Evaluation of Express Entry: Early

Impacts on Economic Outcomes

and System Management

Research and Evaluation Branch

May 2020

For information about other Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) publications,

visit: www.cic.gc.ca/publications.

Available in alternative formats upon request.

Également disponible en français sous le titre : Évaluation du système Entrée express : impacts

préliminaires sur les résultats économiques et la gestion du système

Visit us online

Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada at www.cic.gc.ca

Facebook at www.facebook.com/CitCanada

YouTube at www.youtube.com/CitImmCanada

Twitter at @CitImmCanada

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Immigration,

Refugees and Citizenship, 2019

Ci4-210/2020E-PDF

978-0-660-35508-5

Project reference number: E3-2019

- 3 -

Table of contents

Executive summary 6

Evaluation of Express Entry: Impacts on Economic Outcomes and System Management.

Management Response Action Plan (MRAP) 9

1. Introduction 14

1.1. Purpose of evaluation 14

1.2. Brief Express Entry profile 14

1.2.1. The Comprehensive Ranking System 15

1.2.2. Economic programs covered under Express Entry 16

1.2.3. Characteristics of Express Entry immigrants admitted to Canada between 2015 and 2018 17

2. Methodology 21

2.1. Questions and scope 21

2.2. Data collection methods 21

2.3. Limitations and considerations 23

3. Early economic results 24

3.1. Labour market participation 24

3.2. Job history 25

3.2.1. First job after obtaining permanent residence 25

3.2.2. Job at time of survey 27

3.2.3. Professional advancement 28

3.3. Average employment income 29

3.3.1. Employment income 29

3.3.2. Effectiveness of the Comprehensive Ranking System 30

3.4. Labour market outcomes of Express Entry spouses 33

4. Responsiveness of Express Entry to labour market needs 34

4.1. Finding jobs quickly and pre-arranged offer of employment 34

4.2. Employers’ needs and experience with the Express Entry system 34

4.2.1. Employers’ needs 34

4.2.2. Employers’ experience with Express Entry system 35

5. Impact of Express Entry on profile of admissions under the economic programs 36

5.1. Profiles of economic immigrants admitted – 2015 to 2018 36

5.2. Impact on economic programs’ admission profiles 37

6. Other Express Entry outcomes 39

6.1. Contribution to official language minority communities 39

6.2. Impact of Express Entry on gender 40

6.2.1. Gender-based socio-demographic profile 40

6.2.2. Gender-based economic outcomes 41

6.3. Impact of Express Entry on efficiency, flexibility and integrity 43

6.3.1. Efficiency 43

6.3.2. Flexibility 46

6.3.3. Integrity 47

7 Conclusions and recommendations 49

Appendix A: The Comprehensive ranking system 51

Appendix B: Socio-demographic profiles 56

Appendix C: Evaluation matrix for the evaluation of IRCC’s Express Entry system 62

Appendix D: Regression results on employment income 66

Appendix E: Employer survey respondent profile 78

Appendix F: Regression results on employment income by gender 79

Appendix G: Case studies 84

- 4 -

List of tables

Table 1: Occupation types in which Express Entry and non-Express Entry respondents are employed at

time of first job after obtaining permanent residence 26

Table 2: Top 10 occupations in which Express Entry and non-Express Entry respondents were employed at

time of first job after obtaining permanent residence 27

Table 3: Socio-demographic profile of economic principal applicants* by immigration regime 36

Table 4: Occupation and quality of employment survey results for express entry and non-express entry

male and female respondents 42

Table 5: Historical processing time (in months) for 80% of cases 43

Table 6: Processing times of Express Entry applications (2015-2018) in months 44

Table 7: Permanent resident processing inventory (2009–2014) 44

Table 8: Permanent resident processing inventory (2015–2018) 44

Table 9: Refusal rates (2014–2018) 45

Table 10: Comprehensive ranking system— Core Human Capital factors (with spouse maximum 460;

without spouse maximum 500 – for all factors) 51

Table 11: Comprehensive ranking system—Spouse factors (maximum 40) 53

Table 12: Comprehensive ranking system skill—Transferability factors (maximum 100) 54

Table 13: Comprehensive ranking system—Additional points 55

Table 14: Non-express entry principal applicants and admissions 56

Table 15: Express Entry principal applicants and admissions 59

Table 16: Linear regression for the log of employment income in 2017 for Express Entry and non-Express

Entry principal applicants – 2015 and 2016 cohorts, model 1 66

Table 17: Linear regression for the log of employment income in 2017 for Express Entry and non-Express

Entry principal applicants – 2015 and 2016 cohorts, model 2 66

Table 18: Linear regression for the log of employment income in 2017 for Express Entry and non-Express

Entry principal applicants by immigration program – 2015 and 2016 cohorts 69

Table 19: Linear regression for the log of employment income in 2017 for Express Entry principal applicants

– 2015 and 2016 cohorts 71

Table 20: Analysis of the unique contribution of predictors to the R-Square 74

Table 21: Linear regression for the log of employment income at time of survey for Express Entry principal

applicants – 2015 to 2018 cohorts 75

Table 22: Linear regression for the log of employment income in 2017 for Express Entry and non-Express

Entry principal applicants by gender – 2015 and 2016 cohorts 79

Table 23: Linear regression for the log of employment income in 2017 for Express Entry principal applicants

by gender – 2015 and 2016 cohorts 81

Table 24: Labour market outlook and Express Entry principal applicant admissions – selected occupations 84

List of figures

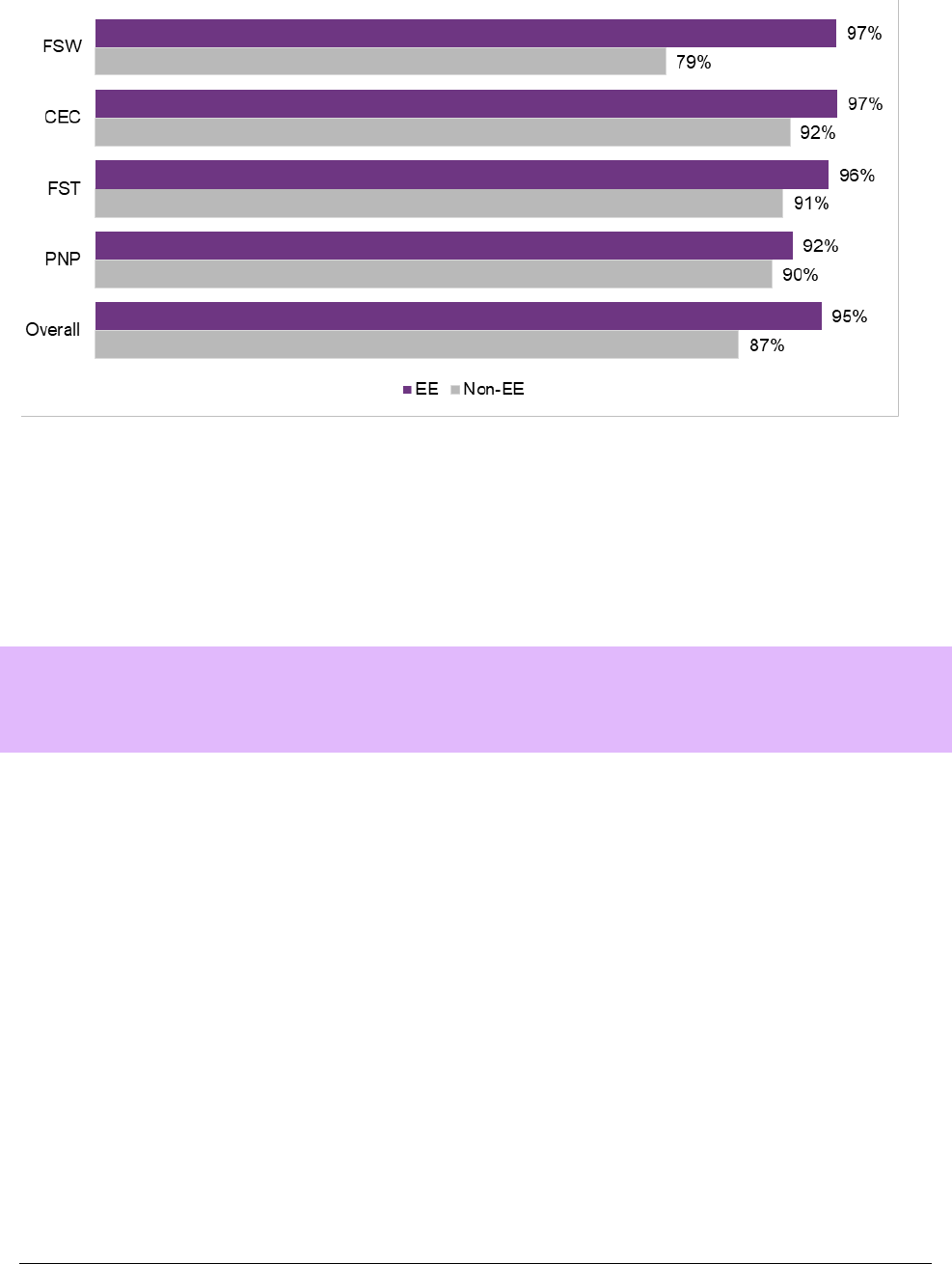

Figure 1: Incidence of employment income one year after admission by immigration categories, 2015 and

2016 admissions 25

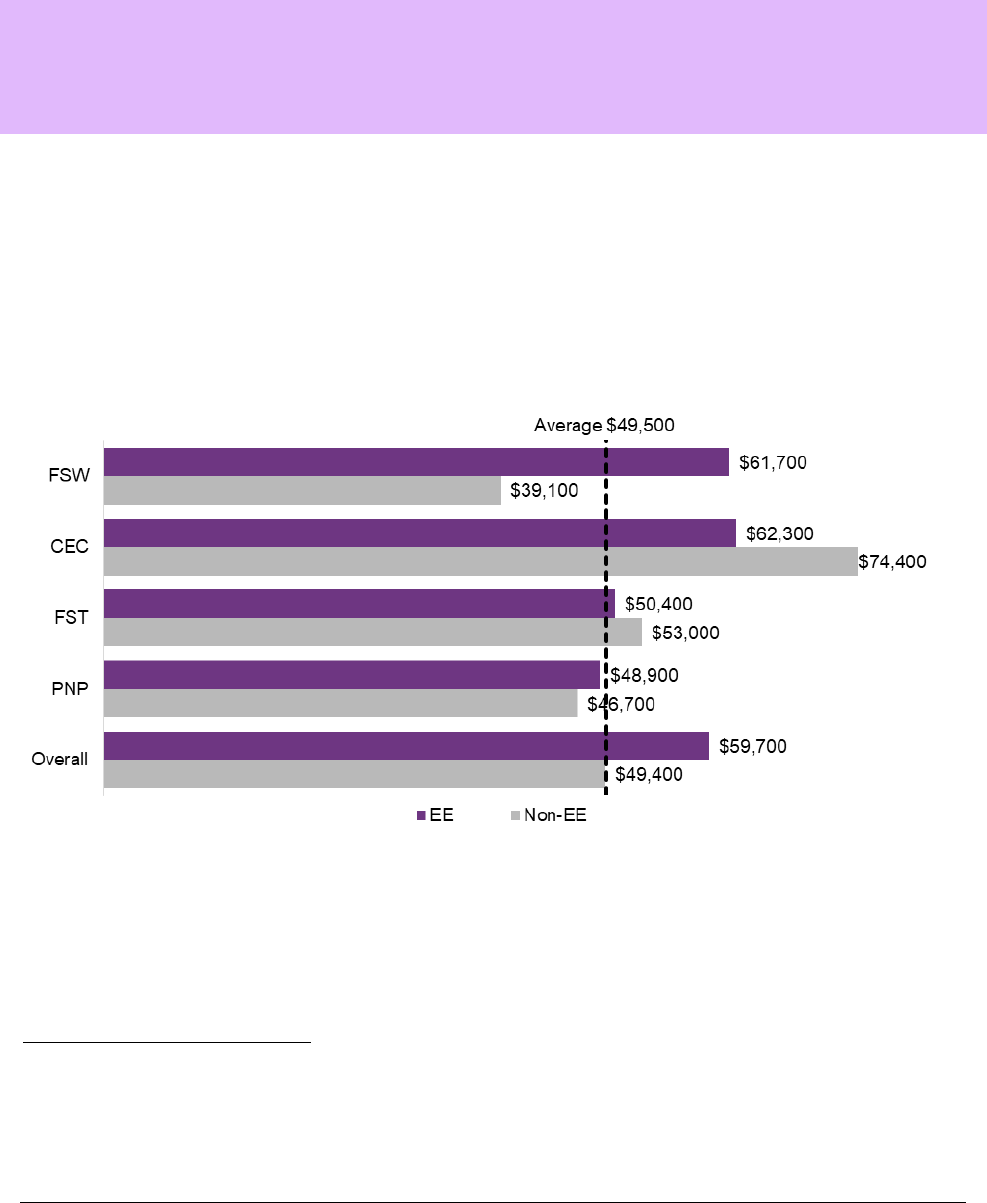

Figure 2: Average employment income one year after admission by immigration categories, 2015 and 2016

admissions 29

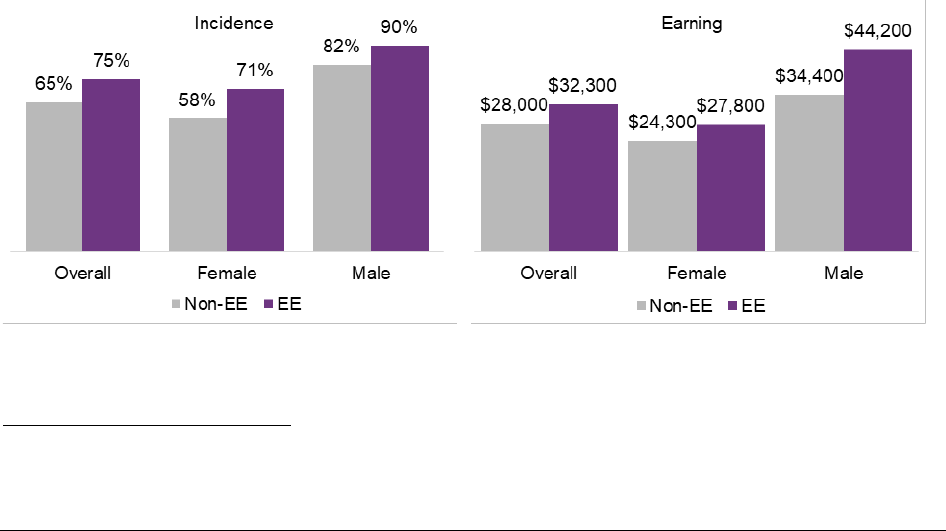

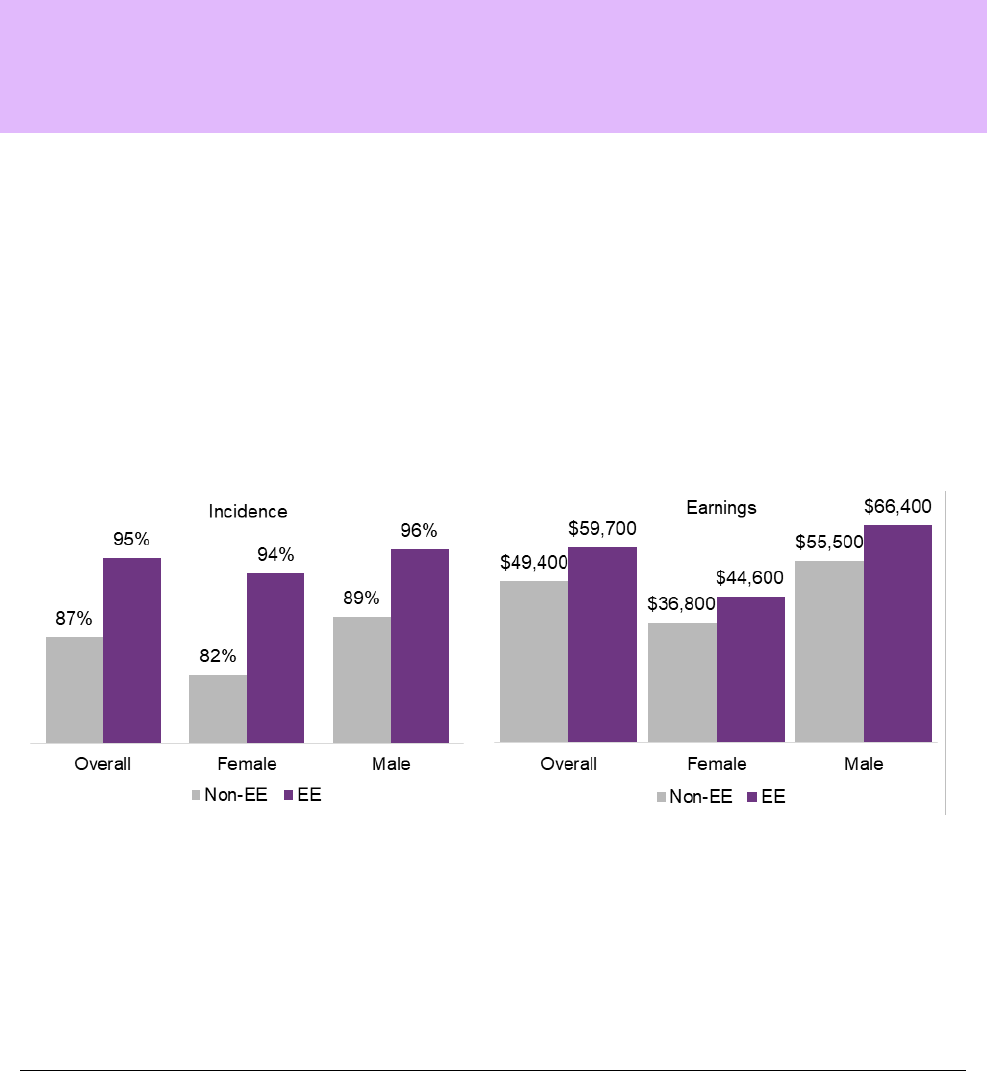

Figure 3: Incidence of employment income (a) and average employment income (b) for Express Entry and

non-Express Entry spouses 33

Figure 4: Incidence of employment income (a) and average employment income (b) for express entry and

non-express entry male and female principal applicants 41

- 5 -

List of acronyms

CEC Canadian Experience Class

CLB Canadian Language Benchmark

CMM Cost Management Model

CRS Comprehensive Ranking System

EE Express Entry

FPT Federal-Provincial-Territorial

FSTP Federal Skilled Trades Program

FSW Federal Skilled Worker

FSWP Federal Skilled Worker Program

GCMS Global Case Management System

IMDB Longitudinal Immigration Database

IRCC Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

IRPA Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

IRPR Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations

NOC National Occupation Codes

OLMC Official Language Minority Communities

PA Principal Applicant

PNP Provincial Nominee Program

PR Permanent Resident

TR Temporary Resident

- 6 -

Executive summary

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

Canada’s (IRCC) Express Entry system. The evaluation was conducted in fulfillment of

requirements under the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results, and considered issues of the

system’s effectiveness, with particular attention given to the early economic performance of

immigrants screened through Express Entry. The evaluation covered the period from 2015 to

2018.

Overview of the Express Entry system

Launched in January 2015, Express Entry is Canada’s evidence-based application management

system for certain economic immigration categories: Federal Skilled Worker Program, Federal

Skilled Trades Program, Canadian Experience Class and a portion of the Provincial Nominee

Program.

Express Entry was designed with three main objectives in mind: 1) flexibility in selection and

application management; 2) responsiveness to labour market and regional needs; and 3) speed in

application processing. Express Entry uses the Comprehensive Ranking System, which is an

evidence-based points system designed to identify candidates most likely to achieve high

employment earnings and who are able to maximize their economic performance in the Canadian

labour market. Therefore, the main focus of the evaluation was to assess the early economic

outcomes of economic principal applicants screened in using Express Entry.

Summary of conclusions and recommendations

Overall, findings from the evaluation show that early economic results for Express Entry

principal applicants are positive – they are demonstrating high levels of labour market

participation and solid results in terms of their employment income, as well as the type of

occupation in which they are employed.

Further, the evaluation found that Express Entry principal applicants generally outperform their

non-Express Entry counterparts. In particular, these early results show that 95% of Express Entry

principal applicants have become established economically and incidence of employment is high

across the four immigration categories. Of those who were working:

• 83% reported doing so in their primary occupation;

• Express Entry principal applicants earned 20% more than non-Express Entry principal

applicants; and

• 43% of Express Entry principal applicants were in occupations usually requiring university

education (NOC A) for their first job as permanent resident compared to 25% for non-Express

Entry principal applicants.

While early economic results were generally positive, it should be noted that the EE system was

designed to screen high human capital candidates who have the potential to achieve economic

success in the Canadian labour market over the longer term. Nevertheless, the early results are

encouraging and suggest that candidates screened through Express Entry are becoming

economically established with high employment rates and employment income.

Based on the evaluation findings and in support of the continued success of the Express Entry

system, the following four recommendations are proposed:

- 7 -

Monitoring of the system

The evaluation found Express Entry to be an effective screening mechanism to screen candidates

with higher potential for economic integration in Canada. While the CRS was designed to

identify those with potential for economic integration, including over the longer term, the

evaluation looked only at predictors of success in the first few years since implementation.

Specifically, while the evaluation found certain elements of the CRS had a significant impact on

short-term earnings (e.g., knowledge of the first official language), it also found that other

elements of the CRS had a limited impact on short-term economic outcomes of EE PAs.

Particularly, the skills transferability factors and spouse factors in the CRS were not found to

have clear impact on short-term economic outcomes. These findings point at the need to continue

monitoring the capacity of the CRS to identify EE PAs who will have positive economic

outcomes in the longer-term.

Recommendation 1: IRCC should continue to monitor the impact of the CRS on

earnings in the longer term, revalidating and streamlining it as needed, to focus on key

predictors of economic success.

Information gaps

The evaluation found that there were certain gaps in the information provided by candidates

when applying for permanent residence. In particular, while level of education is considered a

key human capital characteristic, it is not a mandatory field in the electronic application and, as a

result, not all candidates invited to apply for permanent residence submit information on their

educational credentials. The lack of this type of data limits the Department’s ability to fully

assess the impact of level of education on economic results. Collecting information on level of

education for all economic immigrants, including spouses and dependents, will allow IRCC to

monitor and more reliably measure the impact of education on the economic results of PAs

screened in through EE.

Recommendation 2: IRCC should collect information on the level of education of all

principal applicants, as well as information related to their spouses.

Management of integrity

At the launch of Express Entry, tools were introduced to improve capacity to detect potential

fraud and manage system risk. However, the Express Entry Validation and Verification Process

(VVP), which was intended to be a central integrity mechanism, was discontinued due to capacity

issues and lack of coordination. And with diffuse roles and responsibilities relating to the

integrity of the Express Entry system, the departmental approach has relied on officer experience

and minimal centralized oversight as opposed to addressing integrity with a systematic approach

as originally intended. Given the potential for fraud as changes to both the Express Entry system

and the CRS are made and as economic immigration grows, there is a need for a more purposeful

approach to monitoring integrity and emerging risk areas.

Recommendation 3: IRCC should develop and implement a systematic approach to

manage integrity in Express Entry.

- 8 -

Electronic system inefficiencies

Express Entry’s implementation as an electronic application system resulted in efficiencies in

application processing, though the electronic nature of the system introduced some challenges

associated with accessibility of client and application information. For example, clients are not

able to review their supporting documents once they have uploaded them and before submitting

to IRCC, rendering them unable to rectify any errors that may have been made, such as uploading

an incorrect document. In addition, it was noted that the system generates a new set of client

information each time a client updates their EE profile.

Such challenges have in turn led to complications related to litigation and ATIP management -

the complex nature of the electronic application system has made it difficult to produce evidence

when litigation occurs. Additionally, the electronic nature of the system makes it more difficult to

produce a Certified Tribunal Record for the court. With respect to ATIP, issues were identified

with the system’s technical design for extracting profile information. In addition, IRCC has

experienced an increased volumes of ATIP requests related to Express Entry applications, which

typically involves a large amount of documentation. These issues highlight an opportunity to

address certain inefficiencies in the electronic system for the benefit of clients and the

Department.

Recommendation 4: IRCC should develop and implement methods to:

− Allow Express Entry clients to view their application and uploaded documents prior

to, and after applying; and

− Improve accessibility of GCMS information to support the production of complete

records for operational, litigation and ATIP purposes.

- 9 -

Evaluation of Express Entry: Impacts on Economic Outcomes

and System Management. Management Response Action

Plan (MRAP)

The Express Entry system is an effective filtering mechanism, screening in individuals who have stronger

short-term economic performance in Canada compared to those not screened in through the system. And

while the evaluation found certain elements of the CRS had a significant impact on short-term earnings, it

also found that other elements of the CRS had a limited impact on short-term economic outcomes of EE

PAs. Particularly, the skills transferability factors and spouse factors were not found to have clear impact

on short-term economic outcomes. These findings suggest that IRCC should continue monitoring the

capacity of the CRS to identify EE PAs who will have positive economic outcomes in the longer-term.

Recommendation 1

IRCC should continue to monitor the impact of the CRS on earnings in the longer term,

revalidating and streamlining it as needed, to focus on key predictors of economic success.

Response

The CRS was designed to filter for candidates who are most likely to achieve high employment

earnings over the long term. This means that a full assessment of the CRS’s effectiveness would

only be feasible once earnings data for a cohort of immigrants sourced through Express Entry are

available for a ten-year period—i.e. in 2026, at the earliest.

IRCC recognizes the importance of ongoing monitoring of the CRS and of using that information

to recalibrate it as needed. The most robust data for this purpose would come from a continuing

linkage of IRCC Express Entry data with Statistics Canada’s Longitudinal Immigration Database,

contingent on funding and approval.

This linkage would allow IRCC to conduct analysis on a regular basis, as well as give academics

access to additional data to conduct their own research. The Department would benefit from that

research as well.

The original collaborative work between IRCC and Statistics Canada to develop the CRS focused

on the earnings of principal applicants that landed in 2004 or earlier. It is an appropriate time to

repeat this analysis with more recent data to see if the core human capital factors continue to

reliably predict long-term earnings as well as look at whether other outcomes and factors should

be incorporated. The results of the review would be presented to the DG Level Policy Committee.

This work will also help to inform future recommendations for potential adjustments to the CRS.

Actions

Action 1a: Develop a strategy to consistently link Express Entry data to Statistics Canada’s

Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB) on a regular basis to monitor the impact of the CRS

on earnings in the longer term.

− Accountability: Lead SPP. Support CDO, R&E, IB

− Completion date: Q4 2020–2021

- 10 -

Action 1b: Conduct a comprehensive review to revalidate the CRS based on more recent data,

and regularly every five years.

− Accountability: Lead SPPB. Support R&E, IB, CDO

− Completion date: Q1 2021–2022

Action 1c: Present results of review to Policy Committee, and regularly every five years.

− Accountability: Lead SPPB

− Completion date: Q3 2021–2022

The evaluation found that there were certain gaps in the information provided by candidates when

applying for permanent residence. In particular, while level of education is considered a key human capital

characteristic, it is not a mandatory field in the electronic application and, as a result, not all candidates

invited to apply for permanent residence applicants submit information on their educational credentials.

The lack of this type of data limits the Department’s ability to fully assess the impact of level of education

on economic results. Collecting information on level of education for all economic immigrants, including

spouses and dependents, will allow IRCC to monitor and more reliably measure the impact of education

on the economic results of PAs screened in through EE.

Recommendation 2

IRCC should collect information on the level of education of all principal applicants, as well as

information related to their spouses.

Response

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

IRCC already collects information on Express Entry principal applicants’, their spouses’ and

dependants’ educational history over the last ten years through the electronic application for

Permanent Residence. Analysis is required to determine whether a reliable measure of level of

education could be derived from this existing information for Express Entry principal applicants

and their spouses or partners. If the assessment determines that this data is not sufficiently robust,

a set of recommendations to collect this information from principal applicants and their spouses

or partners will be developed, taking into account implications for clients, privacy, IT systems,

and costs.

In addition, IRCC is also in the process of implementing a systems change that would allow it to

collect information on the field of study of Express Entry candidates. Such a list is essential for

conducting research on the impact of study experience on economic outcomes, as well as

monitoring required for continuing CRS improvements.

Actions

Action 2a: Assess and develop options to collect self-declared level of education data from

principal applicants and their spouses/partners; seek approval by the Director General Operations

Committee.

− Accountability: Lead SPPB. Support CDO, IB, TDSS

− Completion date: Q4 2020–2021

Action 2b: Develop a plan to implement the collection of self-declared education information,

contingent upon approval and available funding.

- 11 -

− Accountability: Lead SPPB. Support TDSS

− Completion date: Q1 2021–2022

At the launch of Express Entry, various tools were introduced to improve capacity to detect fraud and

manage risks. However, as the system evolved, the roles and responsibilities relating to the integrity of the

Express Entry system have become less clear and there was a lack of a systematic departmental

approach to address existing and emerging integrity issues. Given the potential for fraud as changes to

both the Express Entry system and the CRS are made and as economic immigration grows, there is a

need for a more purposeful and systematic approach to monitoring integrity and emerging risk areas.

Recommendation 3

IRCC should develop and implement a systematic approach to manage integrity in Express Entry.

Response

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

Maintaining the integrity of the Express Entry system is crucial. While significant efforts are

underway to uphold integrity within individual cases and within each processing network, it is

acknowledged that a more systematic departmental approach to managing integrity risk would be

beneficial.

The Department approach to managing integrity risk in the Express Entry program will include

the following:

− Increasing clarity around roles and responsibilities related to integrity risk management in

Express Entry

− A mechanism to systematically manage emerging risks

− A purposeful approach to monitoring integrity risks

Once the roles and responsibilities related to Express Entry’s integrity risk management are

agreed upon, a new Permanent Risk Management Table would be established at the Director

level to carry out a number of activities:

− Ensure that key stakeholders from across the department are engaged at all levels to ensure

an accurate and complete representation of the risks in the EE systems;

− Provide strategic and functional guidance on integrity risks in Express Entry, such as

providing tools and coordinating specific measures to manage the risks;

− Ensure critical risk areas impacting programs managed under Express Entry are understood

and addressed, including fraud, criminality, health, error, etc;

− Prioritize and assess key program risks, with items requiring decision referred to the

appropriate DG-level committee.

IRCC will also plan and report on targeted quality assurance exercises related to Express Entry,

including recommendations for mitigation as required.

- 12 -

Actions

Action 3a: Document and obtain consensus on the roles and responsibilities related to integrity

risk management in Express Entry.

− Accountability: Lead IRM. Support IPG, CN, IN, DN, CMB

− Completion date: Q4 2020–2021

Action 3b: Establish a Permanent Resident Risk Table which will provide a forum to share and

discuss risk information, drive coordinated efforts to identify and manage risks across the

integrated network, and support functional direction on effective integrity risk management in

Express Entry.

− Accountability: Lead IRM. Support IPG, CN, IN, DN, CMB

− Completion date: Q4 2020–2021

Action 3c: Create a baseline of existing and planned program integrity measures related to

Express Entry in order to identify possible gaps and areas for improvement.

− Accountability: Lead IRM. Support IPG, CN, IN, DN, CMB

− Completion date: Q4 2020–2021

Implementation of Express Entry as an electronic application system resulted in efficiencies in application

processing, though the electronic nature of the system introduced some challenges associated with

accessibility of client and application information. For example, clients are not able to review their

supporting documents once they have uploaded them and before submitting to IRCC, rendering them

unable to rectify any errors that may have been made, such as uploading an incorrect document. In

addition, the system generates a new set of client information each time a client updates their EE profile.

Such challenges have in turn led to complications related to litigation and ATIP management - the

complex nature of the electronic application system has made it difficult to produce evidence when

litigation occurs and also makes it more difficult to produce a Certified Tribunal Record for the court. With

respect to ATIP, issues were identified with the system’s technical design for extracting profile information.

In addition, IRCC has experienced increased volumes of ATIP requests related to Express Entry

applications, which typically involves a large amount of documentation. These issues highlight an

opportunity to address certain inefficiencies in the electronic system for the benefit of clients and the

Department.

Recommendation 4

IRCC should develop and implement methods to:

1. Allow Express Entry clients to view their application and uploaded documents prior to,

and after applying; and

2. Improve accessibility of GCMS information to support the production of complete

records for operational, litigation and ATIP purposes.

Response

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

The growing and changing digital demands on Canada’s immigration program are compounding

the pressures on the legacy IT systems which IRCC uses to deliver its services. IRCC has

developed a plan for stabilizing, modernizing and transforming its digital platforms to allow the

delivery of a world‑class client experience, while providing operational excellence, and meeting

program integrity objectives.

- 13 -

This plan includes a redesign of MyAccount as the cornerstone of IRCC’s digital client support.

The new MyAccount will enhance clients’ ability to self-serve by providing improved case status

information and additional functionality such as the ability for Express Entry clients to view

applications and uploaded documents prior to, and receive a copy after applying.

This work is part of a larger initiative underway to develop a new digital platform to help move

IRCC from paper-based to digital processing for all lines of business. It is expected that the new

platform will incorporate functionalities that allow for the efficient and effective production of

complete and readable records for operational, litigation and ATIP purposes for Express Entry.

This would allow records to be provided in a format that can be more easily stored, retrieved and

shared.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic and additional departmental priorities may require that IRCC

reconsider IT enabled priorities in order to meet immediate operational demands.

Actions

Action 4.1a: Submit business requirements to IT project intake for MyAccount 2.0 to TDSS

based on consultations with internal stakeholders. These business requirements will include

additional functionality to allow Express Entry clients to view their application and uploaded

documents prior to, and after applying.

− Accountability: Lead CEB. Support IPG, ATIP, CMB, TDSS

− Completion date: Q3 2020–2021

Action 4.1b: Determine prioritization, dependencies and implications to the Digital Platform

Modernization (DPM) initiative and a funding strategy to deliver MyAccount 2.0 requirements,

functions and features through IRCC’s IT governance process.

− Accountability: Lead TDSS/CEB. Support SPPB

− Completion date: Q4 2020–2021

Action 4.1c: Develop a plan to implement MyAccount 2.0.

− Accountability: Lead TDSS/CEB. Support SPPB

− Completion date: Q1 2021–2022

Action 4.2a: Conduct an analysis of Express Entry related issues in GCMS that affect the

efficient production of records, and from that analysis draft high-level business requirements to

be presented to the Director General level Operations Committee.

− Accountability: Lead IPG. Support CMB, ATIP, TDSS, CEB

− Completion date: Q4 2020–2021

Action 4.2b: Determine prioritization, dependencies and implications to the Digital Platform

Modernization (DPM) initiative and a funding strategy to deliver these requirements, functions

and features through IRCC’s IT governance process.

− Accountability: Lead TDSS/IPG. Support CMB, ATIP

− Completion date: Q4 2021–2022

Action 4.2c: Develop a plan to implement identified high-level business requirements.

− Accountability: Lead TDSS/IPG. Support CMB, ATIP

− Completion date: Q2 2021–2022

14

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of evaluation

This report presents the results of the evaluation of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

Canada’s (IRCC) Express Entry (EE) System and was conducted from January 2019 to

November 2019 in fulfillment of requirements under the 2016 Treasury Board Policy and

Directive on Results, considering primarily issues of system effectiveness. The primary area of

focus for the evaluation was the early economic performance of immigrants screened through EE,

and the evaluation also assessed the impact of the EE system on the economic immigration

categories. The evaluation also considered the impact of the EE system on two important

Government of Canada priorities, the official languages minority communities and gender, and

assessed flexibility, efficiency and integrity of EE.

1.2. Brief Express Entry profile

In the 2000s, there was a significant backlog of applications under the economic programs for

permanent residence. To respond to this issue, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

(IRPA) was amended through Bill C-50, the 2008 Budget Implementation Act. Bill C-50 made a

number of fundamental changes to the way in which immigration applications are managed: it

eliminated the obligation to process all applications received; and authorized the Minister to issue

Ministerial Instructions (MI) regarding which applications were prioritized for processing. These

MIs afforded the Minister the power to quickly limit the numbers of applications processed,

accelerate some applications, and return applications without processing them to a final

decision.

1

The Government of Canada long recognized the need for economic migration based on a slow

growing labour force, aging population and increasing demand for highly skilled labour. Coupled

with the high level of international competition for skilled migrants, there has been a known need

for Canada to improve its application system. As such, the Government of Canada decided to

change the way it manages the intake of economic permanent resident applications by launching

its EE system in January 2015.

EE is Canada’s evidence-based application management system for certain economic

immigration categories: Federal Skilled Worker Program (FSW), Federal Skilled Trades Program

(FST), Canadian Experience Class (CEC) and a portion of the Provincial Nominee Program

(PNP).

EE was designed with three main objectives in mind: 1) flexibility in selection and application

management, 2) responsiveness to labour market and regional needs and 3) speed in application

processing. In addition, the Comprehensive Ranking System is an evidence-based points system

designed to identify candidates most likely to achieve high employment earnings and therefore,

maximizing their economic performance in the Canadian labour market.

As a first step, prospective candidates complete an EE profile where they provide self-declared

information related to their education, work experience and other attributes. Those who meet the

minimum entry criteria for at least one of the three federally-managed economic immigration

1

Some sets of MIs restricted or capped applications from certain NOC. For example, under MI 8, an overall cap and sub-caps by

NOC for 24 eligible occupations, as well as a cap for Ph.D. applicants were introduced for the FSWP. Additionally, under MI 10,

six NOC B occupations could no longer be used to qualify for the CEC, and other NOC B occupations were sub-capped at 200

applications each. An overall cap was also applied to allow for 12,000 NOC 0 or A applications.

15

programs (FSW, FST, and CEC) are entered into a pool and, based on their profile, they are

awarded points using the publicly available Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS). These

candidates form a pool of prospective skilled immigrants to Canada, which IRCC,

Provinces/Territories and employers are able to consider.

2

ITAs are conducted in rounds that can be specific to one or more economic immigration

categories. For each round, IRCC determines the number of ITAs that will be sent to candidates.

During rounds, the number of ITAs are determined for the economic programs being targeted.

Based on the profiles in the pool and the number of ITAs issued, a minimum CRS cut-off is then

established for that round. Candidates with scores above the minimum CRS cut-off are

considered top-ranked candidates and will receive an invitation to apply. Applicants who receive

an ITA can then apply online for permanent residency through IRCC and will have their CRS

score, program eligibility and admissibility criteria assessed. If the applicant meets the eligibility

criteria and they and their dependents, meet the admissibility criteria, and still meets the

minimum CRS for that round, they are then approved for permanent residency.

1.2.1. The Comprehensive Ranking System

The Comprehensive Ranking System

3

(CRS) is the points-based system IRCC uses to determine

a candidate’s position in the EE pool. It ranks prospective skilled immigrants by looking at

specific factors such as work experience, language ability, education and other aspects which

have previously been shown to be associated with long-term economic success in Canada. As

such, the CRS was designed with the expectation that it would contribute to better economic

outcomes for economic immigrants.

4

The design of the CRS considered the short, medium and

long term impact of various components, while placing more weight on longer-term outcomes.

Factors in the CRS are generally grouped under two categories: Core points; and

Additional/bonus points.

Core points are made up of three components:

• Human capital factors refer to characteristics of the specific candidates themselves (e.g., age,

level of education, language proficiency).

• Spouse/common-law partner factors refer to characteristics of the candidate’s partner (e.g.,

spouse’s level of education, spouse’s Canadian work experience). The Comprehensive

Ranking System is comprised of two scales: one for single candidates, including married

candidates with a non-accompanying partner and one for candidates with an accompanying

partner. For candidates with an accompanying partner, human capital points are redistributed

to allow to consider their accompanying partner’s education, language proficiency and

Canadian work experience.

• Skill transferability points are assigned based on the understanding that the interaction

between certain factors increases a candidate’s potential for positive economic outcomes. For

example, given the positive effects of education on earnings are more readily transferred when

candidates have strong official language proficiency, candidates are awarded skill

2

Provinces and Territories can either ask economic immigrants to apply through the EE system, or can nominate economic

immigrants from the pool through an electronic portal. ESDC also provides a job matching service for EE candidates and

Canadian employers through Job Bank. Registering for Job Bank is voluntary for EE candidates.

3

For more information on the CRS, please see www.cic.gc.ca/english/immigrate/skilled/crs-tool.asp

4

Extensive econometric analysis were conducted to determine which factors, and to what extent, are best predictors of higher

employment earnings. Each factor was weighted to best reflect evidence on outcomes. The Comprehensive Ranking System

(CRS) was designed based on the results of this analysis.

16

transferability points if they are strong in both education and official language proficiency.

Additional points are awarded to candidates on the basis of policy or other objectives, and are not

necessarily related to human capital. At the time of conducting the evaluation, bonus points are

awarded based on provincial/territorial nomination, arranged offers of employment, post-

secondary education received in Canada, having a sibling who is a citizen or permanent resident

in Canada, and having high French language skills in addition to some English language skills.

5

Presently, candidates are able to earn a maximum of 1200 CRS points. Up to 600 Core points

may be awarded where 500 points are allocated between human capital factors and

spouse/common-law partner factors, where applicable, and 100 points are allocated for skill

transferability factors. A maximum of 600 additional points may also be awarded. A complete list

of the factors for which candidates receive points, and the respective values of each attribute are

available in Appendix A.

1.2.2. Economic programs covered under Express Entry

Four economic immigration programs are covered under EE: the Federal Skilled Worker

Program, the Canadian Experience Class, the Federal Skilled Trades Program, and the Provincial

Nominee Program.

The Federal Skilled Worker Program (FSWP) was developed as a part of Canada’s

immigration strategy, wherein permanent residents are selected on the basis of their ability to

become economically established in Canada. Applicants under the FSWP must have an

educational credential, meet minimum requirements of having at least one year of continuous

full-time paid employment, or the equivalent in continuous part-time employment within the last

10 years, in skill level 0, A or B in the National Occupation Classification (NOC), as well as

minimum language requirements of a Canadian Language Benchmark 7 or Niveaux de

compétence linguistique canadien 7. Applicants who meet the minimum requirements are then

given points for their work experience, education, language, age, arranged employment, and other

adaptability elements. Applicants who then meet a set pass mark (set at 67 points during the

period of the evaluation) will be eligible to receive an ITA.

The Canadian Experience Class (CEC) is a program that allows for skilled workers who have

Canadian work experience to become permanent residents. The CEC was introduced as a

pathway to increase Canada’s labour market responsiveness and global competitiveness in

attracting and retaining highly skilled workers and international graduates who had previously

demonstrated their ability to integrate into the Canadian labour market. CEC applicants are

required to have 12 months of Canadian work experience in NOC 0, A or B within the 36 months

prior to applying, and must also meet the language requirements associated with their respective

occupational level.

The Federal Skilled Trades Program (FSTP) allows skilled workers to become permanent

residents on the basis of their qualifications in a skilled trade. To be eligible for FSTP, a

candidate must meet minimum required language levels, have at least two years of full-time work

experience in a skilled trade within the five years prior to applying, meet the job requirements of

that skilled trade, and have either a valid job offer of full-time employment for a total period of at

5

Since the inception of the CRS, there have been several adjustments to these additional points. In November 2016 the points for

an arranged offer of employment were reduced from 600 points for all occupations, to 200 for NOC 00 occupations and 50 for all

other occupations. Points for Canadian study were also introduced. In addition, in June 2017, new points were added for siblings

in Canada and French-language proficiency. For more information see section 6.3.2.

17

least one year, or have a certificate of qualification in a skilled trade issued by a Canadian

provincial, territorial or federal authority.

The Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) is a jointly administered federal-provincial/territorial

immigration program that provides provinces and territories (PTs) with an opportunity to address

their specific labour market and economic development needs while distributing the benefits of

economic immigration across Canada. Under the authority of bilateral immigration agreements

with IRCC, eleven participating PTs establish their own streams, in consultation with IRCC, with

criteria that assess the candidate’s ability to become economically established in Canada and their

intention to reside in the nominating PT. If a candidate meets the PT PNP criteria, the PT issues a

nomination that allows the candidate to apply to IRCC for permanent residence. In addition,

under EE, PTs can create PNP streams with specific criteria that high skilled immigrants must

meet in addition to the eligibility criteria of one of the three federal economic immigration

programs.

PTs are able to nominate candidates through the EE pool (i.e., enhanced nominations), or through

PNP streams tailored to attract immigrants at all skills levels through paper-based applications

pre-dating EE (i.e., base nominations). PNP nomination allocations are determined by IRCC on

an annual basis. PTs have direct access to the EE pool through a portal that allows them to search

for, view and nominate candidates. In 2016, the enhanced allocation represented roughly 7,000

nominations over the approximate 25,500 base. Candidates who have a PT nomination in EE

receive an additional 600 points to their CRS score, which is usually sufficient to trigger an ITA

at the next round of invitations (subject to IRCC’s Ministerial Instructions for each particular

round of invitations).

At the onset of the EE, a processing hierarchy of economic programs was applied for those

candidates who were eligible to apply under multiple economic programs (e.g., meet the

minimum entry criteria for both FSW and CEC), with the exception of the PNP. The initial

hierarchy, in order of priority was FSTP, FSW, and CEC. During the timeframe covered by this

evaluation, changes were made with respect to the program hierarchy. Specifically, on June 26,

2015, the hierarchy was changed to prioritize the FSW, followed by the CEC, and finally the

FST. This change was made as prospective applicants did not want to apply under the more

complex FST if they had a choice. Further changes were applied to the hierarchy on March 9,

2016, with the priority becoming the CEC, followed by FSW and FST, in response to candidates’

strong preference to be invited to apply to the CEC, as well as to facilitate application processing.

1.2.3. Characteristics of Express Entry immigrants admitted to Canada between

2015 and 2018

A total of 200,868 EE immigrants – principal applicants (PA), spouses and dependants – were

admitted to Canada between 2015 and 2018. Of all EE admissions, over half (57%) were PAs.

The following characteristics were observed in EE PAs admitted between 2015 and 2018:

6

Immigration categories

Most of EE PAs were admitted either under the CEC (42%) or the FSWP (38%), while the

remainder were admitted under the PNP (17%) and the FSTP (2%).

When applying, EE PAs are assessed against the minimum entry criteria for each of the

programs. While 53% of the EE PAs were eligible for only one of the programs, 47% qualified

6

More details on the profile of economic immigrants can be found in Appendix B.

18

for more than one. As such, 73% of EE PAs admitted met the minimum entry criteria for the

FSWP, 56% met the criteria for the CEC, 18% for the FSTP, and 6% for the PNP.

Human capital attributes

Age

• 46% of EE PAs were between 20 and 29 years of age at admission; 51% of EE PAs were

between 30 to 44 years of age; and 3% were 45 years of age or more. Over time EE PAs

admitted tended to be younger with the share of EE PAs aged 35 years of age or more

decreasing (from 31% in 2015 to 20% in 2018) in favor of those aged 20 to 29 years old (34%

in 2015 to 46% in 2018).

Education

• 84% of EE PAs had a university degree. Overtime, the share of EE PAs with a university

education increased considerably: in 2015, only 38% reported having a university degree,

while 92% of EE PAs admitted in 2018 did so.

• Following the introduction of points in the CRS for Canadian study in November 2016, about

30% of the PAs admitted in 2017 and 2018 obtained points for having obtained a Canadian

post-secondary credential.

Knowledge of official languages

• The majority of EE PAs reported knowing English only (96%), while 0.5% reported knowing

French only, and 4% reported some knowledge of both official languages. The share of EE

PAs reporting some knowledge of both official languages increased slightly over time from

2% in 2015 to 4% in 2018.

• Based on CRS information, PAs usually had a high level of proficiency in their first official

language, with over 50% of them having obtained a level 10 on the Canadian Language

Benchmark (the highest level at which the CRS grants points for language proficiency), in

three of the four language skills assessed (listening, reading and speaking).

Temporary status

• Two thirds of EE PAs had previous temporary resident status in Canada (66%). 64% of EE

PAs had received a work permit and 39% had received a study permit. While the vast majority

(96%) of EE PAs admitted in 2015 had previous TR status in Canada, this share decreased

after the first year and represents about half (52%) of EE PA admissions in 2018.

• While 43% of all EE PAs had no or less than a year of work experience in Canada, 36% had

one year of experience, 16% had two years, and 6% had three years or more.

− In addition, 20% had received points in their application for having a job offer in Canada.

CRS Points

• EE PAs scored 413 points on average out of a maximum of 600 on the core CRS element

(human capital, spouse and skill transferability), and 606 on average out of a total of 1,200

possible points when including additional points for arranged employment, provincial

nomination, education in Canada, French-speakers and siblings in Canada.

• While the average core CRS points of PAs increased over time, reflecting the increasing

human capital of candidates, the total CRS score decreased because of the large influx of

19

applications with job offer points at the introduction of EE, and of the reduction in those job

offer points in November 2016.

Other Socio-demographics

Gender

• Close to two thirds of EE PAs were male (63%). While men represented 69% of the EE PA

admission in 2015, their share declined over time to represent 60% in 2018.

Country of Citizenship

• The most common countries of citizenship among PAs admitted were India (40%), China

(9%), Nigeria (5%), Philippines (4%) and the United Kingdom (4%). Together, these countries

represented 62% of all EE PAs admitted.

• The share of EE PAs originating from India more than doubled over time from 21% in 2015 to

45% in 2018.

Spouse

• About 42% of the PAs admitted had an accompanying spouse.

Occupations

NOC skill level of the intended occupation

• 47% of EE PAs intended to work in occupations usually requiring university education (NOC

A), 40% in occupations usually requiring college education or apprenticeship training (NOC B)

and 13% in management occupations (NOC 0). While individuals intending to work in

occupations usually requiring college education or apprenticeship training (NOC B) comprised

68% of admission in 2015, this share decreased over time in favor of individuals intending to

work in occupations usually requiring university education (from 25% in 2015 to 52% in 2018).

• Over one third of EE PAs (35%) intended to work in occupations related to natural and

applied sciences, 24% in business, finance and administration occupations, and 16% in sales

and service occupations. If individuals intending to work in sales and service occupations

accounted for a considerable portion of admissions in 2015 (44%), this share decreased over

time to represent only 12% of EE PAs in 2018.

Top Occupations

• The top five intended occupations for EE PAs were: professional occupations in natural and

applied sciences (25%), professional occupations in business and finance (9%), administrative

and financial supervisors and administrative occupations (8%), service supervisors and

specialized service occupations (8%), and technical occupations related to natural and applied

sciences (8%).

Location in Canada

Intended province of destination

• 91% of EE PAs indicated either Ontario (57%), Alberta (14%) or British Columbia (20%) as

the province of intended destination. Over half (52%) of PAs admitted in 2015 intended to

settle in Alberta, however, this proportion declined over the years (7% in 2018), while the

proportion intending to settle in Ontario increased (from 25% in 2015 to 65% in 2018).

As indicated above, the composition of EE PAs has changed over time in many respects,

including age, education, previous TR status in Canada, and intended occupation. These changes

were, to a large extent, the result of modifications to the CRS grid over time, mainly regarding

20

the significant reduction in points for arranged employment. While 72% of EE PAs admitted in

2015 had received points for a job offer, this share declined over time to represent 32% of EE PA

admission in 2016, 21% in 2017 and 10% in 2018.

21

2. Methodology

2.1. Questions and scope

The evaluation scope and approach were determined during the evaluation planning phase, in

consultation with IRCC branches involved in the design, management and delivery of EE. The

evaluation assessed the issues of performance of the EE system for the period of 2015 to 2018,

and was guided by the evaluation matrix, which outlines the evaluation questions and

performance indicators for EE (see Appendix C).The evaluation was conducted internally by

IRCC Evaluation Division.

7

The evaluation questions are as follows:

1. To what extent are economic immigrants screened under the EE system becoming

established economically?

2. Are the economic immigrants screened using the EE system performing better than those

admitted outside of the EE system?

3. To what extent has the EE system enabled the economic programs to be responsive to

labour market and regional needs?

4. How has the EE system impacted the profile of admissions under the economic programs

(FSW, CEC, FSTP, PNP)?

5. To what extent are the EE system and Economic Programs contributing to Official

Language Minority Communities (OLMC) initiative objectives?

6. What is the impact of the EE system on the gender distribution and outcomes within the

Economic program?

7. What have been the early impacts of EE on efficiency, flexibility and integrity on the

economic immigration programs?

2.2. Data collection methods

Data collection and analysis for this evaluation took place from January 2019 to September 2019

and included multiple lines of evidence that gathered qualitative and quantitative data from a

wide range of perspectives, including IRCC, PTs, other key stakeholders such as employers and

clients. The different lines of evidence supporting the evaluation are described below:

Data Analysis

Available performance data on EE and non-EE economic immigrants from IRCC’s Global Case

Management System (GCMS), including CRS information, as well as the Longitudinal

Immigration Database (IMDB)

8

were analyzed.

Although EE was introduced in 2015, about half of economic PAs admitted between 2015 and

2018 were not screened in using EE, as they had applied prior to January 2015 or were

considered under the base PNP applications. The evaluation used these non-EE PAs as a

comparison group against which to compare EE PAs. The EE group included individuals who

were admitted under the Federal Skilled Worker Program, the Canadian Experience Class, the

Federal Skilled Trades Program, as well as the Provincial Nominee Program. While the EE group

only included PAs intending to work in NOC 0, A or B occupations, there was no NOC

restriction applied to the non-EE group. As a result, a portion of the non-EE group includes PAs

7

Drafting of evaluation findings and recommendations preceded the current COVID-19 situation.

8

At time of analysis, the IMDB contained information up to tax year 2016. This was augmented with wages and salaries

information which provided data up to 2017.

22

intending to work in non NOC 0, A, or B occupations, unless specified otherwise.

9

Throughout

the report, “EE PAs” refers to PAs who were screened in under EE, while “non-EE PAs” refers to

PAs who were admitted to Canada under the same time frame (2015-2018) but were not screened

in through the EE system.

The IMDB was used to look at economic results. At the time of analysis, the IMDB contained

information up to tax year 2016. This was augmented with wages and salaries information which

provided data up to 2017. The evaluation was able link CRS data with data in the IMDB

(including wages and salaries information) for the first time.

In addition, IRCC relied on data from ESDC’s Job Bank for the first time for an evaluation,

which included information on employers’ province of operations, job offers and types of

occupations targeted. Information from these various sources was used to provide profiles and

performance information on the system.

Economic Immigrant Survey

An online survey was administered in February 2019 to economic PAs who received their

permanent residence between 2015 and 2018. A total of 44,409 PAs completed the survey, for an

overall response rate of 19%. This represents a margin of error of ± 0.42%, using a confidence

interval of 95%.

The majority of the analysis excluded PAs admitted in 2018, as most of this cohort would not

have been in Canada for a full year at the time of the survey. Unless specified otherwise the

analysis concentrated on PAs admitted between 2015 and 2017 (n=27,419)

Similar to the approach taken for the analysis of administrative data, the evaluation was also able

to benefit from having a direct comparison group against which to compare outcomes of EE PAs.

All survey results presented in this report are statistically significant.

Employer Survey

An exploratory online survey was administered to employers with active profiles on the Job Bank

website (www.jobbank.gc.ca) and were looking to fill job vacancies in NOC 0, A or B

occupations in 2018. Invitations to fill out the survey were sent out to 25,233 employers. A total

of 4,231 employers completed the survey, for an overall response rate of 17%.

Document Review

Relevant EE documents were reviewed to gather background and context on EE, as well as to

assess its performance. Documents reviewed include: government documents (e.g., budgets,

Reports on Plans and Priorities), documents related to policy changes and the management of the

system, and literature about the Canadian labour market.

Interviews

A total of 38 interviews were conducted across multiple branches within IRCC, as well as three

provincial representatives. Interviews included both those currently working directly or in

support of EE, as well as some involved at the launch of EE.

9

About 20% of the non-EE PAs were intending to work reported intending to work in occupations that were not in NOC 0, A or B

(i.e., in NOC C, D or other). These individuals were mainly admitted under the PNP base category of the non-EE PAs, and few

came under the FSWP.

23

Case Studies

10

The evaluation conducted four case studies on specific occupations of interest: pharmacists,

Information and Communications Technology (ICT) occupations, chefs and cooks, and food

services. The case studies involved a review of administrative data and documents, and an

analysis of the results from the Economic Immigrant survey for these specific occupations.

2.3. Limitations and considerations

There were a few limitations, although overall, they did not have a significant impact on the

evaluation findings:

• Given its recent implementation, this evaluation assessed the impact of the EE system in terms

of early client economic outcomes. However, the EE system was designed to maximize long-

term labour market outcomes. As such, while early results suggest a positive impact on

economic immigrant outcomes, longer-term analysis is still required to assess whether the

system is performing as intended.

• Since its introduction, changes were made to the CRS which may have changed the profile of

PAs in Canada and their economic outcomes. The evaluation only examined the economic

outcomes of EE candidates who applied in 2015 and 2016 with the IMDB due to a two year

lag in data availability. As a result, the economic analysis produced in this evaluation may not

reflect the current EE system. While it takes some time for candidates to be screened against

the revised CRS criteria and to be admitted as PRs, this was mitigated with the survey of

economic immigrants that included more recent admission cohorts.

• Level of education is not a mandatory field in the electronic application and, as a result, not all

candidates invited to apply for permanent residence submit information on their educational

credentials. As such, some candidates may choose not to go through an educational credential

assessment (ECA) process and have their education assessed for CRS points. As a result of

this, the level of education is unknown for some candidates, which limits the ability to fully

examine the impact of education on economic outcomes. Similarly, spousal human capital

fields are not mandatory, unless a candidate wishes to claim CRS points for their

accompanying spouse. Consequently, some spousal attributes will not be captured, which

limits the ability to fully examine the impact of spousal attributes on PA earnings as well as

the spouse’s own earnings.

• Although results from the survey of employers may serve as an indication of employers’

experiences with Job Bank, this survey was exploratory in nature. As such, survey results are

not meant to be representative of all Canadian employers who have used Job Bank.

Overall, the evaluation design employed numerous qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

The different lines of evidence were complementary and reduced information gaps, and the

results generally converged towards common findings. The triangulation of the multiple lines of

evidence, along with the mitigation strategies used in this evaluation are considered sufficient to

ensure that the findings are reliable and can be used with confidence.

10

As this was not considered a key line of evidence for this evaluation, results from the Case Studies are presented in Appendix G.

24

3. Early economic results

The following section presents early economic results of EE PAs on labour market participation,

employment income and type of employment.

While IMDB data presents information on all tax filers admitted within the first two years of the

inception of EE, for up to one year after admission, the survey of economic immigrants presents

results for PAs admitted between 2015 and 2017.

Throughout the section, outcomes of EE PAs are compared to their non-EE counterparts admitted

over the same time period to identify the impact of EE on early economic outcomes of

immigrants.

As will be discussed throughout Section 3, the vast majority of EE PAs have become established

economically. Moreover, economic results of EE candidates exceed those of non-EE candidates

admitted over the same time period, both in terms of incidence of employment and quality of

employment.

11

The evaluation also explored the early economic outcomes of spouses of PAs admitted under EE

and compared their outcomes to those that were not screened-in using EE.

3.1. Labour market participation

Finding: Nearly all Express Entry principal applicants had a job in their first years as a permanent

resident. Moreover, incidence of employment for Express Entry principal applicants exceeded that of non-

Express Entry principal applicants and the biggest difference between the two groups was found for

Federal Skilled Workers.

IMDB data indicates that the majority of EE and non-EE candidates were working the year they

were admitted to Canada as PRs (92% of EE PAs and 81% of non-EE PAs). This proportion

increased further in the first year following their admission (95% of EE PAs and 87% of non-EE

PAs).

The incidence of employment is higher for EE PAs compared to non-EE PAs. In the year of

admission, there was an 11 percentage point difference between EE and non-EE PAs. Although

smaller (i.e., 9 percentage points), the gap in incidence rate between EE and non-EE PAs

remained one year after admission.

11

For this comparison, the non-EE group includes PNP nominees who intended to work in NOC C and D occupations. PAs

screened in through EE are admitted on the basis that they intend to work in NOC O, A or B occupations.

25

Figure 1: Incidence of employment income one year after admission by immigration categories,

2015 and 2016 admissions

Source: IMDB 2016 – 2015-2016 admissions

When comparing by immigration categories and immigration regimes, for all immigration

categories, EE PAs always had a higher incidence of employment compared to non-EE PAs one

year after admission. Also CEC and FSW EE PAs had the highest incidence, followed closely by

the FST. The largest difference between EE and non-EE one year after admission was observed

for FSWs (97% vs. 79%, respectively).

3.2. Job history

Finding: Generally, Express Entry candidates are employed in higher skilled occupations than their non-

Express Entry counterparts and a greater proportion reported working in their primary occupation and in

jobs commensurate with their skills and experience.

3.2.1. First job after obtaining permanent residence

Closely aligned with incidence results from the IMDB, the results from the survey of economic

PAs show that nearly all EE (91%) and non-EE (89%) survey respondents reported that they

worked, either for pay or in self-employment, since they became a permanent resident in Canada.

Skill type

Table 1 presents the three most common industries (NOC skill type) in which EE and non-EE

respondents were working in their first job. About one third (34%) of EE respondents were

working in Natural and applied sciences and related occupations for their first job, and 22%

worked in Business, finance and administration occupation. While these two sectors were also the

most frequently reported by non-EE respondents for their first job in Canada as a PR (23% and

18% respectively), the proportion working in these sectors was lower than for EE respondents.

Sales and services occupations were the third type of occupations reported, with 18% of EE and

28% of non-EE respondents working in this type of occupation as their first job.

26

Table 1: Occupation types in which Express Entry and non-Express Entry respondents are

employed at time of first job after obtaining permanent residence

Skill type (first NOC digit) Description of skill type EE Non-EE

1 Business, finance and administration occupations 22% 18%

2 Natural and applied sciences and related occupations 34% 23%

3

Sales and services occupations

18% 28%

Source: Economic Immigrant Survey, 2019

Skill level

As to the skill level required for their first job as a PR, EE respondents were concentrated in

occupations requiring university education (NOC skill level A–43%). Another significant share

were working in occupations usually requiring college education or apprenticeship (NOC skill level

B–28%), and in management occupations (NOC skill level 0–11%). Together NOC skill level 0, A

and B accounted for 82% of occupations of EE respondents. They were however less to report

working in occupations usually requiring secondary school and/or occupation-specific training or

on-the-job training (NOC skill level C–11% and D–2%). Comparatively, non-EE respondents were

more distributed across all skill levels (skill level 0–11%, A–27%, B–28%, C–22% and D–8%), and

fewer were working in a first job requiring a NOC skill level of 0, A or B (66%).

Occupations

The ten most common occupations, as reported by EE and non-EE respondents, are presented in

Table 2. The most frequent occupations among EE respondents were Software engineers and

designers (8%) and Information systems analysts and consultants (5%). While these occupations

were also among the most frequent for the non-EE respondents, a smaller proportion reported

working in those occupations as their first job in Canada. Only one occupation for EE

respondents was below the NOC 0, A or B skill level (i.e., Retail salesperson at the NOC C skill

level, which accounted for 2% of the first job of EE respondents), while three of the top 10

occupations for non-EE were at the NOC C or D level (i.e., Retail salespersons and Transport

truck drivers at the NOC C skill level, and Food counter attendants, kitchen helpers and related

occupations at the NOC D skill level, together accounting for 8% of the first occupations of non-

EE respondents).

27

Table 2: Top 10 occupations in which Express Entry and non-Express Entry respondents were

employed at time of first job after obtaining permanent residence

NOC

(EE) Occupation (EE) %

NOC

(Non-EE) Occupation (Non-EE) %

0

Computer and information systems

managers

2% 0

Restaurant and food service

managers

2%

A

Software engineers and designers

8% 0

Banking, credit and other

investment managers

2%

A

Information systems analysts and

consultants

5% A

Software engineers and designers

4%

A

Post-secondary teaching and

research assistants

2% A

Information systems analysts and

consultants

3%

A

Financial auditors and accountants

2% A

Post-secondary teaching and

research assistants

2%

A University professors and lecturers 2% B Food service supervisors 2%

A

Computer programmers and

interactive media developers

2% B

Cooks

2%

B Cooks 2% C Retail salespersons 3%

B Food service supervisors 2% C Transport truck drivers 2%

C

Retail salespersons

2% D

Food counter attendants, kitchen

helpers and related occupations

3%

0 Other occupations 10% 0 Other occupations 7%

A&B Other occupations 47% A&B Other occupations 43%

C&D Other occupations 11% C&D Other occupations 22%

Source: Economic Immigrant Survey, 2019

3.2.2. Job at time of survey

Over one-third of survey respondents reported that they were no longer working in the same first

job and were working in a different job at the time of the survey (in February 2019). The majority

of EE (86%) and non-EE (82%) respondents reported working at the time of the survey. Of the

EE respondents who reported that they were working at the time of the survey, the majority

(83%) indicated that they were doing so in their primary occupation.

12

The top occupations, skill type and skill level for the job PAs held at the time of the survey were

similar to that of the first job for both EE and non-EE respondents. In addition, almost half of EE

(48%) and one-third of non-EE respondents (35%) were working in their intended occupation at

the time of the survey. Moreover, the majority of EE (81%) and non-EE (74%) respondents

reported that their current job meets or exceeds the expectations they had prior to becoming a PR.

Lastly, a greater proportion of EE respondents felt that their current job matched their education,

skills and experience compared to non-EE (77% vs. 67%). More specifically, 55% of EE

respondents and 45% of non-EE respondents felt that their current job matched their education,

skills and experience to a great extent.

12

The primary occupation refers to the job PAs have experience in (within the last 10 years) and on which they based their

immigration application.

28

3.2.3. Professional advancement

Finding: Express Entry and non-Express Entry principal applicants reported career advancement from an

occupational perspective and in terms of employment income. While non-Express Entry principal

applicants were more likely to report career advancement, their first jobs were more likely to be lower

skilled.

As mentioned above, over one-third of survey respondents reported that they were no longer

working in the same first job and indicated that they were working in a different job at the time of

the survey. When comparing EE and non-EE groups, a larger proportion of non-EE (41%) than

EE respondents (36%) reported that they changed jobs.

Professional advancement

For the most part, the change in jobs resulted in positive results for both EE and non-EE

respondents. In terms of occupational changes, survey results show that:

• a larger proportion of EE respondents (60%) reported that they had changed jobs within the

same NOC skill level compared to non-EE respondents (49%); and

• a larger proportion of non-EE (34%) than EE respondents (24%) indicated that they had

changed jobs to a higher NOC skill level.

While a larger proportion of non-EE respondents reported upward movement from an

occupational perspective, it should be noted that nearly one-third of non-EE respondents (30%)

who changed jobs were working in lower skilled (NOC C and D) occupations in their first job,

compared to 13% of EE respondents. As a result, non-EE respondents in lower skilled

occupations would have more opportunities for upward mobility.

Additionally, from an earnings perspective, the large majority of EE (83%) and non-EE (85%)

respondents reported an increase in their employment income when comparing self-reported

earnings for their first job to that of their job at the time of the survey.

Motivations for changing jobs and challenges

In terms of the motives for changing jobs, EE and non-EE respondents provided similar reasons

for moving to a new position. The most common reasons cited by respondents include:

• better pay and benefits (69% of both EE and non-EE);

• better advancement, promotion or development opportunities (63% of EE and 57% of non-EE);

• better working hours (36% of EE and 38% of non-EE); and

• to find a job in their area of specialization (36% of EE and 38% of non-EE).

While data from the IMDB and survey show positive employment results, EE and non-EE

respondents cited various challenges they encountered while finding work in Canada since

becoming a permanent resident. Survey results show that:

• a larger proportion of non-EE respondents (38%) cited “a lack of Canadian work experience”

as a challenge in finding work in Canada, compared to 31% for EE respondents;

• nearly one-quarter of non-EE respondents (22%) indicated that they encountered challenges in

having their credentials assessed and recognized, compared to 14% for EE respondents; and

29

• approximately one-quarter of EE and non-EE respondents also indicated that they encountered

challenges in accessing professional networks and that there were limited job opportunities in

their field.

3.3. Average employment income

Finding: Overall, Express Entry principal applicants have higher employment income on average than

their non-Express Entry counterparts. When compared to non-Express Entry, Express Entry principal

applicants in Federal Skilled Worker and Provincial Nominee Programs had higher earnings, while those

in Canadian Experience Class and Federal Skilled Trades had lower earnings.

3.3.1. Employment income

Analysis of IMDB data shows that, overall, EE PAs had higher incomes than their non-EE

counterparts, both in their year of admission and first full year since admission. One year after

admission, EE PAs earned on average $59,700, which is $10,300 more than the average income

of non-EE PAs or 20% higher. In addition, EE PAs had average earnings that were $10,200

above the Canadian-born (i.e., Canadian citizens by birth) average.

13

Figure 2: Average employment income one year after admission by immigration categories, 2015

and 2016 admissions

Source: (1) IMDB 2016 – 2015-2016 admissions and (2) Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue

no. 98-400-X2016205

While EE FSWs and PNs both reported average incomes higher than their non-EE counterparts

one year after admission, EE PAs admitted under the CEC and FST both reported lower

employment income than non-EE one year after admission, with the biggest differences were

observed within the FSW and CEC categories.

14

Although EE-CEC and EE-FST earned less than

their non-EE counterparts, when multivariate regressions were conducted (see section 3.3.2), no

13

While this may serve as an indication of how EE PAs are performing economically, this is an imperfect comparison group, as the

Canadian-born include individuals include individuals trained and working in all types of occupation, including lower skilled levels

such as NOC C and D occupations, whereas the EE group is more skilled and were screened based on their intention to work in

high skilled occupations. In addition, the non-EE group benefits from established social networks in Canada, of a better

knowledge of the Canadian context and a larger part of them are not new entrants on the Canadian labour market.

14

As discussed in section 1.2, MIs were issued pertaining to caps and exclusions for specific occupations prior to the introduction

of EE, which affects the occupational profile of the two groups.

30