A

MEDLEY

OF

PRACTICE APPROACHES

Social Work Assessment:

Case Theory Construction

by Cynthia

D.

Bisman

Abstract

To

intervene effectively, social workers need to make sense

of

clients and their situations.

A

case theory approach to assessment pro-

vides a framework to

formulate

assessments that are clear and directly

related

to the real-world problems clients present Explaining

the problem situation,

case

theory

forms

the foundation for

selection

of

intervention

strategies

and methods to achieve change. Build-

ing case theory requires practitioner abilities to

form

concepts,

relate

concepts

into

propositions,

develop hypotheses, and organize

these into a coherent whole. Including

case

background information,

observations

and relevant professional literature,

case

theory pre-

sents an accurate and cogent comprehension

of

the client

Two

case

examples

of

depression illustrate the important relationship

among concepts, empirical referents, propositions, general theorles, and intervention, highlighting how case theory guides practice.

AN OVERARCHING INQUIRY DIRECTS this article:

How do social workers figure out what is going

on

with

clients? Embedded within is another question: What is

the point of this knowledge?

I

offer here a case theory

framework for use by social workers to make sense

of

cli-

ents and their situations and connect that comprehension

to treatment planning and intervention.

In social work, it is the assessment that determines

the nature of the client’s current situation at a particular

point in time. Resulting in the product

of

a written as-

sessment (variously called a psychosocial study, intake re-

port, or social history, among other nomenclature) and

entailing specific tasks such as observing and interview-

ing clients along with data gathering, the process of as-

sessing is often ignored. Yet, without a clear framework

for thinking about and engaging in the process of assess-

ment, the products will be flawed and either useless to

the social worker, or harmful to the client, or both.

Through gathering data that determines the relevant

attributes of each case, social work assessment provides

the “here and now” and how

it

got that way. A far more

complex and significant process than data collection, as-

sessment also incorporates the tasks of deciding which

data to seek and how to organize it. Moreover, all prac-

tice components flow from the assessment that shapes

the character of the professional relationship, impacts

on

communication methods and skills, directs social work

intervention, determines measurements and data collec-

tion needs, and guides evaluation. As a joint activity by

both the social worker and the client, assessment requires

their mutual understanding and agreement. Engaged in a

journey together, social workers and clients work

to

de-

termine the nature

of

the problem causing the client dif-

ficulty

so

that they can change the situation.

Assessment was an effort by Mary Richmond to

make the social work profession more scientific.

In

her

Social

Diagnosis

(1917), she provides a lengthy and de-

tailed method for obtaining social evidence, which was

used by the social worker for understanding the client’s

difficulties and deciding “what course

of

procedure” to

follow (p. 39). She states, “social diagnosis is the attempt

to arrive at as exact a definition as possible

of

the social

situation and personality

of

a given client. The gathering

of evidence, or investigation, begins the process, the crit-

ical examination and comparison

of

evidence follows,

and last come its interpretation and the definition of the

social difficulty” (p.

62).

Social work has not yet reached a consensus on the

structure and function of assessment. Some in the profes-

sion criticize a current trend

to

substitute psychodiagno-

sis for social work assessment by relying

on

prepackaged

scales such as the

DSM-IV

(Mattaini

&

Kirk, 1993; Ab-

bott, 1988; Ikver

&

Sze, 1987). Others, like Hudson

(1990),

call for heavy reliance

on

computers and stan-

Families in Society: The Journal

of

Contemporary Human Services

Copyright

1999

Families International, Inc.

240

Bisman Case

Theory

Construction

dardized scales, and Hopton (1998) reports on the use of

psychological profiles in risk assessments.

Importance

of

a Case

Theory

Approach

to

Assessment

For social work assessments that are clear and directly

related to the real-world problems that clients present, case

theory provides a means

of

conceptualizing assessment and

formulating assessments that are not only accurate and in-

formative but also lead directly

to

relevant interventions.

Case theory provides a set

of

ideas to understand and treat

the symptoms or problems in functioning of one particular

client (client may refer to an individual, family, group, com-

munity, or organization).

Consider the following situation facing Melissa, a social

worker employed for

two

years by a child guidance center.

The eight-year-old client, Edith, is in second

grade and has been residing with her maternal

grandmother for the past year along with her

ten-year-old sister and two older male cousins.

Edith cries often, is uncommunicative at home,

picks fights with children at school, and does

poorly in school work. Records show that

Edith’s mother abused drugs and had several

abusive relationships. Edith does not know her

father, who is incarcerated.

How does Melissa understand these facts? She looks

closely at Edith’s sad face and remembers information

from her classes about attachment theory (Bowlby, 1977)

that discontinuities of parenting can result in depression.

Melissa has always been drawn to object relations theo-

ry (Winnicott, 1989), which offers her a way of under-

standing Edith’s problems. Melissa decides that Edith has

poor social relations with others because her split be-

tween good and bad was not resolved before she reached

one year old and because of that she has low self-esteem

resulting from lack of a supportive caregiver during in-

fancy. Deciding that Edith is depressed, Melissa recom-

mends weekly therapy sessions to help increase her self-

esteem, utilizing play and supportive group therapy.

What

do

we think of Melissa’s approach to this case

and how she came to an understanding about Edith?

Some may worry that Melissa was too quick with her di-

agnosis

of

depression, possibly neglecting other explana-

tions for Edith’s problematic behaviors. What

if,

instead

of struggling with issues in her past, Edith is being

abused now, possibly

by

her older male cousins? Or per-

haps her symptoms are the result of her mother’s drug

use during pregnancy? Most of us can probably agree

that Melissa needs a fuller understanding to be sure she

is

on

the right track. More information is necessary

about Edith’s current home environment along with a

learning assessment from the school and a current medi-

cal examination. If Edith is currently residing in an abu-

sive situation, she continues

to

be at risk without inter-

vention aimed at providing her with a safe environment.

Likewise, should Edith have physiological problems

making learning difficult for her, targeted help from the

school at this early age could prove highly productive.

Missing in Melissa’s assessment and intervention is a

deliberative process of building an understanding that ac-

curately explains her client’s symptoms.

A

case theory

approach to assessment provides a structure for social

workers to follow in comprehending their clients. This

framework emphasizes utilization of relevant contempo-

rary literature and direct focus

on

the empirical evidence

in

the client’s life. Conceptualizing assessment as case

theory building enables practitioners to articulate what is

happening with a particular client at one specific point in

time and is essential to an intervention that is germane to

that client and relevant to the presenting problem and

context of the client situation.

Building case theory demands the knowledge about

concepts and theory construction and the skills

to

relate

concepts into propositions, develop hypotheses, and

avoid deductive and inductive fallacies. Let us review

these terms and then illustrate their use in formulating a

case theory.

Theory

As

Bisman and Hardcastle (1999) explain, pursuit of

theory

is

to provide orderly explanations of the confu-

sions in life experiences. In drawing patterns from obser-

vations to explain phenomena, different persons may ex-

plain the same events with a range

of

theories. The theory

is not real but rather is the individual’s attempt to explain

real things. They further emphasize that available tech-

nologies and contemporary ideologies influence theories

by discussing the contrast in theories about depression

from the 1970s with those in the 1990s. Freudianism

dominated the 1970s explaining depression

as

a primar-

ily psychological phenomenon. In the 1990s pharmacol-

ogy is the mode, viewing depression as a bio-chemical

imbalance while gene research offers new ways

to

under-

stand and explain the etiology

of

what was once consid-

ered solely a “mental” disorder. They predict more rapid

FAMILIES

IN

SOCIETY

May

-

June

7999

T&?

idea:

Labt.l:

The

IIlentdl

The

word

or

picture

and words represent-

Lonwwmm

ot

ing

the

idea.

\\

orld.

\otllt‘

pdrt

ot

[he

shifts with increasing advances in technological knowl-

edge.’

Constructions by individuals to order events, theories

offer logical conclusions based on presented relationships.

Other than final proofs of logic and mathematics, which

stem from stated premises and are not from or about the

empirical world, theories do not offer universal laws bur

rather present different levels

of

abstractness (some, such

as Lakoff and Nunez, 1997, believe that even abstract

mathematical concepts are based on human experience).

Perhaps one

of

the more elegant definitions of theo-

ries is offered by Karl Popper (1982) when he refers to

“theories as human inventions

-

nets designed by

us

to

catch the world” (p.

42),

warning that “there is no ahso-

lute measure for the degree

of

approximation achieved

-

for the coarseness or fineness of the net”

(p.

47).

Whether grand, scientific, or case, theory

is

a sys-

tematically related set

of

propositions that explain and/or

predict phenomena (Dubin, 1978,

pp.

15-32; Lewis,

1982, pp. 18,

61-63;

Reynolds, 1971,

pp.

10-11,

87-

1

14).

While theories are not inherently “real” or “hypo-

thetical,” their usefulness as constructions increase the

more they can explain and predict. Theories range

through levels

of

abstractness from grand theories that

explain a lot

of

phenomenon

to

very concrete and cir-

cumstantial case theories that are locked in a specific

time, place, and event. Freudian theory offers explana-

tion

of

all human development and behavior and

is

an

example of a grand theory. Good case theory provides

understanding

of

the case, explaining why a particular

client is behaving in a certain manner, laying the foundci-

tion for prediction of interventions necessary

to

accom-

plish the case objectives and case change.

%e

&h€:

The thing

in

the

world

captured

by

the idea.

Concept Formation

Case theory building requires specification and de-

velopment

of

concepts

-

the fundamental units and

building blocks

of

propositions and theories. For practi-

tioners

to

understand the meaning

ot

case theory, they

must understand the theory’s concepts. Ideas in the

mind.

concepts are the words or labels symbolizing the external

things that the ideas represent. Just as we discussed with

theories, concepts are not reality but represent a mental

construction

of

realit!..’

The mental and empirical processes of developing

and operationalizing concepts and relating the concepts

to

explain and predict things is theory building. I’racti-

tioners must relate concepts in case theory to each other.

It

the case theory building is faulty, interventions based

on

the theory are not likely

to

produce the intended re-

sults and may result in harm.

I

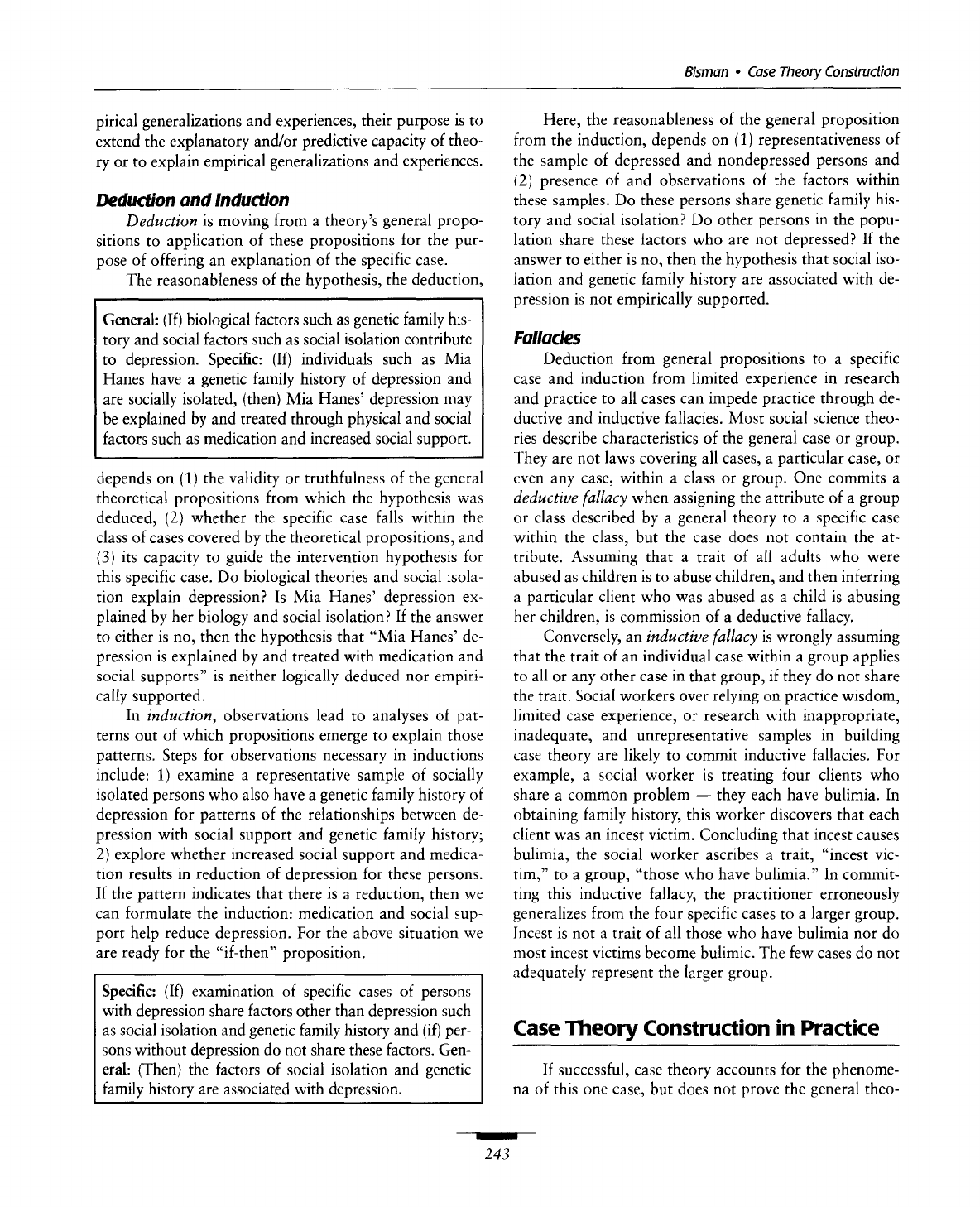

Jnderstanding

concept

starts with three components

illustrated in Table

1

below:

I.

The idea or mental image and construction in the

2.

The words or labels symbolizing the idea, and

3.

The external thing, phenomena, and empirical refer-

ents in the world represented by the labels.

mind.

Table

1.

I

Child abuse

1

I

!

Conceptualization is the process

of

assigning words

to ideas, abstractions, and constructions

of

empirical re-

slit!-

that have empirical references. Practitioners must

not reify the concept by assuming that the idea is real or

the only construction

of

reality. It is also important

to

de-

\,rlop the nominal detinition and domain

of

the concept

tu

distinguish empirical referents that fall within the idea

trom those that do not. Operational definitions that cap-

rurc the idea are prerequisite

to

concepts that are usable

in

c~se theory.

Propositions and Hypotheses

Theories are composed

of

propositions,

which are

statements about the relationships among elements, con-

cepts, or attributes

of

one or more concepts. Propositions

allow

us

to understand concepts and relate and integrate

them into theory. The task in building and reviewing the-

ory. including case theory,

is

to

find the “if-then’’ propo-

<itions that constitute the theorv to explain the case and

provide prediction

for

the appropriate intervention.

Hypotheses

are propositions that are capable of em-

pirical testing but as yet are untested. One function

of

re-

Fearch is to test and establish the validity of hypothetical

propositions. Deduced from theorv or induced from em-

‘

The

following

sections

ovi

theory draw

from

Bismm and

Wilrdc-astle,

1999.

chapter

four.

‘Blumer’s

(1

969)

iiwk

OIZ

symbolic interactionism influences

thesc

ideas.

Bisman Case Theory Construction

pirical generalizations and experiences, their purpose is to

extend the explanatory and/or predictive capacity of theo-

ry or to explain empirical generalizations and experiences.

Deduction and Induction

Deduction

is moving from a theory’s general propo-

sitions to application of these propositions for the pur-

pose of offering an explanation of the specific case.

The reasonableness of the hypothesis, the deduction,

General: (If) biological factors such as genetic family his-

tory and social factors such as social isolation contribute

to depression. Specific: (If) individuals such as Mia

Hanes have a genetic family history of depression and

are socially isolated, (then) Mia Hanes’ depression may

be explained by and treated through physical and social

factors such as medication and increased social support.

depends on

(1)

the validity or truthfulness of the general

theoretical propositions from which the hypothesis was

deduced,

(2)

whether the specific case falls within the

class

of

cases covered by the theoretical propositions, and

(3)

its capacity to guide the intervention hypothesis for

this specific case.

Do

biological theories and social isola-

tion explain depression?

Is

Mia Hanes’ depression ex-

plained by her biology and social isolation? If the answer

to either is no, then the hypothesis that “Mia Hanes’ de-

pression is explained by and treated with medication and

social supports” is neither logically deduced nor empiri-

cally supported.

In

induction,

observations lead to analyses of pat-

terns out of which propositions emerge to explain those

patterns. Steps for observations necessary in inductions

include:

1)

examine a representative sample of socially

isolated persons who also have a genetic family history of

depression for patterns of the relationships between de-

pression with social support and genetic family history;

2)

explore whether increased social support and medica-

tion results in reduction of depression for these persons.

If the pattern indicates that there is a reduction, then we

can formulate the induction: medication and social sup-

port help reduce depression. For the above situation we

are ready for the “if-then’’ proposition.

Specific: (If) examination of specific cases of persons

with depression share factors other than depression such

as social isolation and genetic family history and

(if)

per-

sons without depression do not share these factors. Gen-

eral: (Then) the factors of social isolation and genetic

family history are associated with depression.

Here, the reasonableness

of

the general proposition

from the induction, depends on

(1)

representativeness of

the sample

of

depressed and nondepressed persons and

(2)

presence of and observations of the factors within

these samples. Do these persons share genetic family his-

tory and social isolation?

Do

other persons in the popu-

lation share these factors who are not depressed? If the

answer to either is no, then the hypothesis that social iso-

lation and genetic family history are associated with de-

pression is not empirically supported.

Fallacies

Deduction from general propositions to a specific

case and induction from limited experience in research

and practice to all cases can impede practice through de-

ductive and inductive fallacies. Most social science theo-

ries describe characteristics of the general case or group.

They are not laws covering all cases, a particular case, or

even any case, within a class or group. One commits a

deductive

fallacy

when assigning the attribute of a group

or class described by a general theory to a specific case

within the class, but the case does not contain the at-

tribute. Assuming that a trait of all adults who were

abused as children is to abuse children, and then inferring

a particular client who was abused as a child is abusing

her children, is commission of a deductive fallacy.

Conversely, an

inductive

fallacy

is wrongly assuming

that the trait of an individual case within a group applies

to all or any other case in that group,

if

they do not share

the trait. Social workers over relying on practice wisdom,

limited case experience, or research with inappropriate,

inadequate, and unrepresentative samples in building

case theory are likely to commit inductive fallacies.

For

example, a social worker is treating four clients who

share a common problem

-

they each have bulimia. In

obtaining family history, this worker discovers that each

client was an incest victim. Concluding that incest causes

bulimia, the social worker ascribes a trait, “incest vic-

tim,” to a group, “those who have bulimia.” In commit-

ting this inductive fallacy, the practitioner erroneously

generalizes from the four specific cases

to

a larger group.

Incest is not a trait of all those who have bulimia nor do

most incest victims become bulimic. The few cases do not

adequately represent the larger group.

Case

Theory

Construction in Practice

If

successful, case theory accounts for the phenome-

na of this one case, but does not prove the general theo-

I

243

FAMILIES

IN

SOCIETY

May

-

June

7999

ry for classes of persons. A construction of social reality,

case theory is the meaning attached by the social worker

to

the client’s narrative and other gathered information,

leading to shared construction

of

a new reality for the cli-

ent, reflected in the intervention.

General and Case

Theories

Practice without case theory leaves practitioners rely-

ing

on

the general theories of behavior, which are usually

too broad to be of much use in adequately understanding

a specific client

or

are dependent

on

loosely formed

hunches that may relate more to their own instincts than

to empirical data. Faulty case theories are also harmful.

Drawing from the wrong general theories, they provide

information that is not relevant and may even be danger-

ous

to the client.

Social, psychological, and behavioral theories includ-

ing systems and exchange theory, psychodynamic, oper-

ant, social learning, and cognitive theories do inform case

theories. Nevertheless, they are quite different. These con-

ceptual models are nomothetic, which means they apply

to groups

of

persons while case theories are idiographic.

As Bisman states,

“By

definition,

if

the case theory fits this

individual case,

it

will

totally

fit

no

other client situation”

(1994,

p.

117).

A central feature of case theories is their

use of these general theories to provide support from a

wide body of professional research and scholarship.

Case theory determines which

of

these general theo-

ries or professional literature to choose. Rather than one

particular theoretical model driving all practice decisions,

a case theory approach requires knowledge

of

multiple

theories and the ability to utilize a framework that best re-

lates to the circumstances

of

a specific client. This may be

clearer when we think of a medical situation. We would

not expect a specialist in gastrointestinal disorders

to

di-

agnose all problems as intestinal, but rather to rely

on

a

thorough medical examination and remain open to a

range

of

explanations for the patient’s problems. Prescrib-

ing medication for pain resulting from gastro reflux can

result in great (even deadly) harm if the patient’s pain is

instead from angina and heart attacks

go

untreated.

Furthermore, for fully developed and valid social

work case theories that adequately address the breadth

of

the social work domain, social workers need

to

use

bio-

psycho-social models, including biological information of

genetic content and physical attributes, psychological

data covering the intrapsychic and personality factors,

and the social information about range and type of com-

munity and social supports and resources with their avail-

ability to the client.

These differ from the

(1)

bio-psycho-medical theories

of human behavior that present behavior as the result of

the individual’s biological and intrapsychic content,

whether due to genetic content or early socialization,

(2)

educational theories that view behavior and management

of social relations and the social environment as learned

or conditioned, and

(3)

psycho-social theories that inter-

pret behavior as a function

of

the individual’s psycholog-

ical content in interaction with the social context.

It is not unusual, however, for practitioners to skip

the process of formulating such an understanding for each

of their clients and instead solely rely

on

general concepts,

such as depression or alcoholism. A basic assumption,

however, in utilization of diagnostic categories is a shared

understanding of these phenomena. Yet as we discussed

earlier, these concepts are not real but rather refer to em-

pirical events. Accordingly, knowledge of these specific

circumstances is necessary

to

understand each individual

client’s depression or substance abuse in order

to

plan an

intervention that relates to that particular client’s real-life

circumstances. This is particularly important because

there are many general theories explanatory

of

concepts

such as depression and alcohol abuse. Moreover, with in-

creasing reliance on the growing number of DSM

IV

cat-

egories,

it

is essential to clarify the meaning

of

the diag-

nosis. Just as physicians must provide specificity when

diagnosing cancer or heart disease, social workers must

identify the attributes of their diagnoses.

Case Example

and

Case

Theory

Let

us

consider another example and examine the

so-

cial worker’s approach

to

building a case theory.

Based at an urban community mental health center

which provides services

to

any residents, the social work-

er, Janet, meets with Rosie, a forty-five-year-old Latino

woman. Currently unemployed, Rosie completed tenth

grade and has held various jobs, usually as a sales clerk.

She lives with her twenty-five-year-old daughter, has lit-

tle interaction with her family, and keeps very few

friends. Rosie came into the session complaining that she

feels sad and has little energy. When Janet pushes for

specificity, she learns that Rosie often sits around the

house all day doing nothing, sleeps about twelve to four-

teen hours, watches

TV

about six

to

eight hours, and

is

losing weight because she does not eat very much. Janet

asks how

long

she has felt this way and learns that Rosie

has had these bad feelings

on

and off since her early

teens, when she used

to

think

of

killing herself. These

thoughts often alternated with great bursts of energy

when Rosie felt wonderful. Asking how it is that she is

I

244

Bisman

Case

Theory

Construction

now asking for help, she learns Rosie feels worse since

testing positive for

HIV,

three months ago.

Janet formulates the following case theory:

Rosie’s recent

HIV

diagnosis is exacerbating

her

long

term social isolation and possible clini-

cal depression. Goldstein (1995) and Jue

(1

994), indicate that stigma from

AIDS

often

socially isolates these patients, while Mancoske

(1

996) points to their greater risk of suicide.

In-

dividuals need an active energy exchange with

others as Greene

(1

991) explains in her discus-

sion of systems theory, and for a long time Rosie

has had

no

person with whom she can talk

openly. Her long history of severe

mood

swings

suggests bipolar disorder. Evidence supports a

biological basis

for

treatment of depression

(Sperry, 199.5). Jensen

(1

994) points to

a

psy-

chosocial perspective combined with

a

biologi-

cal perspective.

Because she knows we can use the concept

of

depres-

sion

to

describe different conditions, Janet identifies the

empirical indicators relevant for each client labeled as de-

pressed. The empirical behaviors for Rosie include the

following problems: sleeps an average

of

thirteen hours

per day, shows a decrease in appetite, has severe mood

swings, and an overall lack of functioning with extensive

Developed from data collection and

observations, case theory presents social

workers’ understanding

of

a particular

client‘s problematic condition at a

specific point

in

time.

periods of sitting around and watching television.

Propositions in Janet’s case theory pose a

relationship between social isolation, illness, biology, and

depression. Janet’s hypothesis is a deduction that Rosie’s

symptoms are explained by her biology, social isolation,

and disease. Correspondingly, Janet refers to general the-

ories of systems, biological and psychological, and social

explanations for understanding depression and the psy-

chosocial effects of

AIDS.

Emerging from this case theory, Janet’s intervention in-

cludes both increasing social supports and a medical con-

sult to consider pharmacology for the possible bipolar

disorder. Focus on just AIDS, or only the social isolation,

or solely the clinical depression ignores important vari-

ables. Janet is aware that any of these narrow interven-

tions is potentially harmful to Rosie.

When we compare Janet’s approach to understand-

ing Rosie with our earlier example of Melissa, we can see

the enhanced practice by Janet who is able to directly link

this understanding to her intervention based on concrete

evidence. The clear statement of her case theory’s propo-

sitions and hypotheses and identification of the general

theories she uses prevent fallacies in her thinking.

By

broadly basing her case theory to incorporate multiple

hypotheses, she logically draws from a range

of

general

theories resulting in a plan of intervention that addresses

the breadth of social work practice by including biologi-

cal,

psychological, and social factors.

Summary

In response to the initial questions of how social

workers make sense of clients and what they do with that

information, we have examined a case theory approach

to social work assessment requiring comprehension of

theory, specification of concepts, and development of

propositions and hypotheses. Emphasis is on the linkages

between building a theory of the case with accurate client

assessments and relevant subsequent practice interven-

tions. While recognizing the importance

of

case theory

constructions

by

practitioners, this framework also dis-

tinguishes case theory from those general theories found

in the literature.

Case theory, like all theory, is explanation of phe-

nomena. Idiographic, case theory applies only to a spe-

cific case and is distinct from social and behavioral theo-

ries, which are nomothetic and apply generally to groups

of persons. Developed from data collection and observa-

tions, case theory presents social workers’ understanding

of a particular client’s problematic condition at a specif-

ic point in time.

As

Florence Hollis

(1970)

stressed in her

development of the psychosocial approach, the purpose

of assessment is to develop the basis for treating each cli-

ent as a separate individual. Addressing specific empirical

events, the test

of

the case theory is the extent to which

it

explains this unique client, accounts for the phenomena,

and guides a successful intervention. Case theory con-

nects this client’s past to the present and future in order

I

245

FAMILIES

IN

SOCIETY

May-June

7999

to project a future set of events

-

the change in the cli-

ent’s presenting problems (Bisman,

1994).

Social workers must consider and confront both

social context and individual content of behavior and ac-

cordingly rely

on

bio-psycho-social theories where

behavior is a function

of

the individual client’s biological

and psychological content and the social context

-

the

social work domain.

Social work practice involves using and testing theo-

ries.

To

formulate their assessments, social work practi-

tioners require theory-building knowledge and skills.

Building case theory requires practitioner abilities to

form concepts, relate concepts into propositions, develop

hypotheses, and organize these into

a

coherent whole.

From case theory’s coherent explanation

of

the empirical

referents and reference to general theories and wide pro-

fessional knowledge, come selection of intervention

strategies with methods to change the presenting prob-

lems. Including client background information and perti-

nent professional literature, case theory presents a cogent

and valid comprehension of the client, a prerequisite for

appropriate interventions that are helpful to clients.

Jensen,

C.

(1994). Psychosocial treatment

of

depression in women:

Nine single-subject evaluations.

Research

on

Social Work Prac-

tice,

4,

267-282.

Jue,

S.

(1994). Psychosocial issues

of

AIDS

long-term survivors.

Fami-

lies in Society,

75(6), 324-332.

Lakoff,

G.,

&

Nunez, R. (1997).

In

L. English (Ed.),

Mathematical rea-

soning: Analogies, metaphors, and images.

Erlbaum.

Lewis,

H.

(1982).

The intellectual base

of

social work practice.

New

York: Haworth Press.

Mancoske,

R.

(1996). HIV/AIDS and suicide: Further precautions.

So-

cial Work,

3,

325-326.

Mattaini,

M.,

&

Kirk,

S.

A. (1993), Points and viewpoints: Misdiag-

nosing assessment.

Social Work,

38,231-233.

Popper,

K.

(1982). The open universe: An argument

for

indeterminism.

(From the postscript to

The Logic

of

Scientific Discovery,

origi-

nally published as

Logik der Forschung

in 1935 and revised,

1959). Totowa,

NJ:

Rowman

&

Littlefield.

Reynolds,

P.

(1971).

A

primer

in

theory construction.

New York:

Macmillan.

Richmond,

M.

(1917).

Social diagnosis.

New York: Russell Sage Foun-

dation.

Sperry, L. (1995).

Psychopharmacology and psychotherapy: Strategies

for maximum treatment outcomes.

New York: Bruner Mazel.

Winnicott, D.

W.

(1989).

Psychoanalytic explorations.

Cambridge,

MA:

Harvard University Press.

References

Cynthia

D.

Bisman

is

associate

professor,

Bryn

Mawr College, Graduate

School of Social

Work

Bryn

Mawr,

PA.

Abbott,

A.

(1988).

The system of professions: An essay

on

the division

of

expert labor.

Chicago: University

of

Chicago Press.

Bisman, C. D. (1994).

Social work practice: Cases and principles.

Pa-

cific Grove, CA: BrookslCole.

Bisman,

C.,

&

Hardcastle, D. (1999).

Integratrng research into prac-

tice:

A

model

for effective social work.

Pacific Grove,

C,4:

Brooks/Cole.

Blumer,

H.

(1969).

Symbolic interactionism.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

Bowlby,

J.

(1977). The making and breaking of affectional bonds.

British journal of Psychiatry,

230,

201-10.

Dubin,

R.

(1978).

Theory building.

New York: Free Press.

Goldstein,

E.

G. (1 995). Working with persons with AIDS. In E. Gold-

man (Ed.),

Ego

psychology and social work practice

(pp. 274-

281). New York: Free Press.

Greene, R.

R.

(1991). General systems theory.

In

R.R. Greene

&

P.

H.

Ehross (Eds.),

Human behavior and social work practice,

(pp.

227-259). New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

Hollis,

F.

(1970). The psychosocial approach tn the practice of case-

work.

In

R. Roberts

&

R. Nee (Eds.),

Theories of social casework,

(pp. 33-76). Chicago: University

of

Chicago Press.

Hopton,

J.

(1998). Risk assessment using psychological profiles tech-

niques: An evaluation of possibilities.

The British Journal nf

So-

cial Work,

28(2), 247-261.

Hudson,

W. W.

(1990). Computer based clinical practice.

In

L.

Videka-

Sherman

&

W.

J.

Reid (Eds.),

Advances

in

clinical social work

re-

search

(pp.

105.117).

Silver Spring,

MD:

NASW

Press.

Ikver, B.,

&

Sze, W. (1987). Social work and the psychiatric nosology

of schizophrenia.

Social Casework,

68,

131-139.

Author’s note: The author acknowledges thefollowing

Bryn

Mawr

MSS

studentsfor their case material: Jacqueline Stahl

and

Janine Wettrtone.

Original manuscript received:

July

1, 1998

Revision received December

28,

1998

Accepted: January 1, 1999

I

246