventions for 2020-2025, and they formed a Health Equity Committee to assess and advance their work in

this area. In 2020, CDC also awarded funds to the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO)

and National Association of City and County Health Officials (NACCHO) to complete a retrospective evaluation

of multi-sector coalitions to advance health equity by addressing SDOH. Year one findings of the 42

community multi-sector partnerships from across the country selected as a part of the Improving Social

Determinants of Health–Getting Further Faster (GFF) pilot project showed that GFF partnerships built

community capacity to address SDOH through new or strengthened partnerships, data and data systems, or

strategic plans; leveraged resources; or engaged residents.

159

Ninety percent of GFF partnerships contributed

to community changes that promote healthy living, such as building new walking trails, bike lanes, and

playgrounds; creating new community and school gardens; and adopting tobacco-free policies. More than half

of GFF partnerships reported positive health outcomes data for their SDOH initiatives, including improved

health behaviors, clinical outcomes, and overall health and wellness, and decreased health care use and costs.

Administration for Community Living

The Administration for Community Living (ACL), in partnership with CMS, the Substance Abuse and Mental

Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), ASPE, and HUD, recently launched the Housing Services Resource

Center, which fosters collaboration and cross-sector partnerships to streamline services, better leverage

resources, and make community living possible for more people.

160

This initiative offers innovative models and

strategies to people who work at the organizations and systems that provide housing resources and

April 2022 REPORT 15

homelessness services, behavioral health services, independent living services and other supportive services,

and others who are working to help people live successfully and stably in the community. It provides

resources on how to develop and expand partnerships, tools for community collaborations, and information

on supporting people with disabilities, older adults, and people experiencing homelessness to get and/or keep

affordable and accessible housing and voluntary supportive services.

ACL also funds a nationwide network of aging and disability organizations that provide access to a variety of

local community-based services that address social needs. Through this network, ACL provides 150 million

home-delivered meals to over 883,000 individuals and 73.6 million congregate meals to more than 1.5 million

seniors, funded through the OAA Nutrition Program.

161

Nutrition services help older Americans remain healthy

and independent in their communities by providing meals and related services in a variety of community

settings and via home-delivery to older adults who are homebound due to illness, disability, or geographic

isolation. As compared to the U.S. population age 60 and older, participants in the OAA Nutrition Program are

more likely to be in poor or fair health, have difficulties with three or more ADLs, live alone, and live in rural

communities.

162

In addition to meals, the program provides nutrition screening, assessment, education, and

counseling, and provides connections to other in-home and community supports. ACL also provides

transportation services through their network, providing more than 20.4 million rides to doctor’s offices,

grocery stores, pharmacies, senior centers, meal sites, and other critical daily activities.

163

Forty-six percent of

passengers on OAA-funded transportation are mobility impaired, meaning they do not own a car, or if they do

own a car, they do not drive, and are not near public transportation.

164

Of the transportation participants, 71

percent have at least one chronic condition that could impair their ability to navigate safely, and 96 percent

take daily medications, with over 16 percent taking 10 to 25 medications daily. In addition, ACL’s network

provided 3.3 million hours of case management services in Fiscal Year 2019 to assess needs, develop care

plans, and arrange services for older persons or their caregivers. Over 82 percent of clients receiving case

management reported that, as a result of the services arranged by the case manager, they were better able to

care for themselves.

165

In addition, ACL’s Social Care Referrals Challenge is working to support health care systems and community-

based organizations through health IT solutions.

166

The challenge seeks to cultivate care coordination,

including the sharing of standardized data on SDOH, by developing or optimizing interoperable, scalable

technology solutions that foster connections between community-based organizations and health care

systems. Twelve proposals were selected for phase two of the competition, which will give the teams $30,000

and will allow teams to continue develop their solutions as they compete for a second award of $60,000 and a

grand prize of $140,000.

Through grant awards made in September 2021, ACL is also supporting the infrastructure of 12 Network Lead

Entities, or community hubs, that coordinate the activities of a broader network to efficiently contract with

health plans and providers to address social needs. Increasingly, CBOs are organizing to form networks,

allowing them to deliver a broad scope of services, expand populations served and geographic coverage, build

stronger administrative functions, and offer a single point of contracting for payers.

167

As part of their support for their disability network, ACL also offers several grants to enhance the cultural and

linguistic competency of the disability network to ensure that all people with disabilities can access ACL-funded

programs and services.

168

These include grants to build cultural competency within University Centers for

Excellence in Developmental Disabilities, increase the diversity of leadership and staff in the development

disability network, establish a diversity community of practice to create and share policies, practices, and

systems in cultural and linguistic competence in disability programs, and conduct a gap analysis of cultural

competency in the developmental disability network programs, among others.

Administration for Children and Families

April 2022 REPORT 16

The Administration for Children and Families (ACF) promotes the economic and social well-being of families,

children, youth, individuals, and communities. Although not specifically designed to influence health, these

anti-poverty and family support programs provide cash assistance, in-kind family support, and other individual,

family and child services that can profoundly affect traditional health outcomes. All ACF programs, including

childcare, Head Start, Child Support Enforcement, Child Welfare, Runaway and Homeless Youth, Temporary

Assistance for Needy Families, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood programs, community services,

refugee resettlement, Low Income Home Energy Assistance, adolescent pregnancy prevention, and family

violence prevention, address social determinants that can affect health and quality of life outcomes.

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance benefits, which supported more than one

million families in 2019 experiencing poverty, reduced poverty by 11.3 percentage points among

recipients.

169,170

TANF funds are used to supplement income and for employment, education, and training that

can promote economic mobility; to provide transportation assistance; to provide subsidies for utility payments

to prevent utility shut offs; and to provide subsidies for food assistance. Case management provided through

TANF can also screen for and identify health-related barriers such as mental health concerns or substance use

disorder. During the COVID-19 pandemic, TANF programs across the country also used TANF funds to serve

and support families experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

171

HHS oversees the national Child Support program, partnering with state, tribal and local child support

agencies, and others to encourage parental responsibility so that children receive financial, emotional, and

medical support from both parents, even when they live in separate households. Child support payments help

to increase income and reduce poverty among low-income custodial parents and their children. In fiscal year

2020, preliminary data shows the national program collected $34.9 billion and served 13.8 million children and

their families.

172

Additional analyses shows that child support reduced poverty by 6.3 percentage points

among individuals in families who received payments.

173

ACF also provides grant funding and oversight to the programs that provide Head Start services across the

country. Head Start promotes school readiness by offering educational, nutritional, health, social, and other

services to children in low-income families.

174

In 2019, Head Start was funded to serve nearly one million

children and pregnant women, and since its inception it has served more than 37 million children and their

families.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) provides programs and resources

to help address social determinants of behavioral health, SDOH, and HRSNs for individuals with behavioral

health conditions. For example, services provided through SAMHSA’s grant programs help people with mental

and substance use issues find housing and supportive services, increase access to disability income benefits for

eligible adults who are experiencing or at risk for homelessness, and provide case management and other

supports that assist in preventing or ending homelessness.

175

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) seeks to improve the health

and well-being of individuals and communities through the use of technology and health information,

including SDOH information, that is accessible when and where it matters most. Advancing the use and

interoperability of SDOH data is important to improving the health and well-being of all individuals and

communities. Though not discussed in the evidence-based interventions above, accessible data is

fundamental to the success of SDOH interventions. ONC is focused on ensuring that both patients and

providers understand what capabilities are possible and required by the 21st Century Cures Act to ensure that

with increased adoption of health information technology (IT), we can also more effectively capture

April 2022 REPORT 17

information about the conditions in which people live, learn, work, and play to improve health outcomes.

Standardization of the way in which the data is obtained and exchanged will help providers more easily

address non-clinical factors, such as food, housing, and transportation insecurities, which can have a profound

impact on a person’s overall health. For example, as of March 2022, almost all hospitals and roughly 75

percent of physicians use electronic health records (EHRs) certified through the ONC Health IT Certification

Program, helping to enable widespread capabilities for the capture, reporting, exchange, and use of granular

race and ethnicity data. This functionality will soon extend to the widespread use of interoperable SDOH data

that can be electronically captured, used, and exchanged.

ONC works collaboratively with federal partners and the stakeholder community to advance the electronic

exchange and use of SDOH data to help improve individual and population health by guiding the development,

dissemination, and adoption of health IT standards; informing the development of policies to overcome SDOH

data interoperability challenges and data use; supporting states and local governments as they build the

infrastructures for SDOH data; and driving innovation in care delivery by using health IT tools and standards to

integrate SDOH data into workflows.

CONCLUSION

Studies indicate that some SDOH and HRSN interventions, provided in the right settings and depending on the

population, can improve health outcomes and well-being. In addition, some interventions may also decrease

health care costs, though successful interventions can be cost-effective and worth undertaking even if they do

not ultimately save money overall. Much of the research to date has focused on shorter-term outcomes and

medically complex populations or those with high health care utilization. Research on community

interventions has also demonstrated health improvements with long-term impact. However, as we focus our

efforts on SDOH and HRSNs, more work to assess the impact of various interventions on multiple populations

is warranted. Additional research can help us better understand how interventions to address risks related to

SDOH and HRSNs in less medically complex individuals impact health and well-being over the life course, as

well as the longer-term impacts of interventions; the impact on a wider range of populations, including rural

communities and individuals without chronic illnesses; and the most appropriate “dose” of various

interventions. Further, as discussed in the introduction, additional research is needed that focuses on health

outcomes, in addition to health utilization, health costs, and healthy behaviors.

In addition to efforts to improve SDOH and HRSNs, HHS is committed to building the evidence base and

measuring success related to these efforts. The Healthy People initiative identifies data-driven national

objectives to improve the health of the nation. One of Healthy People 2030’s five overarching goals is

specifically related to SDOH: “Create social, physical, and economic environments that promote attaining the

full potential for health and well-being for all.”

176

The benchmarks set by Healthy People 2030 include targets

to monitor progress and motivate and focus action and will help HHS in its efforts to track progress on

improving SDOH.

Through a whole-of-government, multi-sector strategy, HHS is working to improve health and well-being of the

U.S. population by investing in efforts to identify and address the underlying systemic and environmental

factors that affect health status. As discussed further in “HHS’s Strategic Approach to Addressing Social

Determinants of Health to Advance Health Equity – At a Glance,

*

” HHS will drive progress through coordinated

strategies and activities to better integrate health and human services and to advance public health initiatives

involving cross-sector partnerships and community engagement to address specific SDOH drivers. These

strategies and activities include strengthening data and data infrastructure, which can be used to improve

evaluation and support other objectives moving forward; improving connections between health and social

_______________________

*

https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/aabf48cbd391be21e5186eeae728ccd7/SDOH-Action-Plan-At-a-Glance.pdf

April 2022 REPORT 18

services, including community partners, to address HRSNs; and adopting whole-of-government collaborations

to address SDOH and enhance population health and well-being. HHS is not only supporting and implementing

initiatives that are based on existing evidence but is also working to evaluate current efforts to contribute to

our understanding of effective SDOH and HRSN interventions, refine existing efforts, and identify future

initiatives to address HRSNs and SDOH that may also have a beneficial effect on health and well-being.

April 2022 REPORT 19

REFERENCES

1. Ely DM, Driscoll AK. Infant Mortality in the United States, 2018: Data from the Period Linked

Birth/Infant Death File. National Vital Statistics Report; vol 69 no 7. Hyattsville, MD: National Center

for Health Statistics. July 2020.

2. Ely DM, Driscoll AK, Matthews TJ. Infant Mortality Rates in Rural and Urban Areas in the United

States, 2014. NCHS Data Brief; no 285. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

September 2017.

3. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Disparities. November 17, 2020. https://www.cancer.gov/about-

cancer/understanding/disparities

4. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States Spotlight: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in

Heart Disease. April 2019.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/spotlight/HeartDiseaseSpotlight_2019_0404.pdf

5. Schopfer DW. Rural health disparities in chronic heart disease. Prev Med. 2021 Nov;152(Pt 2):106782.

doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106782. Epub 2021 Sep 7. PMID: 34499971.

6. Arias E, Tejada-Vera B, Ahmad F, Kochanek KD. Provisional life expectancy estimates for 2020. Vital

Statistics Rapid Release; no 15. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. July 2021.

7. Henning Smith, C., A.M. Hernandez, M. Ramirez, R. Hardeman, K. Kozhimannil. March 2019. “Dying

Too Soon: County-Level Disparities in Premature Death by Rurality, Race, and Ethnicity.” University of

Minnesota Rural Health Research Center https://3pea7g1qp8f3t9ooe3z3npx1-wpengine.netdna-

ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/1552267547UMNpolicybriefPrematureDeath.pdf

8. Krehely J. How to Close the LGBT Health Disparities Gap. Center for American Progress. December

2009. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/how-to-close-the-lgbt-health-disparities-gap/

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Development and Disability, Health Equity.

January 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/humandevelopment/health-equity.html