Continuing Education Examination available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/cme/conted.html.

Early Release / Vol. 62 June 14, 2013

U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for

Contraceptive Use, 2013

Adapted from the World Health Organization Selected Practice

Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2nd Edition

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Early Release

CONTENTS (Continued)

Disclosure of Relationship

CDC, our planners, and our content experts wish to disclose

they have no financial interests or other relationships with

the manufacturers of commercial products, suppliers of com-

mercial services, or commercial supporters. Planners have

reviewed content to ensure there is no bias. This document will

not include any discussion of the unlabeled use of a product

or a product under investigational use, with the exception

that some of the recommendations in this document might

be inconsistent with package labeling. CDC does not accept

commercial support.

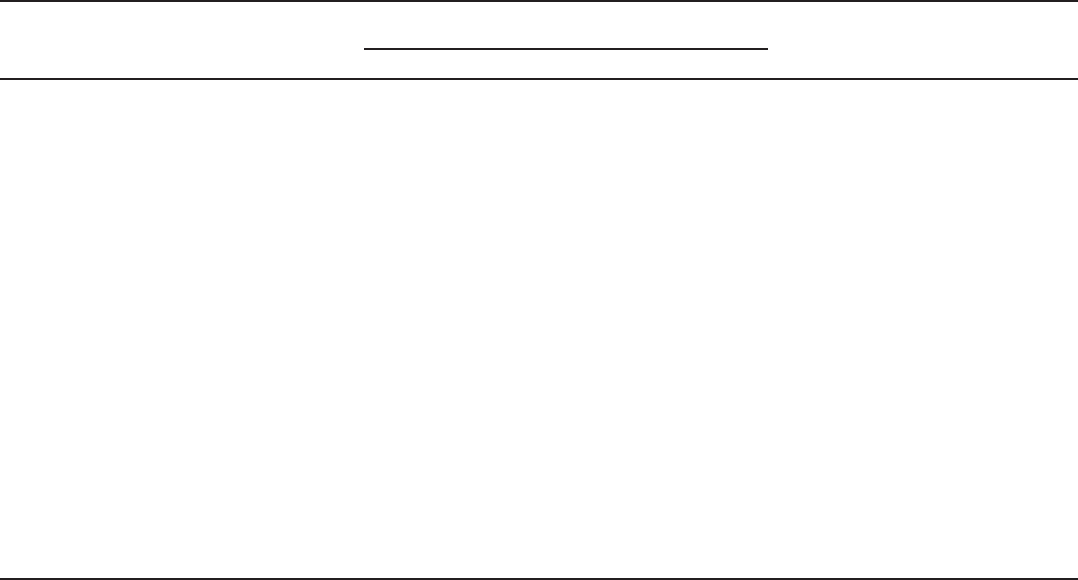

Front cover photos, left to right: intrauterine device, oral contraceptive pills, diaphragm, syringe for injectable contraceptives, male condom, transdermal

contraceptive patch, etonogestrel implant, vaginal ring.

The MMWR series of publications is published by the Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA 30333.

Suggested Citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Title]. MMWR 2013;62(No. RR-#):[inclusive page numbers].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH, Director

Harold W. Jaffe, MD, MA, Associate Director for Science

James W. Stephens, PhD, Director, Office of Science Quality

Denise M. Cardo, MD, Acting Deputy Director for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services

Stephanie Zaza, MD, MPH, Director, Epidemiology and Analysis Program Office

MMWR Editorial and Production Staff

Ronald L. Moolenaar, MD, MPH, Editor, MMWR Series

Christine G. Casey, MD, Deputy Editor, MMWR Series

Teresa F. Rutledge, Managing Editor, MMWR Series

David C. Johnson, Lead Technical Writer-Editor

Catherine B. Lansdowne, MS, Project Editor

Martha F. Boyd, Lead Visual Information Specialist

Maureen A. Leahy, Julia C. Martinroe,

Stephen R. Spriggs, Terraye M. Starr

Visual Information Specialists

Quang M. Doan, MBA, Phyllis H. King

Information Technology Specialists

MMWR Editorial Board

William L. Roper, MD, MPH, Chapel Hill, NC, Chairman

Matthew L. Boulton, MD, MPH, Ann Arbor, MI

Virginia A. Caine, MD, Indianapolis, IN

Barbara A. Ellis, PhD, MS, Atlanta, GA

Jonathan E. Fielding, MD, MPH, MBA, Los Angeles, CA

David W. Fleming, MD, Seattle, WA

William E. Halperin, MD, DrPH, MPH, Newark, NJ

King K. Holmes, MD, PhD, Seattle, WA

Timothy F. Jones, MD, Nashville, TN

Rima F. Khabbaz, MD, Atlanta, GA

Dennis G. Maki, MD, Madison, WI

Patricia Quinlisk, MD, MPH, Des Moines, IA

Patrick L. Remington, MD, MPH, Madison, WI

John V. Rullan, MD, MPH, San Juan, PR

William Schaffner, MD, Nashville, TN

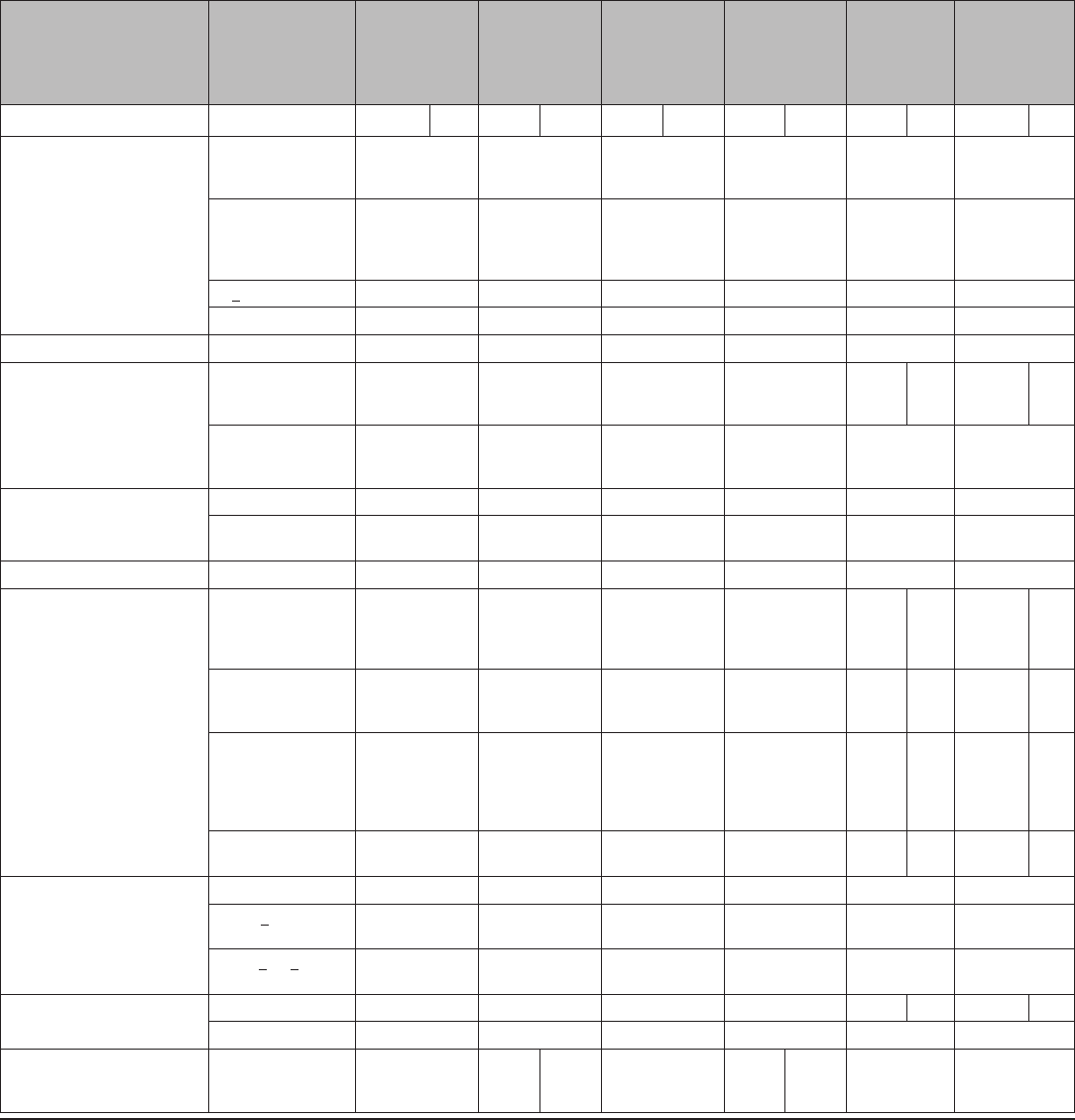

CONTENTS

Introduction ............................................................................................................1

Methods

....................................................................................................................2

How To Use This Document

............................................................................... 3

Summary of Changes from WHO SPR

............................................................ 4

Contraceptive Method Choice

.........................................................................4

Maintaining Updated Guidance

......................................................................4

How To Be Reasonably Certain that a Woman Is Not Pregnant

............ 5

Intrauterine Contraception

................................................................................7

Implants

................................................................................................................. 14

Injectables

............................................................................................................. 17

Combined Hormonal Contraceptives

......................................................... 22

Progestin-Only Pills

............................................................................................ 29

Standard Days Method

..................................................................................... 33

Emergency Contraception

.............................................................................. 34

Female Sterilization

........................................................................................... 35

Male Sterilization

................................................................................................ 36

When Women Can Stop Using Contraceptives

....................................... 37

Conclusion

............................................................................................................ 37

Acknowledgment

............................................................................................... 38

References

............................................................................................................. 38

Appendix A: Summary Chart of U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for

Contraceptive Use, 2010

.................................................................................. 47

Appendix B: When To Start Using Specific Contraceptive

Methods

.............................................................................................................. 55

Appendix C: Examinations and Tests Needed Before Initiation of

Contraceptive Methods

................................................................................. 56

Appendix D: Routine Follow-Up After Contraceptive Initiation

........ 57

Appendix E: Management of Women with Bleeding Irregularities

While Using Contraception

.......................................................................... 58

Appendix F: Management of the IUD when a Cu-IUD or an LNG-IUD

User Is Found To Have Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

........................... 59

Early Release

MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62 1

U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2013

Adapted from the World Health Organization Selected Practice

Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2nd Edition

Prepared by

Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Summary

The U. S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use 2013 (U.S. SPR), comprises recommendations that

address a select group of common, yet sometimes controversial or complex, issues regarding initiation and use of specific contraceptive

methods. These recommendations are a companion document to the previously published CDC recommendations U.S. Medical

Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010 (U.S. MEC). U.S. MEC describes who can use various methods of contraception,

whereas this report describes how contraceptive methods can be used. CDC based these U.S. SPR guidelines on the global family

planning guidance provided by the World Health Organization (WHO). Although many of the recommendations are the same

as those provided by WHO, they have been adapted to be more specific to U.S. practices or have been modified because of new

evidence. In addition, four new topics are addressed, including the effectiveness of female sterilization, extended use of combined

hormonal methods and bleeding problems, starting regular contraception after use of emergency contraception, and determining

when contraception is no longer needed. The recommendations in this report are intended to serve as a source of clinical guidance

for health-care providers; health-care providers should always consider the individual clinical circumstances of each person seeking

family planning services. This report is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice for individual patients.

Persons should seek advice from their health-care providers when considering family planning options.

Introduction

Unintended pregnancy rates remain high in the United

States; approximately 50% of all pregnancies are unintended,

with higher proportions among adolescent and young women,

women who are racial/ethnic minorities, and women with lower

levels of education and income (1). Unintended pregnancies

increase the risk for poor maternal and infant outcomes (2)

and in 2002, resulted in $5 billion in direct medical costs in the

United States (3). Approximately half of unintended pregnancies

are among women who were not using contraception at the

time they became pregnant; the other half are among women

who became pregnant despite reported use of contraception

(4). Therefore, strategies to prevent unintended pregnancy

include assisting women at risk for unintended pregnancy and

their partners with choosing appropriate contraceptive methods

and helping women use methods correctly and consistently

to prevent pregnancy. In 2010, CDC first adapted global

guidance from the World Health Organization (WHO) to

help health-care providers counsel women, men, and couples

about contraceptive method choice. The U.S. Medical Eligibility

Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010 (U.S. MEC), focuses on who

can safely use specific methods of contraception and provides

recommendations for the safety of contraceptive methods for

women with various medical conditions (e.g., hypertension and

diabetes) and characteristics (e.g., age, parity, and smoking status)

(Appendix A) (5). The recommendations in this new guide, U.S.

Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2013

(U.S. SPR), focuses on how contraceptive methods can be used

and provides recommendations on optimal use of contraceptive

methods for persons of all ages, including adolescents.

During the past 15 years, CDC has contributed to the

development and updating of the WHO global family planning

guidance. CDC has supported WHO by coordinating the

identification, critical appraisal, and synthesis of the scientific

evidence on which the WHO guidance is based. In 2002,

WHO published the first edition of the Selected Practice

Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (WHO SPR), which

presented evidence-based global guidance on how to use

contraceptive methods safely and effectively once they are

deemed to be medically appropriate. Since then, WHO has

regularly updated its guidance on the basis of new evidence,

and the document is now in its second edition (6), with an

additional update in 2008 (7). The WHO global guidance is

not intended for use directly by health-care providers; rather,

WHO intends for the guidance to be used by local or national

policy makers, family planning program managers, and the

The material in this report originated in the National Center for

Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Ursula Bauer,

PhD, Director; Division of Reproductive Health, Wanda Barfield,

MD, Director.

Corresponding preparer: Kathryn M. Curtis, PhD, Division of

Reproductive Health. Telephone: 770-488-5200; E-mail: [email protected].

Early Release

2 MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62

scientific community as a reference when they develop family

planning guidance at the country or program level (6). For

example, the United Kingdom adapted WHO SPR and in

2002 published the U.K. Selected Practice Recommendations

for Contraceptive Use for use by U.K. health-care providers (8).

CDC initiated a formal adaptation process to create U.S.

SPR, using both the second edition of WHO SPR (6) and the

2008 update (7) as the basis for the U.S. version. Although

much of the guidance is the same as the WHO guidance,

the recommendations are specific to U.S. family planning

practice. In addition, guidance on contraceptive methods not

available in the United States has been removed, and four

new topics for guidance have been added (the effectiveness

of female sterilization, extended use of combined hormonal

methods and bleeding problems, starting regular contraception

after use of emergency contraception, and determining when

contraception is no longer needed). This document contains

recommendations for health-care providers for the safe and

effective use of contraceptive methods and addresses provision of

contraceptive methods and management of side effects and other

problems with contraceptive method use. Although the term

woman is used throughout this report, these recommendations

refer to all females of reproductive age, including adolescents.

Adolescents are identified throughout this document as a special

population that might benefit from more frequent follow-up.

These recommendations are meant to serve as a source of

clinical guidance for health-care providers; health-care providers

should always consider the individual clinical circumstances

of each person seeking family planning services. This report is

not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice

for individual patients; persons should seek advice from their

health-care providers when considering family planning options.

Methods

CDC initiated a process to adapt WHO SPR for the

United States. This adaptation process included four steps:

1) determining the scope of and process for the adaptation,

including an October 2010 meeting in which individual

feedback was solicited from a small group of partners and

experts; 2) preparing the systematic reviews of the evidence

during October 2010–September 2011 to be used for the

adaptation, including peer review; 3) convening a larger

meeting of experts in October 2011 to examine the evidence

and receive input on the recommendations; and 4) finalizing

recommendations by CDC.

During October 21–22, 2010, CDC convened a meeting of 10

partners and U.S. family planning experts in Atlanta, Georgia, to

discuss the scope of and process for a U.S. adaptation of WHO

SPR. A list of participants is provided at the end of this report.

CDC identified the specific WHO recommendations that might

benefit from modification for the United States. Criteria used to

modify the WHO recommendations included the availability of

new scientific evidence or the context in which family planning

services are provided in the United States. CDC also identified

several WHO recommendations that needed additional specificity

to be useful for U.S. health-care providers, as well as the need for

additional recommendations not currently included in WHO

SPR. In addition, the meeting members discussed removing

recommendations that provide information about contraceptive

methods that are not available in the United States.

Representatives from CDC and WHO conducted systematic

reviews of the scientific evidence for each of the WHO

recommendations being considered for adaptation and for each

new topic being considered for addition to the guidance. The

purpose of these systematic reviews was to identify evidence

related to the common clinical challenges associated with the

recommendations. When no direct evidence was available,

indirect evidence and theoretical issues were considered. Standard

guidelines were followed for reporting systematic reviews (9,10),

and strength and quality of the evidence were graded using the

system of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (11). Each

complete systematic review was peer reviewed by two or three

experts before its use in the adaptation process. Peer reviewers,

who were identified from the list of persons scheduled to

participate in the October 2011 meeting, were asked to comment

on the search strategy, list of articles included in the reviews, and

the summary of findings. The systematic reviews were finalized

and provided to participants before the October 2011 meeting

and were published in May 2013 (12–30).

During October 4–7, 2011, CDC convened a meeting in

Atlanta, Georgia, of 36 experts who were invited to assist in

guideline development and provide their perspective on the

scientific evidence presented and the discussions on potential

recommendations that followed. The group included obstetrician/

gynecologists, pediatricians, family physicians, nurse-midwives,

nurse practitioners, epidemiologists, and others with research and

clinical practice expertise in contraceptive safety, effectiveness, and

management. All participants received all of the systematic reviews

before the meeting. During the meeting, the evidence from the

systematic review for each topic was presented, and participants

discussed the evidence and the translation of the scientific evidence

into recommendations that would meet the needs of U.S. health-

care providers. In particular, participants discussed whether and

how the U.S. context might be different from the global context

and whether these differences suggested any need for modifications

to the global guidance. CDC gathered the input from the experts

during the meeting and finalized the recommendations in this

Early Release

MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62 3

report. The document was peer reviewed by meeting participants,

who were asked to comment on specific issues that were raised

during the meeting. Feedback also was received from an external

review panel, composed of health-care providers who had not

participated in the adaptation meetings. These providers were

asked to provide comments on the accuracy, feasibility, and clarity

of the recommendations, as well as to provide other comments.

Areas of research that need additional investigation also were

considered during the meeting (31).

How To Use This Document

The recommendations in this report are intended to

help health-care providers address issues related to use of

contraceptives, such as how to help a woman initiate use of a

contraceptive method, which examinations and tests are needed

before initiating use of a contraceptive method, what regular

follow-up is needed, and how to address problems that often

arise during use, including missed pills and side effects such as

unscheduled bleeding. Each recommendation addresses what

a woman or health-care provider can do in specific situations.

For situations in which certain groups of women might be

medically ineligible to follow the recommendations, comments

and reference to U.S. MEC are provided (5). The full U.S.

MEC recommendations and the evidence supporting those

recommendations were published in 2010 (5).

The information in this document is organized by

contraceptive method, and the methods generally are presented

in order of effectiveness, from highest to lowest. However, the

recommendations are not intended to provide guidance on

every aspect of provision and management of contraceptive

method use. Instead, they use the best available evidence

to address specific issues regarding common, yet sometimes

complex, clinical issues. Each contraceptive method section

generally includes information about initiation of the method,

regular follow-up, and management of problems with use (e.g.,

usage errors and side effects). Each section first provides the

recommendation and then includes a comments and evidence

section, which includes comments about the recommendations

and a brief summary of the scientific evidence on which the

recommendation is based.

Recommendations in this document are provided for

permanent methods of contraception, such as vasectomy

and female sterilization, as well as for reversible methods of

contraception, including the copper-containing intrauterine

device (Cu-IUD); levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD);

the etonogestrel implant; progestin-only injectables; progestin-

only pills (POPs); combined hormonal contraceptive methods

that contain both estrogen and a progestin, including combined

oral contraceptives (COCs), a transdermal contraceptive patch,

and a vaginal contraceptive ring; and the standard days method

(SDM). Recommendations also are provided for emergency

use of the Cu-IUD and emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs).

For each contraceptive method, recommendations are provided

on the timing for initiation of the method and indications for

when and for how long additional contraception, or a back-up

method, is needed. Many of these recommendations include

guidance that a woman can start a contraceptive method at any

time during her menstrual cycle if it is reasonably certain that

the woman is not pregnant. Guidance for health-care providers

on how to be reasonably certain that a woman is not pregnant

is provided.

For each contraceptive method, recommendations include the

examinations and tests needed before initiation of the method.

These recommendations apply to persons who are presumed to

be healthy. Those with known medical problems or other special

conditions might need additional examinations or tests before

being determined to be appropriate candidates for a particular

method of contraception. U.S. MEC might be useful in such

circumstances (5). Most women need no or very few examinations

or tests before initiating a contraceptive method. The following

classification system was developed by WHO and adopted by

CDC to categorize the applicability of the various examinations

or tests before initiation of contraceptive methods (6):

Class A:These tests and examinations are essential and

mandatory in all circumstances for safe and effective use of

the contraceptive method.

Class B: These tests and examinations contribute substantially

to safe and effective use, although implementation can be

considered within the public health context, service context, or

both. The risk for not performing an examination or test should

be balanced against the benefits of making the contraceptive

method available.

Class C: These tests and examinations do not contribute

substantially to safe and effective use of the contraceptive method.

These classifications focus on the relation of the examinations

or tests to safe initiation of a contraceptive method. They

are not intended to address the appropriateness of these

examinations or tests in other circumstances. For example,

some of the examinations or tests that are not deemed necessary

for safe and effective contraceptive use might be appropriate

for good preventive health care or for diagnosing or assessing

suspected medical conditions. Systematic reviews were

conducted for several different types of examinations and tests

to assess whether a screening test was associated with safe use

of contraceptive methods.Because no single convention exists

for screening panels for certain diseases, including diabetes,

Early Release

4 MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62

lipid disorders, and liver diseases, the search strategies included

broad terms for the tests and diseases of interest.

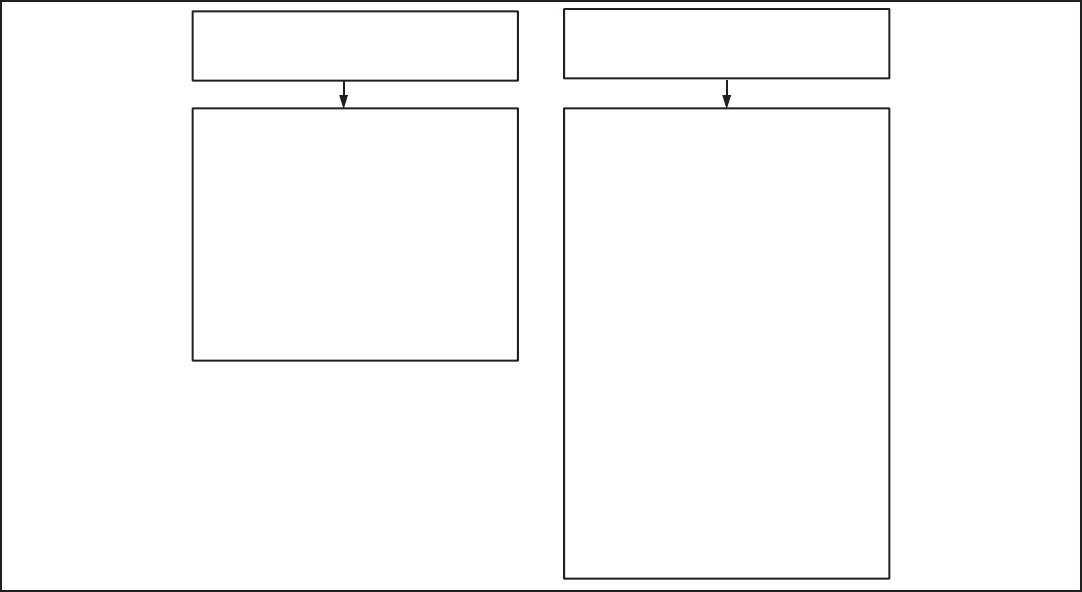

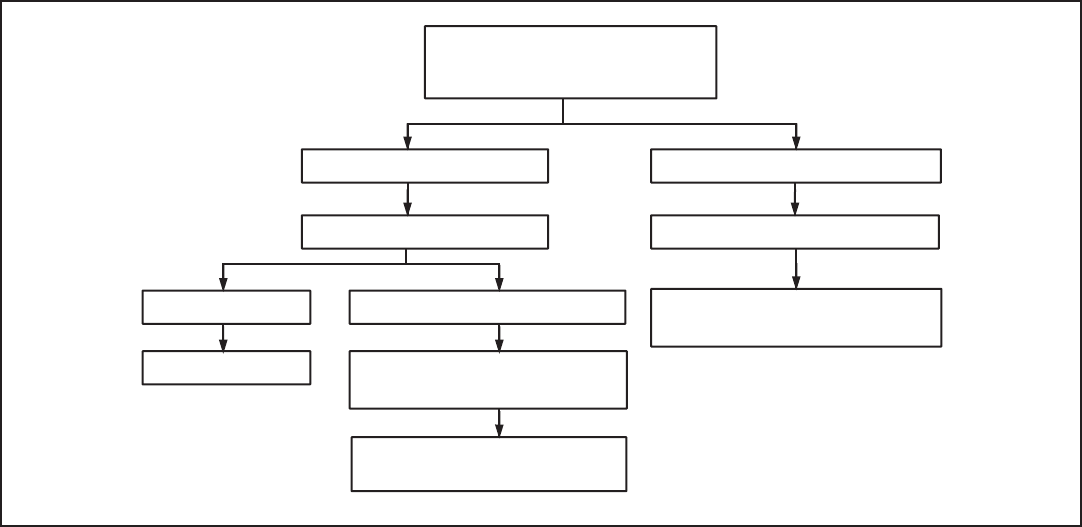

Summary charts and clinical algorithms that summarize

the guidance for the various contraceptive methods have been

developed for many of the recommendations, including when

to start using specific contraceptive methods (Appendix B),

examinations and tests needed before initiating the various

contraceptive methods (Appendix C), routine follow-up after

initiating contraception (Appendix D), management of bleeding

irregularities (Appendix E), and management of IUDs when

users are found to have pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

(Appendix F). These summaries might be helpful to health-care

providers when managing family planning patients. Additional

tools are available on the U.S. SPR website (http://www.cdc.

gov/reproductivehealth/UnintendedPregnancy/USSPR.htm).

Summary of Changes from WHO SPR

Much of the guidance in U.S. SPR is the same or very similar

to the WHO SPR guidance. U.S. SPR includes new guidance

on the use of the combined contraceptive patch and vaginal

ring, as well as recommendations for four new topics:

• howtostartregularcontraceptionaftertakingECPs

• management of bleeding irregularitiesamongwomen

using extended or continuous combined hormonal

contraceptives (including pills, the patch, and the ring)

• whenawomancanrelyonfemalesterilizationforcontraception

• whenawomancanstopusingcontraceptivesandnotbe

at risk for unintended pregnancy

Adaptations to the WHO SPR recommendations include

1) changes to the length of the grace period for depot

medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) reinjection, 2) differences

in some of the examinations and tests recommended before

contraceptive method initiation, 3) differences in some of the

recommendations for management of bleeding irregularities

because of new data and drug availability in the United States,

and 4) a modified missed pill algorithm to respond to concerns

of the CDC expert group and other reviewers that simplified

algorithms are preferable.

Contraceptive Method Choice

Many elements need to be considered individually by a

woman, man, or couple when choosing the most appropriate

contraceptive method. Some of these elements include

safety, effectiveness, availability (including accessibility and

affordability), and acceptability.

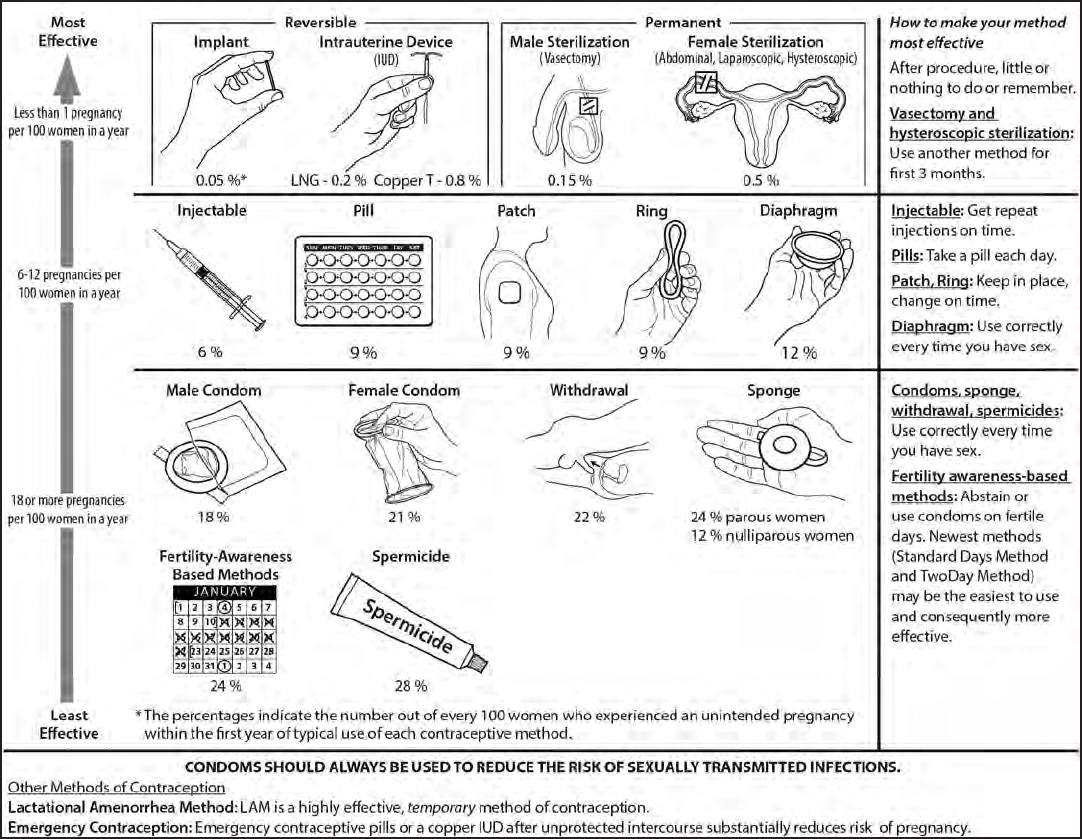

Contraceptive method effectiveness is critically important

in minimizing the risk for unintended pregnancy, particularly

among women for whom an unintended pregnancy would

pose additional health risks. The effectiveness of contraceptive

methods depends both on the inherent effectiveness of the

method itself and on how consistently and correctly it is used

(Table 1). Both consistent and correct use can vary greatly

with characteristics such as age, income, desire to prevent

or delay pregnancy, and culture. Methods that depend on

consistent and correct use by clients have a wide range of

effectiveness between typical and perfect users. IUDs and

implants are considered long-acting, reversible contraception

(LARC); these methods are highly effective because they do not

depend on regular compliance from the user. LARC methods

are appropriate for most women, including adolescents and

nulliparous women. All women should be counseled about

the full range and effectiveness of contraceptive options for

which they are medically eligible so that they can identify the

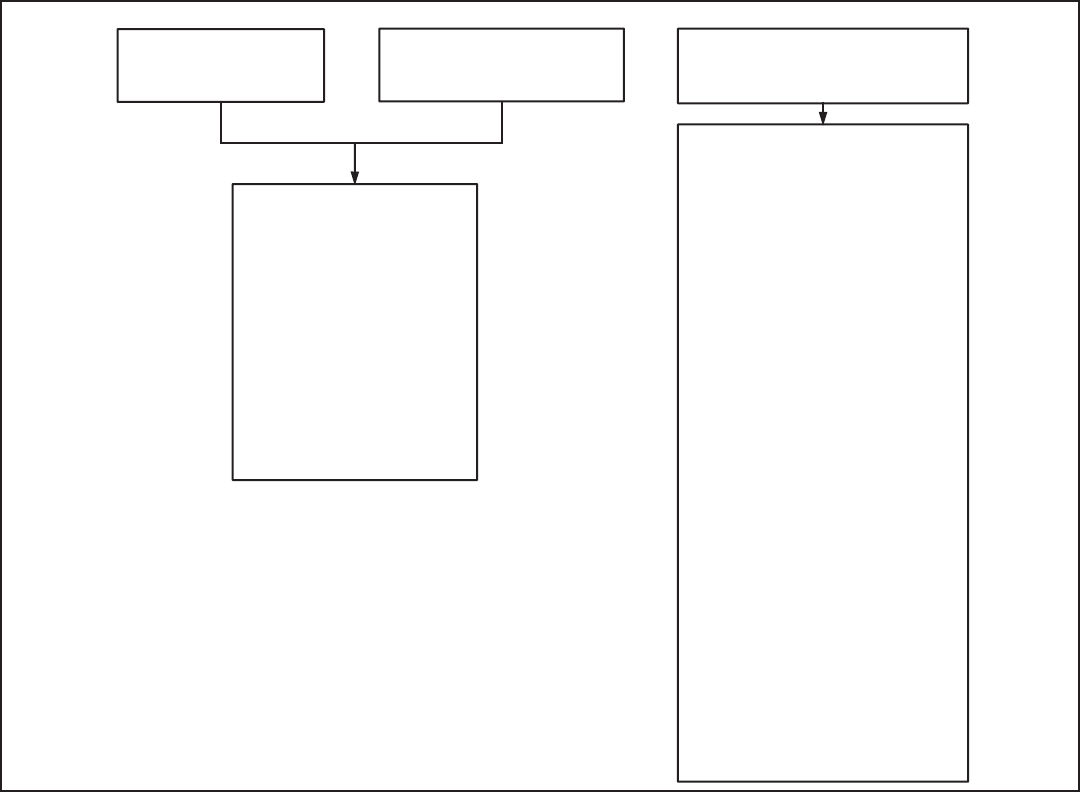

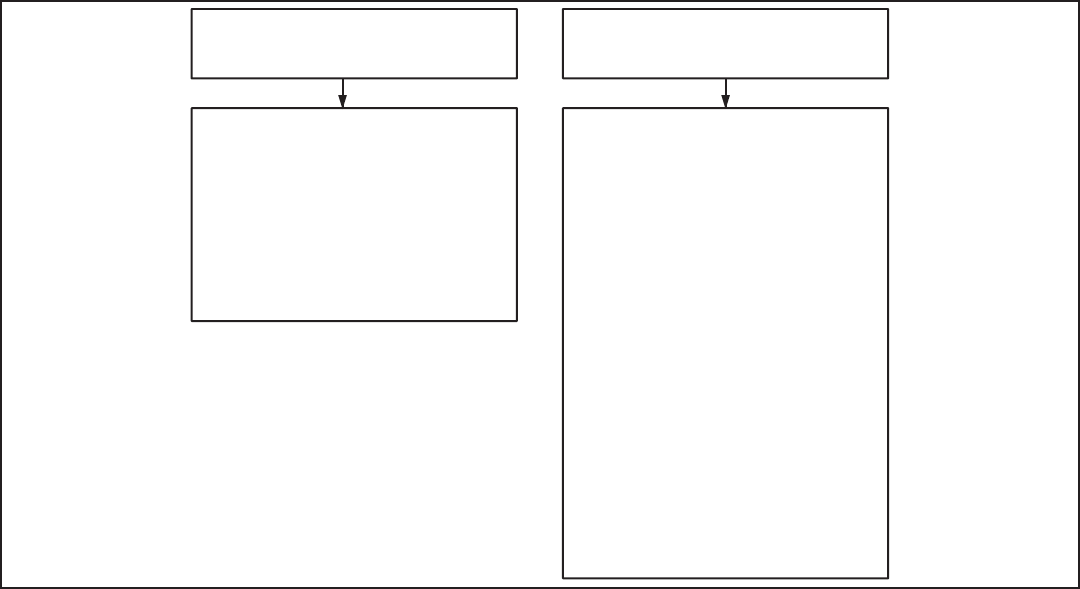

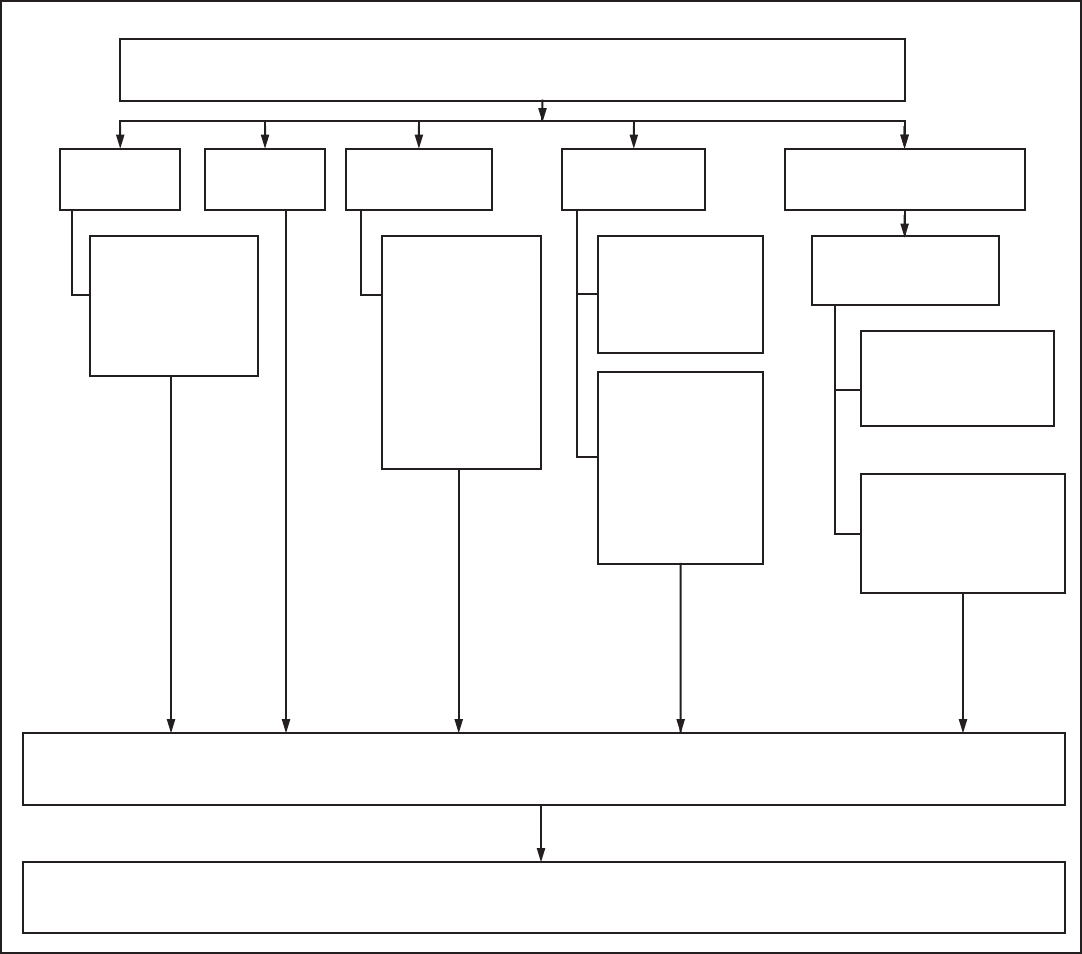

optimal method (Figure 1).

In choosing a method of contraception, the risk for human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and other sexually

transmitted diseases (STDs) also should be considered.

Although hormonal contraceptives and IUDs are highly

effective at preventing pregnancy, they do not protect against

STDs and HIV. Consistent and correct use of the male latex

condom reduces the risk for HIV infection and other STDs,

including chlamydial infection, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis

(32). On the basis of a limited number of clinical studies, when

a male condom cannot be used properly to prevent infection,

a female condom should be considered (32). All patients,

regardless of contraceptive choice, should be counseled about

the use of condoms and the risk for STDs, including HIV

infection (32). Additional information about prevention

and treatment of STDs is available from the CDC Sexually

Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines (32).

Maintaining Updated Guidance

As with any evidence-based guidance document, a key

challenge is keeping the recommendations up to date as new

scientific evidence becomes available. Working with WHO,

CDC uses the continuous identification of research evidence

(CIRE) system to ensure that WHO and CDC guidance is

based on the best available evidence and that a mechanism

is in place to update guidance when new evidence becomes

available (33). CDC will continue to work with WHO to

identify and assess all new relevant evidence and determine

whether changes in the recommendations are warranted. In

Early Release

MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62 5

most cases, U.S. SPR will follow any updates in the WHO

guidance, which typically occurs every 3–4 years (or sooner

if warranted by new data). In addition, CDC will review any

interim WHO updates for their application in the United

States. CDC also will identify and assess any new literature

for the recommendations that are not included in the WHO

guidance and will completely review U.S. SPR every 3–4

years. Updates to the guidance can be found on the U.S.

SPR website (http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/

UnintendedPregnancy/USSPR.htm).

How To Be Reasonably Certain that a

Woman Is Not Pregnant

In most cases, a detailed history provides the most accurate

assessment of pregnancy risk in a woman who is about to start

using a contraceptive method. Several criteria for assessing

pregnancy risk are listed in the recommendation that follows.

These criteria are highly accurate (i.e., a negative predictive

value of 99%–100%) in ruling out pregnancy among women

who are not pregnant (34–37). Therefore, CDC recommends

that health-care providers use these criteria to assess pregnancy

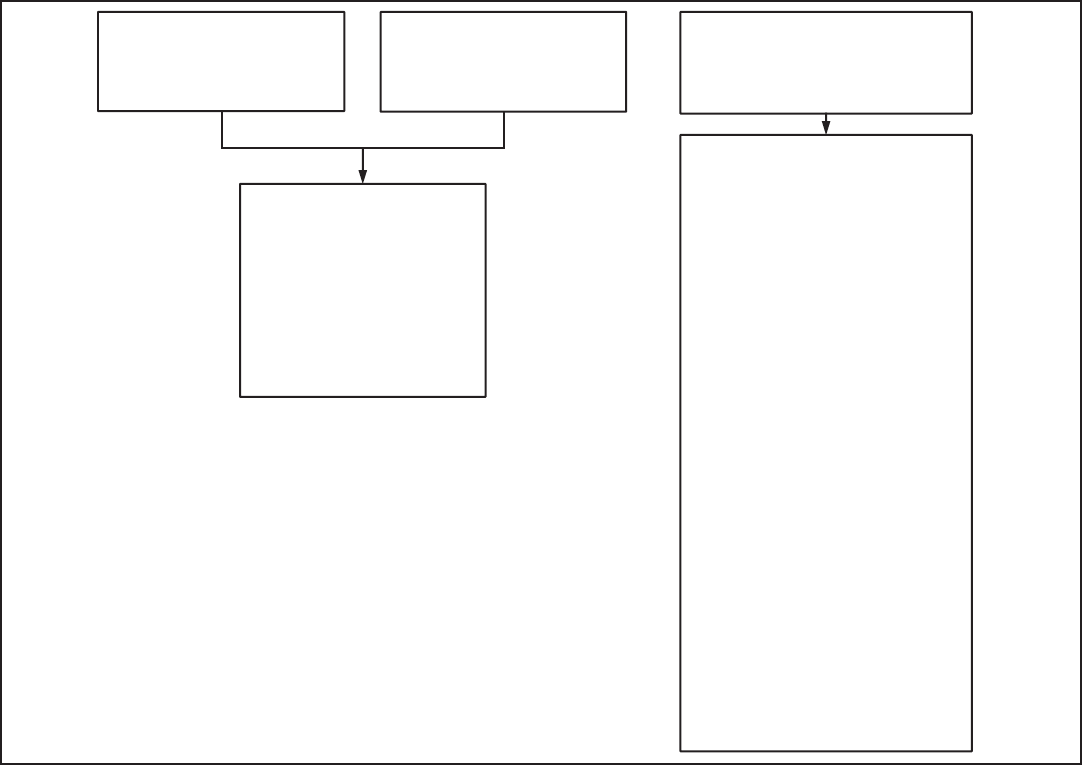

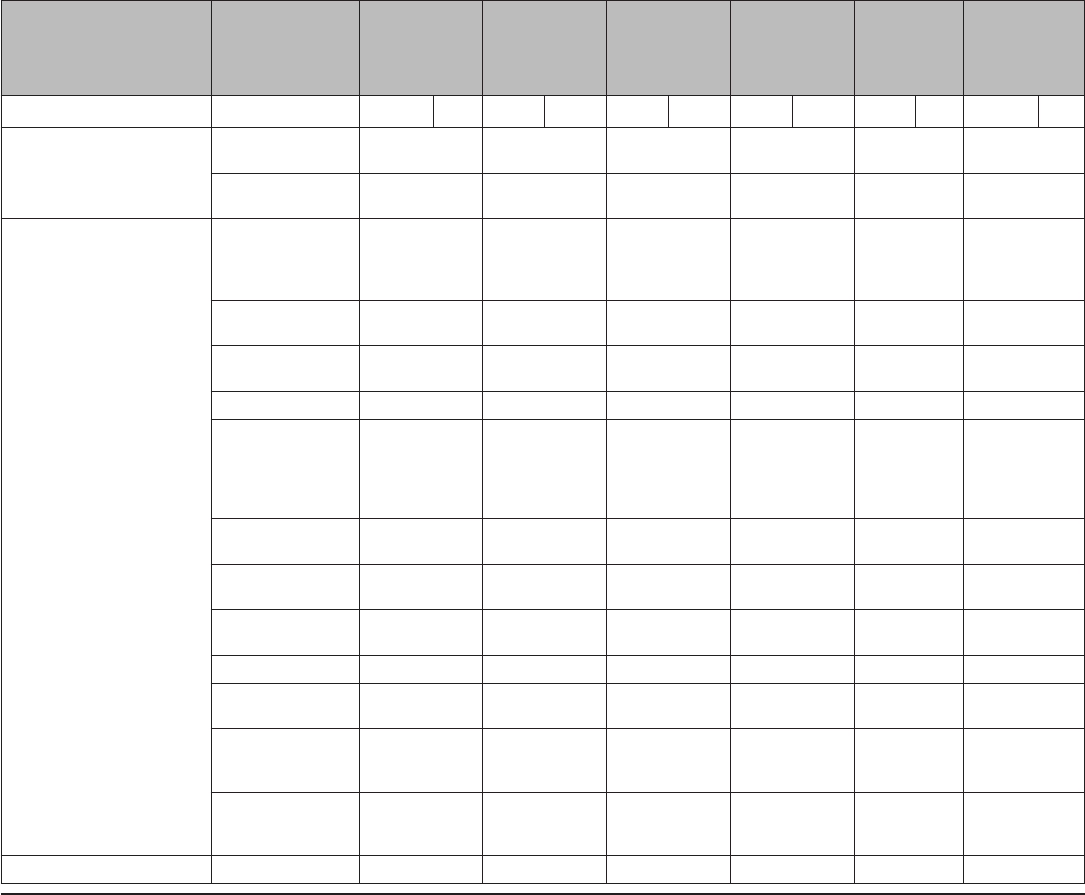

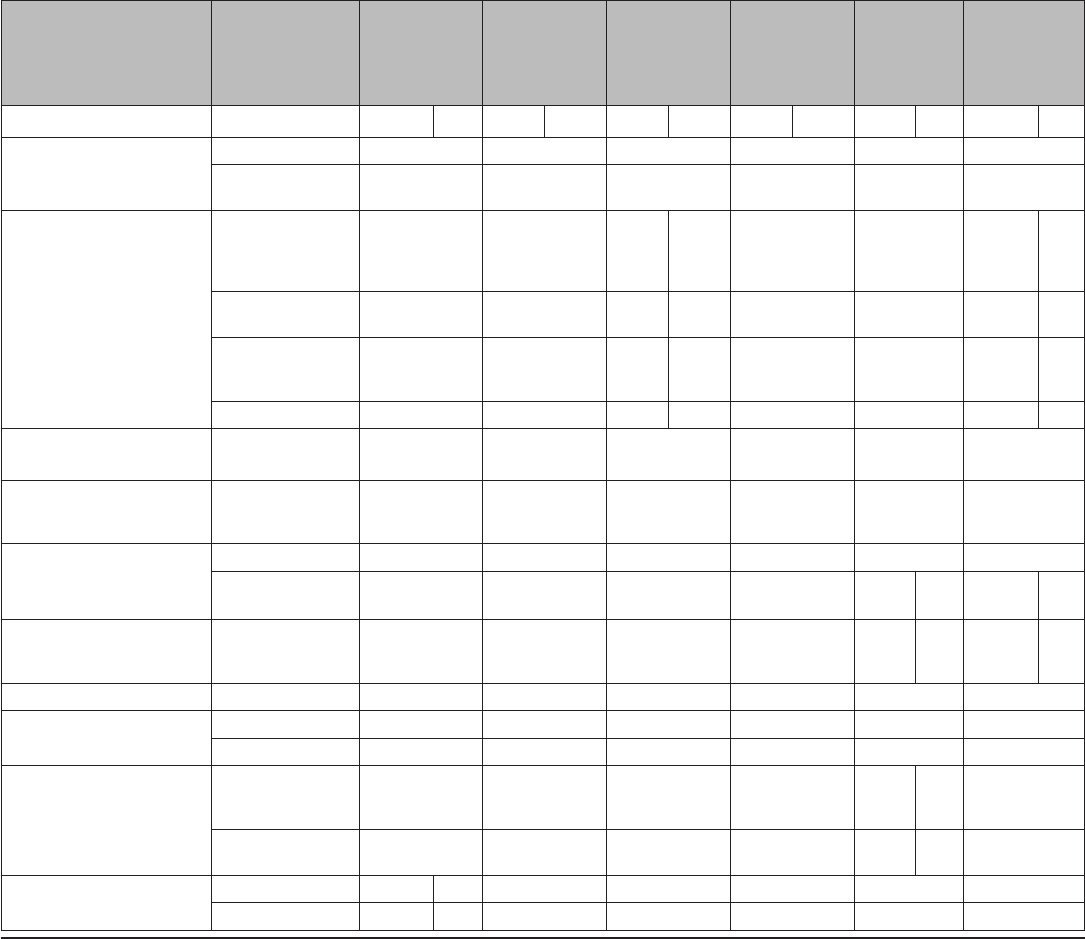

TABLE 1. Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of typical use and the first year of perfect use of

contraception and the percentage continuing use at the end of the first year — United States

Method

% of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy

within the first year of use

% of women continuing use at 1 year

§

Typical use* Perfect use

†

No method

¶

85 85 —

Spermicides** 28 18 42

Fertility awareness–based methods

††

24 — 47

Standard days method — 5 —

Two day method — 4 —

Ovulation method — 3 —

Symptothermal method — 0.4 —

Withdrawal 22 4 46

Sponge

Parous women 24 20 36

Nulliparous women 12 9 —

Condom

§§

Female 21 5 41

Male 18 2 43

Diaphragm*** 12 6 57

Combined pill and progestin-only pill 9 0.3 67

Evra patch 9 0.3 67

NuvaRing 9 0.3 67

Depo-Provera 6 0.2 56

Intrauterine devices

Paragard (copper containing) 0.8 0.6 78

Mirena (levenorgestrel releasing) 0.2 0.2 80

Implanon 0.05 0.05 84

Female sterilization 0.5 0.5 100

Male sterilization 0.15 0.10 100

Lactational amenorrhea method

†††

— — —

Source: Adapted from Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83:397–404.

* Among typical couples who initiate use of a method (not necessarily for the first time), the percentage who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first

year if they do not stop use for any other reason. Estimates of the probability of pregnancy during the first year of typical use for spermicides and the diaphragm

are taken from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) corrected for underreporting of abortion; estimates for fertility awareness-based methods,

withdrawal, the male condom, the pill and Depo-Provera are taken from the 1995 and 2002 NSFG corrected for underreporting of abortion.

†

Among couples who initiate use of a method (not necessarily for the first time) and who use it perfectly (both consistently and correctly), the percentage who

experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year if they do not stop use for any other reason.

§

Among couples attempting to avoid pregnancy, the percentage who continues to use a method for 1 year.

¶

The percentage becoming pregnant in the second and third columns are based on data from populations where contraception is not used and from women who

cease using contraception to become pregnant. Among such populations, approximately 89% become pregnant within 1 year. This estimate was lowered slightly

(to 85%) to represent the percentage who would become pregnant within 1 year among women not relying on reversible methods of contraception if they

abandoned contraception altogether.

** Foams, creams, gels, vaginal suppositories, and vaginal film.

††

The ovulation and two day methods are based on evaluation of cervical mucus. The standard days method avoids intercourse on cycle days 8–19. The symptothermal

method is a double-check method based on evaluation of cervical mucus to determine the first fertile day and evaluation of cervical mucus and temperature to

determine the last fertile day.

§§

Without spermicides.

*** With spermicidal cream or jelly.

†††

This is a highly effective, temporary method of contraception. However, to maintain in effective protection against pregnancy, another method of contraception must

be used as soon as menstruation resumes, the frequency of duration of breastfeeds is reduced, bottle feeds are introduced, or the baby reaches age 6 months.

Early Release

6 MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62

status in a woman who is about to start using contraceptives

(Box 1). If a woman meets one of these criteria (and therefore

the health-care provider can be reasonably certain that she is

not pregnant), a urine pregnancy test might be considered

in addition to these criteria (based on clinical judgment),

bearing in mind the limitations of the accuracy of pregnancy

testing. If a woman does not meet any of these criteria, then

the health-care provider cannot be reasonably certain that she

is not pregnant, even with a negative pregnancy test. Routine

pregnancy testing for every woman is not necessary.

On the basis of clinical judgment, health-care providers

might consider the addition of a urine pregnancy test; however,

they should be aware of the limitations, including accuracy

of the test relative to the time of last sexual intercourse,

recent delivery, or spontaneous or induced abortion. Routine

pregnancy testing for every woman is not necessary. If a woman

has had recent (i.e., within the last 5 days) unprotected sexual

intercourse, consider offering emergency contraception (either

a Cu-IUD or ECPs), if pregnancy is not desired.

Comments and Evidence Summary. The criteria for

determining whether a woman is pregnant depend on the

assurance that she has not ovulated within a certain amount of

time after her last menses, spontaneous or induced abortion, or

delivery. Among menstruating women, the timing of ovulation

can vary widely. During an average 28-day cycle, ovulation

generally occurs during days 9–20 (38). In addition, the

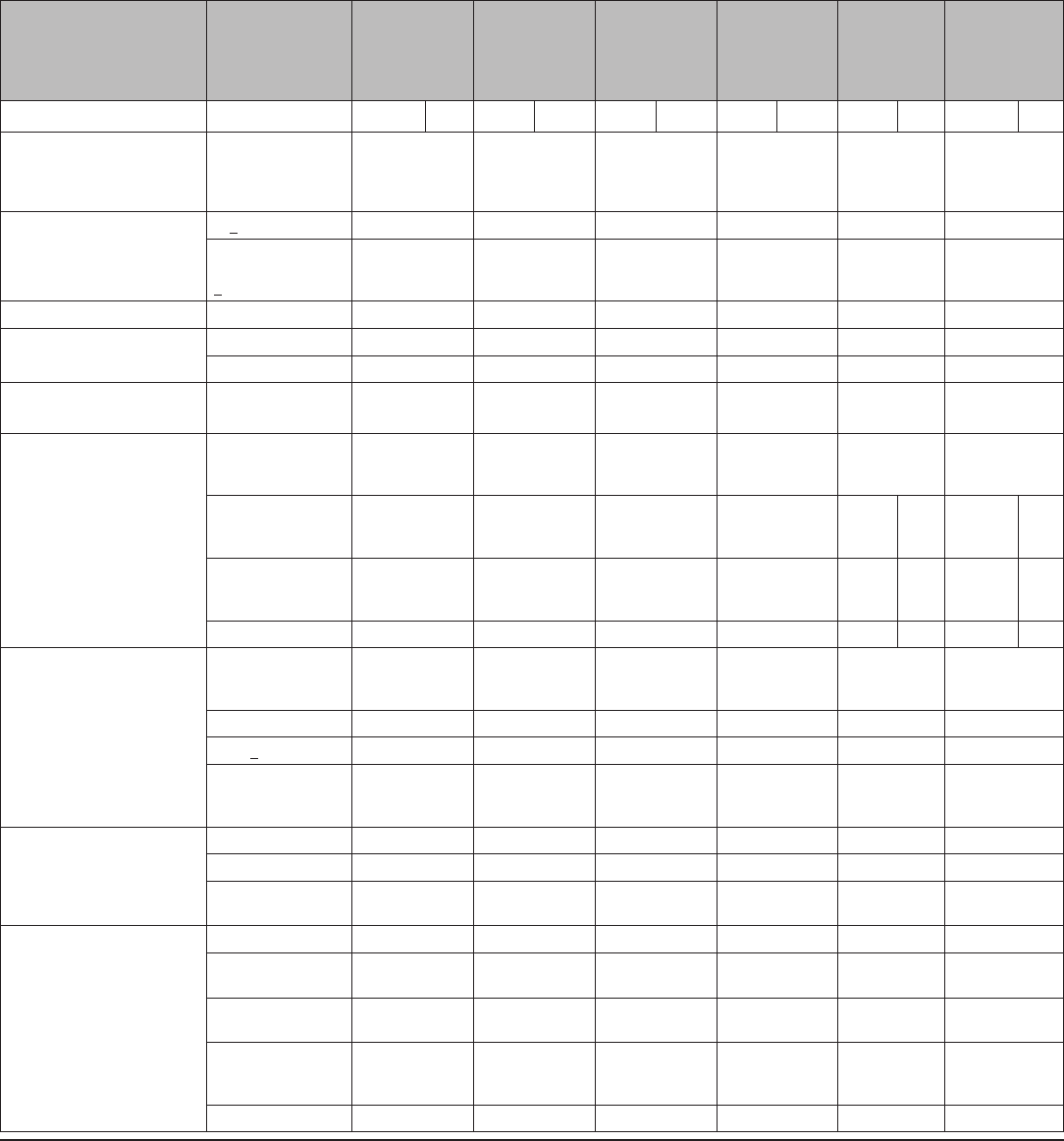

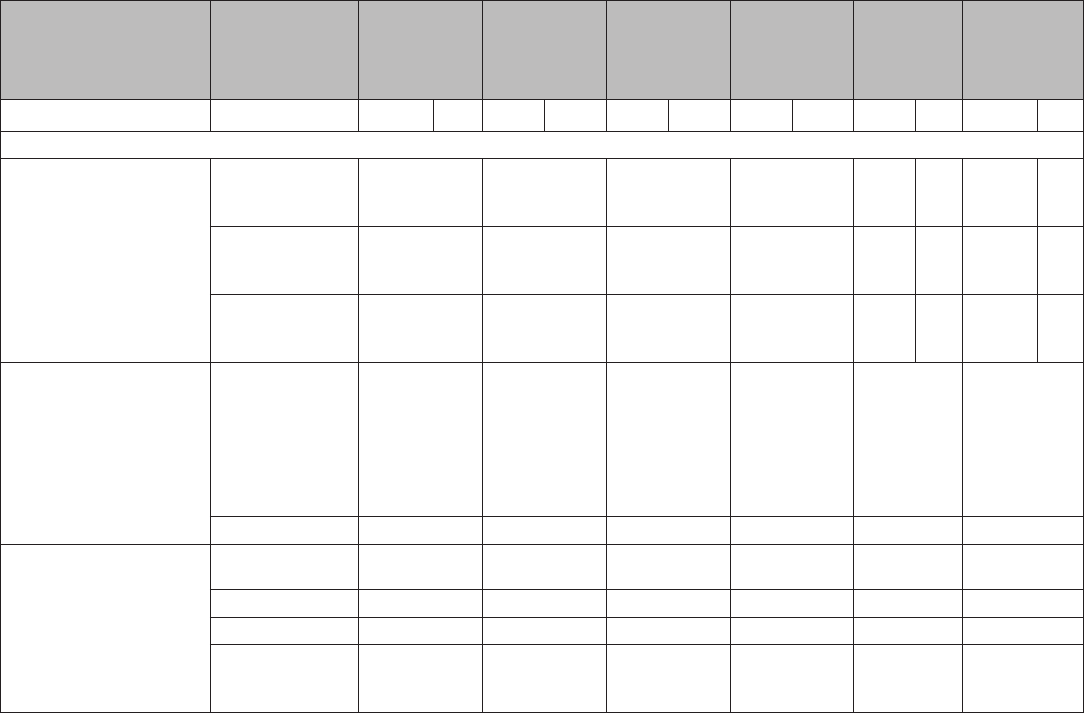

FIGURE 1. Effectiveness of family planning methods

Sources: Adapted from World Health Organization (WHO) Department of Reproductive Health and Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/

Center for Communication Programs (CCP). Knowledge for health project. Family planning: a global handbook for providers (2011 update). Baltimore, MD; Geneva,

Switzerland: CCP and WHO; 2011; and Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83:397–404.

Early Release

MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62 7

likelihood of ovulation is low from days 1–7 of the menstrual

cycle (39). After a spontaneous or an induced abortion,

ovulation can occur within 2–3 weeks and has been found

to occur as early as 8–13 days after the end of the pregnancy.

Therefore, the likelihood of ovulation is low ≤7 days after an

abortion (40–42). A recent systematic review reported that the

mean day of first ovulation among postpartum nonlactating

women occurred 45–94 days after delivery (43). In one study,

the earliest ovulation was reported at 25 days after delivery.

Among women who are within 6 months postpartum, are fully

or nearly fully breastfeeding, and are amenorrheic, the risk for

pregnancy is <2% (44).

Although pregnancy tests often are performed before

initiating contraception, the accuracy of qualitative urine

pregnancy tests varies depending on the timing of the test

relative to missed menses, recent sexual intercourse, or recent

pregnancy. The sensitivity of a pregnancy test is defined as

the concentration of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG)

at which 95% of tests are positive. Most qualitative pregnancy

tests approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) report a sensitivity of 20–25 mIU/mL in urine (45–48)

However, pregnancy detection rates can vary widely because of

differences in test sensitivity and the timing of testing relative

to missed menses (47,49). Some studies have shown that an

additional 11 days past the day of expected menses are needed

to detect 100% of pregnancies using qualitative tests (46). In

addition, pregnancy tests cannot detect a pregnancy resulting

from recent sexual intercourse. Qualitative tests also might have

positive results for several weeks after termination of pregnancy

because hCG can be present for several weeks after delivery or

abortion (spontaneous or induced) (50–52).

For contraceptive methods other than IUDs, the benefits

of starting to use a contraceptive method likely exceed any

risk, even in situations in which the health-care provider is

uncertain whether the woman is pregnant. Therefore, the

health-care provider can consider having patients start using

contraceptive methods other than IUDs at any time, with

a follow-up pregnancy test in 2–4 weeks. The risks of not

starting to use contraception should be weighed against the

risks of initiating contraception use in a woman who might

be already pregnant. Most studies have shown no increased

risk for adverse outcomes, including congenital anomalies

or neonatal or infant death, among infants exposed in utero

to COCs (53–55). Studies also have shown no increased risk

for neonatal or infant death or developmental abnormalities

among infants exposed in utero to DMPA (54,56,57).

In contrast, for women who want to begin using an IUD

(Cu-IUD or LNG-IUD), in situations in which the health-

care provider is uncertain whether the woman is pregnant, the

woman should be provided with another contraceptive method

to use until the health-care provider is reasonably certain that

she is not pregnant and can insert the IUD. Pregnancies among

women with IUDs are at higher risk for complications such as

spontaneous abortion, septic abortion, preterm delivery, and

chorioamnionitis (58).

A systematic review identified four analyses of data

from three diagnostic accuracy studies that evaluated the

performance of the criteria listed above through use of a

pregnancy checklist compared with a urine pregnancy test

conducted concurrently (12). The performance of the checklist

to diagnose or exclude pregnancy varied, with sensitivity

of 55%–100% and specificity of 39%–89%. The negative

predictive value was consistent across studies at 99%–100%;

the pregnancy checklist correctly ruled out women who were

not pregnant. One of the studies assessed the added usefulness

of signs and symptoms of pregnancy and found that these

criteria did not substantially improve the performance of the

pregnancy checklist, although the number of women with signs

and symptoms was small (34) (Level of evidence: Diagnostic

accuracy studies, fair, direct).

Intrauterine Contraception

Three IUDs are available in the United States, the Cu-IUD

and two LNG-IUDs (containing a total of either 13.5 mg

or 52 mg levonorgestrel). Fewer than 1 woman out of 100

becomes pregnant in the first year of using IUDs (with typical

use) (59). IUDs are long acting, are reversible, and can be

BOX 1. How To Be Reasonably Certain that a Woman Is Not Pregnant

A health-care provider can be reasonably certain that a

woman is not pregnant if she has no symptoms or signs

of pregnancy and meets any one of the following criteria:

• is ≤7 days after the start of normal menses

• has not had sexual intercourse since the start of last

normal menses

• has been correctly and consistently using a reliable

method of contraception

• is ≤7 days after spontaneous or induced abortion

•

is within 4 weeks postpartum

• is fully or nearly fully breastfeeding (exclusively

breastfeeding or the vast majority [≥85%] of feeds are

breastfeeds),* amenorrheic, and <6 months

postpartum

* Source: Labbok M, Perez A, Valdez V, et al. The Lactational Amenorrhea

Method (LAM): a postpartum introductory family planning method with

policy and program implications. Adv Contracept 1994;10:93–109.

Early Release

8 MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62

used by women of all ages, including adolescents, and both by

parous and nulliparous women. IUDs do not protect against

STDs; consistent and correct use of male latex condoms reduces

the risk for STDs, including HIV.

Initiation of Cu-IUDs

Timing

• TheCu-IUDcanbeinsertedatanytimeifitisreasonably

certain that the woman is not pregnant (Box 1).

• TheCu-IUDalsocanbeinsertedwithin5daysofthefirst

act of unprotected sexual intercourse as an emergency

contraceptive. If the day of ovulation can be estimated, the

Cu-IUD also can be inserted >5 days after sexual intercourse

as long as insertion does not occur >5 days after ovulation.

Need for Back-Up Contraception

• Noadditionalcontraceptive protectionisneededafter

Cu-IUD insertion.

Special Considerations

Amenorrhea (Not Postpartum)

• Timing: The Cu-IUD can be inserted at any time if it is

reasonably certain that the woman is not pregnant (Box 1).

• Need for back-up contraception: No additional contraceptive

protection is needed.

Postpartum (Including After Cesarean Section)

• Timing: The Cu-IUD can be inserted at any time postpartum,

including immediately postpartum (U.S. MEC 1 or 2) (Box 2),

if it is reasonably certain that the woman is not pregnant

(Box 1). The Cu-IUD should not be inserted in a woman with

puerperal sepsis (U.S. MEC 4).

• Need for back-up contraception: No additional

contraceptive protection is needed.

Postabortion (Spontaneous or Induced)

• Timing: The Cu-IUD can be inserted within the first

7 days, including immediately postabortion (U.S. MEC 1

for first trimester abortion and U.S. MEC 2 for second

trimester abortion). The Cu-IUD should not be inserted

immediately after septic abortion (U.S. MEC 4).

• Need for back-up contraception: No additional

contraceptive protection is needed.

Switching from Another Contraceptive Method

• Timing: The Cu-IUD can be inserted immediately if it is

reasonably certain that the woman is not pregnant (Box 1).

Waiting for her next menstrual period is unnecessary.

• Need for back-up contraception: No additional

contraceptive protection is needed.

Comments and Evidence Summary. In situations in which

the health-care provider is not reasonably certain that the

woman is not pregnant, the woman should be provided with

another contraceptive method to use until the health-care

provider can be reasonably certain that she is not pregnant

and can insert the Cu-IUD.

A systematic review identified eight studies that suggested that

timing of Cu-IUD insertion in relation to the menstrual cycle in

nonpostpartum women had little effect on long-term outcomes

(rates of continuation, removal, expulsion, or pregnancy) or on

short-term outcomes (pain at insertion, bleeding at insertion, or

immediate expulsion) (13) (Level of evidence: II-2, fair, direct).

Initiation of LNG-IUDs

Timing of LNG-IUD Insertion

• TheLNG-IUDcanbeinsertedatanytimeifitisreasonably

certain that the woman is not pregnant (Box 1).

Need for Back-Up Contraception

• IftheLNG-IUDisinsertedwithinthefirst7dayssince

menstrual bleeding started, no additional contraceptive

protection is needed.

• IftheLNG-IUDisinserted>7dayssincemenstrualbleeding

started, the woman needs to abstain from sexual intercourse

or use additional contraceptive protection for the next 7 days.

BOX 2. Categories of medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use

U.S. MEC 1 = A condition for which there is no restriction

for the use of the contraceptive method.

U.S. MEC 2 = A condition for which the advantages of

using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or

proven risks.

U.S. MEC 3 = A condition for which the theoretical or

proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the

method.

U.S. MEC 4 = A condition that represents an unacceptable

health risk if the contraceptive method is used.

Abbreviations: U.S. MEC = U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive

Use, 2010.

Source: CDC. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use.

MMWR 2010;59(No. RR-4).

Early Release

MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62 9

Special Considerations

Amenorrhea (Not Postpartum)

• Timing: The LNG-IUD can be inserted at any time if it is

reasonably certain that the woman is not pregnant (Box 1).

• Need for back-up contraception: The woman needs to

abstain from sexual intercourse or use additional

contraceptive protection for the next 7 days.

Postpartum (Including After Cesarean Section)

•

Timing: The LNG-IUD can be inserted at any time,

including immediately postpartum (U.S. MEC 1 or 2) if

it is reasonably certain that the woman is not pregnant

(Box 1). The LNG-IUD should not be inserted in a

woman with puerperal sepsis (U.S. MEC 4).

• Need for back-up contraception: If the woman is

<6 months postpartum, amenorrheic, and fully or nearly

fully breastfeeding (exclusively breastfeeding or the vast

majority [≥85%] of feeds are breastfeeds) (60), no

additional contraceptive protection is needed. Otherwise,

a woman who is ≥21 days postpartum and has not

experienced return of her menstrual cycle needs to abstain

from sexual intercourse or use additional contraceptive

protection for the next 7 days. If her menstrual cycles have

returned and it has been >7 days since menstrual bleeding

began, she needs to abstain from sexual intercourse or use

additional contraceptive protection for the next 7 days.

Postabortion (Spontaneous or Induced)

• Timing: The LNG-IUD can be inserted within the first

7 days, including immediately postabortion (U.S. MEC 1

for first-trimester abortion and U.S. MEC 2 for second-

trimester abortion). The LNG-IUD should not be inserted

immediately after a septic abortion (U.S. MEC 4).

• Need for back-up contraception: The woman needs to

abstain from sexual intercourse or use additional

contraceptive protection for the next 7 days unless the

IUD is placed at the time of a surgical abortion.

Switching from Another Contraceptive Method

• Timing: The LNG-IUD can be inserted immediately if it

is reasonably certain that the woman is not pregnant (Box 1).

Waiting for her next menstrual period is unnecessary.

• Need for back-up contraception: If it has been >7 days

since menstrual bleeding began, the woman needs to

abstain from sexual intercourse or use additional

contraceptive protection for the next 7 days.

• Switching from a Cu-IUD: If the woman has had sexual

intercourse since the start of her current menstrual cycle

and it has been >5 days since menstrual bleeding started,

theoretically, residual sperm might be in the genital tract,

which could lead to fertilization if ovulation occurs. A

health-care provider can consider providing ECPs at the

time of LNG-IUD insertion.

Comments and Evidence Summary. In situations in which

the health-care provider is uncertain whether the woman might

be pregnant, the woman should be provided with another

contraceptive method to use until the health-care provider

can be reasonably certain that she is not pregnant and can

insert the LNG-IUD. If a woman needs to use additional

contraceptive protection when switching to an LNG-IUD

from another contraceptive method, consider continuing her

previous method for 7 days after LNG-IUD insertion. No

direct evidence was found regarding the effects of inserting

LNG-IUDs on different days of the cycle on short- or long-

term outcomes (13).

Examinations and Tests Needed Before

Initiation of a Cu-IUD or an LNG-IUD

Among healthy women, few examinations or tests are needed

before initiation of an IUD (Table 2). Bimanual examination

and cervical inspection are necessary before IUD insertion. A

baseline weight and BMI measurement might be useful for

monitoring IUD users over time. If a woman has not been

screened for STDs according to STD screening guidelines,

screening can be performed at the time of insertion. Women

with known medical problems or other special conditions

might need additional examinations or tests before being

determined to be appropriate candidates for a particular

method of contraception. U.S. MEC might be useful in such

circumstances (5).

Comments and Evidence Summary. Weight (BMI):

Obese women can use IUDs (U.S. MEC 1) (5); therefore,

screening for obesity is not necessary for the safe initiation

of IUDs. However, measuring weight and calculating BMI

(weight [kg] / height [m]

2

) at baseline might be helpful for

monitoring any changes and counseling women who might

be concerned about weight change perceived to be associated

with their contraceptive method.

Bimanual examination and cervical inspection: Bimanual

examination and cervical inspection are necessary before IUD

insertion to assess uterine size and position and to detect any

cervical or uterine abnormalities that might indicate infection

or otherwise prevent IUD insertion (61,62).

STDs: Women should be routinely screened for chlamydial

infection and gonorrhea according to national screening

guidelines. The CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment

Guidelines provide information on screening eligibility, timing,

and frequency of screening and on screening for persons

Early Release

10 MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62

with risk factors (32). If STD screening guidelines have been

followed, most women do not need additional STD screening

at the time of IUD insertion. If a woman has not been screened

according to guidelines, screening can be performed at the time

of IUD insertion and insertion should not be delayed. Women

with purulent cervicitis or current chlamydial infection or

gonorrhea should not undergo IUD insertion (U.S. MEC 4).

Women who have a very high individual likelihood of STD

exposure (e.g., those with a currently infected partner) generally

should not undergo IUD insertion (U.S. MEC 3) (5). For these

women, IUD insertion should be delayed until appropriate

testing and treatment occur. A systematic review did not

identify any evidence regarding women who were screened

versus not screened for STDs before IUD insertion (14).

Although women with STDs at the time of IUD insertion

have a higher risk for PID, the overall rate of PID among all

IUD users is low (63,64).

Hemoglobin: Women with iron-deficiency anemia can use

the LNG-IUD (U.S. MEC 1) (5); therefore, screening for

anemia is not necessary for safe initiation of the LNG-IUD.

Women with iron-deficiency anemia generally can use the

Cu-IUD (U.S. MEC 2). Measurement of hemoglobin before

initiation of Cu-IUDs is not necessary because of the minimal

change in hemoglobin among women with and without anemia

using Cu-IUDs. A systematic review identified four studies that

provided direct evidence for changes in hemoglobin among

women with anemia who received Cu-IUDs (30). Evidence

from one randomized trial (65) and one prospective cohort

study (66) showed no significant changes in hemoglobin

among Cu-IUD users with anemia, whereas two prospective

cohort studies (67,68) showed a statistically significant decrease

in hemoglobin levels during 12 months of follow-up; however,

the magnitude of the decrease was small and most likely not

clinically significant. The systematic review also identified 21

studies that provided indirect evidence by examining changes

in hemoglobin among healthy women receiving Cu-IUDs

(69–89), which generally showed no clinically significant

changes in hemoglobin levels with up to 5 years of follow-up

(Level of evidence: I to II-2, fair, direct).

Liver enzymes: Women with liver disease can use the

Cu-IUD (U.S. MEC 1) (5); therefore, screening for liver

disease is not necessary for the safe initiation of the Cu-IUD.

Although women with certain liver diseases generally should

not use the LNG-IUD (U.S. MEC 3) (5), screening for liver

disease before initiation of the LNG-IUD is not necessary

because of the low prevalence of these conditions and the

high likelihood that women with liver disease already would

have had the condition diagnosed. A systematic review did

not identify any evidence regarding outcomes among women

who were screened versus not screened with liver enzyme tests

before initiation of hormonal contraceptive use (14). The

prevalence of liver disorders among women of reproductive

age is low. In 2008, among adults aged 18–44 years, the

percentage with liver disease (not further specified) was 1.0%

(90). In 2009, the incidence of acute hepatitis A, B, or C

among women was <1 per 100,000 population (91). During

1998–2007, the incidence of liver carcinoma among women

was approximately 3 per 100,000 population (92). Because

estrogen and progestins are metabolized in the liver, the use

of hormonal contraceptives among women with liver disease

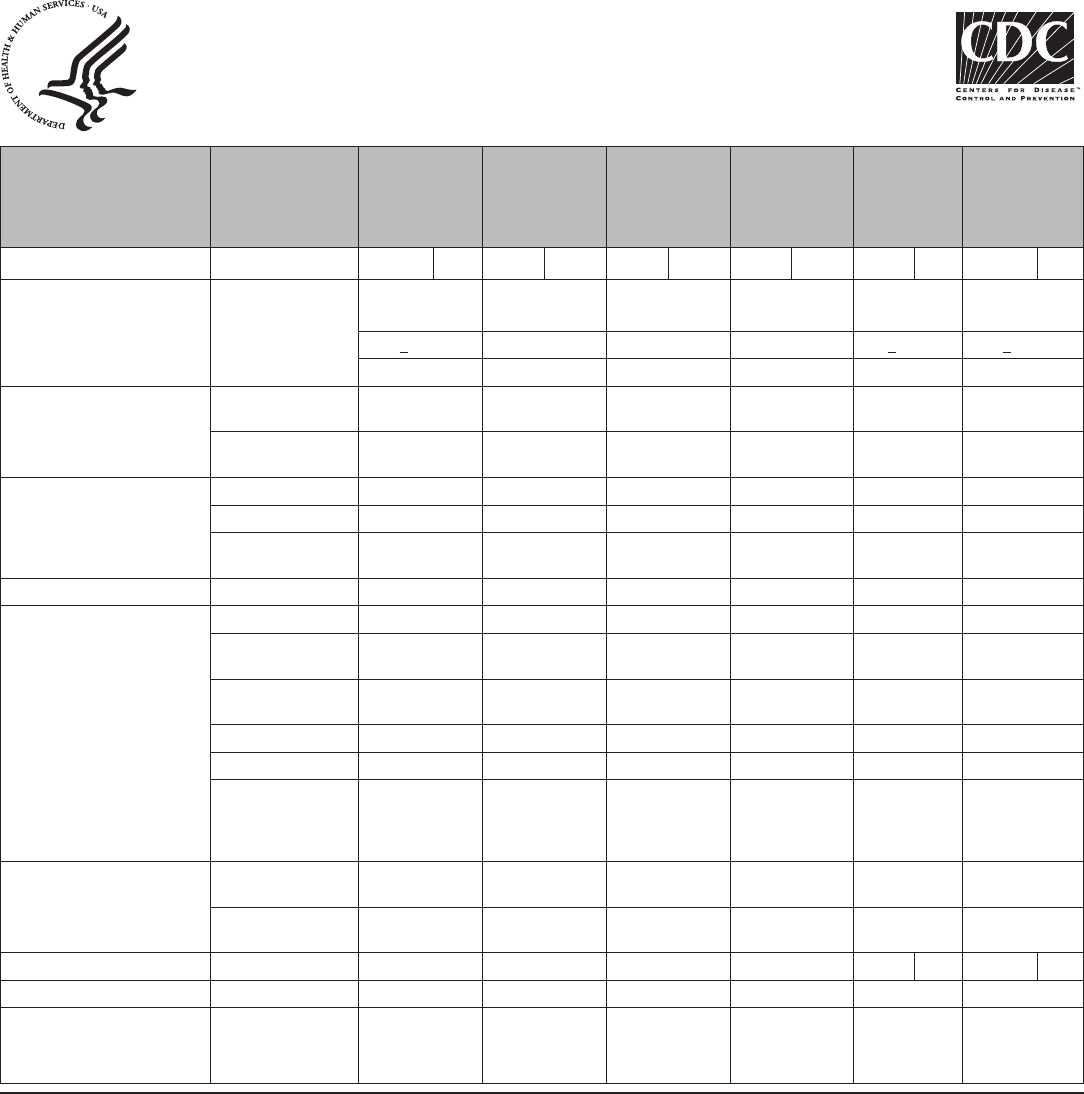

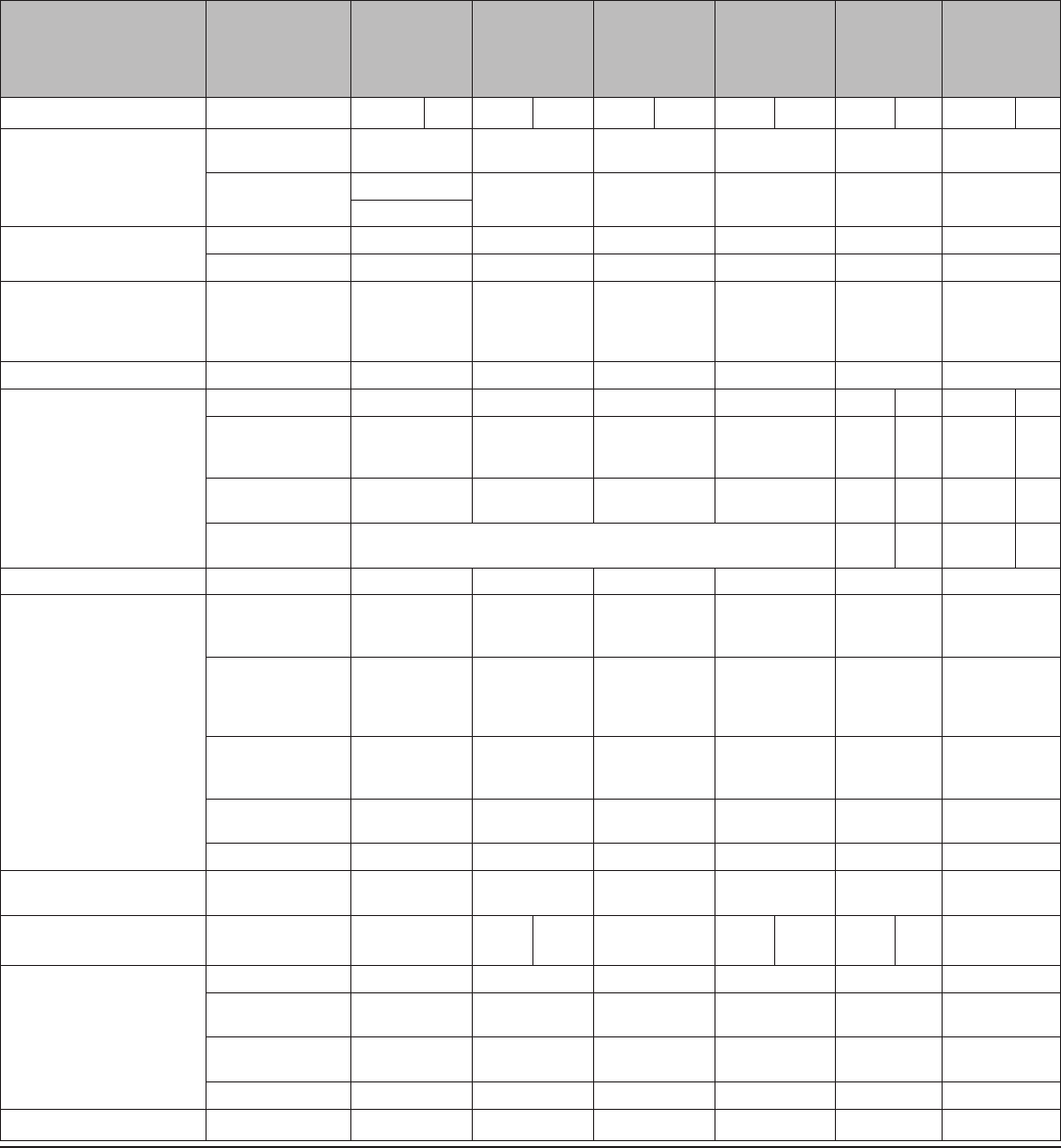

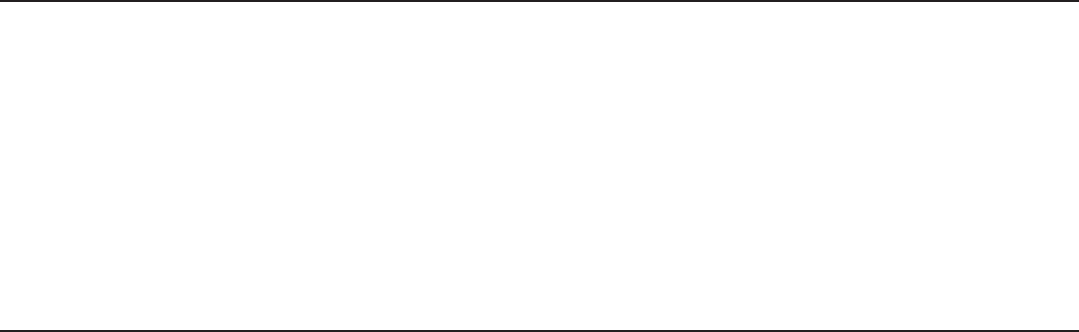

TABLE 2. Classification of examinations and tests needed before IUD

insertion

Examination or test

Class*

Copper-

containing IUD

Levonorgestrel-

releasing IUD

Examinations

Blood pressure C C

Weight (BMI) (weight [kg]/

height [m]

2

)

—

†

—

†

Clinical breast examination C C

Bimanual examination and

cervical inspection

A A

Laboratory tests

Glucose C C

Lipids C C

Liver enzymes C C

Hemoglobin C C

Thrombogenic mutations C C

Cervical cytology

(Papanicolaou smear)

C C

STD screening with

laboratory tests

—

§

—

§

HIV screening with laboratory

tests

C C

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index; HIV=human immunodeficiency virus;

IUD=intrauterine device; STD=sexually transmitted disease; U.S. MEC=U.S.

Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010.

*

Class A: essential and mandatory in all circumstances for safe and effective

use of the contraceptive method. Class B: contributes substantially to safe

and effective use, but implementation may be considered within the public

health and/or service context; the risk of not performing an examination or

test should be balanced against the benefits of making the contraceptive

method available. Class C: does not contribute substantially to safe and

effective use of the contraceptive method.

†

Weight (BMI) measurement is not needed to determine medical eligibility for any

methods of contraception because all methods can be used (U.S. MEC 1) or

generally can be used (U.S. MEC 2) among obese women (Box 2). However,

measuring weight and calculating BMI at baseline might be helpful for monitoring

any changes and counseling women who might be concerned about weight

change perceived to be associated with their contraceptive method.

§

Most women do not require additional STD screening at the time of IUD

insertion if they have already been screened according to CDC’s STD Treatment

Guidelines (available at http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment). If a woman has

not been screened according to guidelines, screening can be performed at

the time of IUD insertion, and insertion should not be delayed. Women with

purulent cervicitis or current chlamydial infection or gonorrhea should not

undergo IUD insertion (U.S. MEC 4). Women who have a very high individual

likelihood of STD exposure (e.g., those with a currently infected partner)

generally should not undergo IUD insertion (U.S. MEC 3). For these women,

IUD insertion should be delayed until appropriate testing and treatment occur.

Early Release

MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62 11

might, theoretically, be a concern. The use of hormonal

contraceptives, specifically COCs and POPs, does not affect

disease progression or severity in women with hepatitis,

cirrhosis, or benign focal nodular hyperplasia (93,94), although

evidence is limited, and no evidence exists for the LNG-IUD.

Clinical breast examination: Women with breast disease

can use the Cu-IUD (U.S. MEC 1) (5); therefore, screening

for breast disease is not necessary for the safe initiation of

the Cu-IUD. Although women with current breast cancer

should not use the LNG-IUD (U.S. MEC 4) (5), screening

asymptomatic women with a clinical breast examination

before inserting an IUD is not necessary because of the low

prevalence of breast cancer among women of reproductive

age. A systematic review did not identify any evidence

regarding outcomes among women who were screened versus

not screened with a breast examination before initiation of

hormonal contraceptives (15). The incidence of breast cancer

among women of reproductive age in the United States is low.

In 2009, the incidence of breast cancer among women aged

20–49 years was approximately 72 per 100,000 women (95).

Cervical cytology: Although women with cervical cancer

should not undergo IUD insertion (U.S. MEC 4) (5),

screening asymptomatic women with cervical cytology before

IUD insertion is not necessary because of the high rates of

cervical screening, low incidence of cervical cancer in the

United States, and high likelihood that a woman with cervical

cancer already would have had the condition diagnosed. A

systematic review did not identify any evidence regarding

outcomes among women who were screened versus not

screened with cervical cytology before initiation of IUDs (14).

Cervical cancer is rare in the United States, with an incidence

rate of 8.1 per 100,000 women per year during 2004–2008

(95). The incidence and mortality rates from cervical cancer

have declined dramatically in the United States, largely because

of cervical cytology screening (96). Overall screening rates for

cervical cancer in the United States are high; among women

aged 22–30 years, approximately 87% reported having cervical

cytology screening within the last 3 years (97).

HIV screening: Although women with acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) who are not clinically

well should generally not undergo IUD insertion (U.S. MEC 3)

(5), HIV screening is not necessary before IUD insertion

because of the high likelihood that a woman in the United

States with such an advanced stage of disease already would

have had the condition diagnosed. A systematic review did

not identify any evidence regarding outcomes among women

who were screened versus not screened for HIV infection

before IUD insertion (14). Limited evidence suggests that

IUDs are not associated with disease progression, increased

infection, or other adverse health effects among women with

HIV infection (98).

Other screening: Women with hypertension, diabetes,

hyperlipidemia, or thrombogenic mutations can use

(U.S. MEC 1) or generally can use (U.S. MEC 2) IUDs (5).

Therefore, screening for these conditions is not necessary for

the safe initiation of IUDs.

Provision of Prophylactic Antibiotics at the

Time of IUD Insertion

• Prophylacticantibioticsaregenerallynotrecommended

for Cu-IUD or LNG-IUD insertion.

Comments and Evidence Summary. Theoretically,

IUD insertion could induce bacterial spread and lead to

complications such as PID or infective endocarditis. A

metaanalysis was conducted of randomized controlled

trials examining antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo or

no treatment for IUD insertion (99). Use of prophylaxis

reduced the frequency of unscheduled return visits but did not

significantly reduce the incidence of PID or premature IUD

discontinuation. Although the risk for PID was higher within

the first 20 days after insertion, the incidence of PID was low

among all women who had IUDs inserted (63). In addition,

the American Heart Association recommends that the use of

prophylactic antibiotics solely to prevent infective endocarditis

is not needed for genitourinary procedures (100). Studies have

not demonstrated a conclusive link between genitourinary

procedures and infective endocarditis or a preventive benefit

of prophylactic antibiotics during such procedures (100).

Routine Follow-Up After IUD Insertion

These recommendations address when routine follow-up is

needed for safe and effective continued use of contraception

for healthy women. The recommendations refer to general

situations and might vary for different users and different

situations. Specific populations that might benefit from more

frequent follow-up visits include adolescents, persons with

certain medical conditions or characteristics, and persons with

multiple medical conditions.

• Adviseawomantoreturnatanytimetodiscusssideeffectsor

other problems, if she wants to change the method being used,

and when it is time to remove or replace the contraceptive

method. No routine follow-up visit is required.

• Atotherroutinevisits,health-careproviderswhoseeIUD

users should do the following:

– Assess the woman’s satisfaction with her contraceptive

method and whether she has any concerns about

method use.

Early Release

12 MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62

– Assess any changes in health status, including

medications, that would change the appropriateness of

the IUD for safe and effective continued use on the

basis of U.S. MEC (e.g., category 3 and 4 conditions

and characteristics).

– Consider performing an examination to check for the

presence of the IUD strings.

– Consider assessing weight changes and counseling women

who are concerned about weight changes perceived to be

associated with their contraceptive method.

Comments and Evidence Summary. Evidence from a

systematic review about the effect of a specific follow-up visit

schedule on IUD continuation is very limited and of poor

quality. The evidence did not suggest that greater frequency of

visits or earlier timing of the first follow-up visit after insertion

improves continuation of use (16) (Level of evidence: II-2,

poor, direct). Evidence from four studies from a systematic

review on the incidence of PID among IUD initiators, or

IUD removal as a result of PID, suggested that the incidence

of PID did not differ between women using Cu-IUDs and

those using DMPA, COCs, or LNG-IUDs (17) (Level of

evidence: I to II-2, good, indirect). Evidence on the timing of

PID after IUD insertion is mixed. Although the rate of PID

was generally low, the largest study suggested that the rate of

PID was significantly higher in the first 20 days after insertion

(63) (Level of evidence: I to II-3, good to poor, indirect).

Bleeding Irregularities with Cu-IUD Use

• BeforeCu-IUDinsertion, providecounselingabout

potential changes in bleeding patterns during Cu-IUD

use. Unscheduled spotting or light bleeding, as well as

heavy or prolonged bleeding, is common during the first

3–6 months of Cu-IUD use, is generally not harmful,

and decreases with continued Cu-IUD use.

• Ifclinicallyindicated,consideranunderlyinggynecological

problem, such as Cu-IUD displacement, an STD,

pregnancy, or new pathologic uterine conditions (e.g.,

polyps or fibroids), especially in women who have already

been using the Cu-IUD for a few months or longer and

who have developed a new onset of heavy or prolonged

bleeding. If an underlying gynecological problem is found,

treat the condition or refer for care.

• Ifanunderlyinggynecologicalproblemisnotfoundand

the woman requests treatment, the following treatment

option can be considered during days of bleeding:

– Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for

short-term treatment (5–7 days)

• Ifbleedingpersistsandthewomanfindsitunacceptable,

counsel her on alternative contraceptive methods, and

offer another method if it is desired.

Comments and Evidence Summary. During contraceptive

counseling and before insertion of the Cu-IUD, information

about common side effects such as unscheduled spotting or

light bleeding or heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding,

especially during the first 3–6 months of use, should be

discussed (70). These bleeding irregularities are generally

not harmful. Enhanced counseling about expected bleeding

patterns and reassurance that bleeding irregularities are

generally not harmful has been shown to reduce method

discontinuation in clinical trials with other contraceptives (i.e.,

DMPA) (101,102).

Evidence is limited on specific drugs, doses, and durations

of use for effective treatments for bleeding irregularities with

Cu-IUD use; therefore, although this document includes

general recommendations for treatments to consider, evidence

for specific regimens is lacking.

A systematic review identified 11 articles that examined

various therapeutic treatments for heavy menstrual bleeding,

prolonged menstrual bleeding, or both among women using

Cu-IUDs (18). Nine studies examined the use of various oral

NSAIDs for the treatment of heavy or prolonged menstrual

bleeding among Cu-IUD users and compared them to either

a placebo or a baseline cycle. Three of these trials examined

the use of indomethacin (103–105), another three examined

mefenamic acid (106–108), and another three examined

flufenamic acid (103,104,109). Other NSAIDs used in the

reported trials included alclofenac (103,104), suprofen (110),

and diclofenac sodium (111). All but one NSAID study (107)

demonstrated statistically significant or notable reductions in

mean total menstrual blood loss with NSAID use. One study

among 19 Cu-IUD users with heavy bleeding suggested that

treatment with oral tranexamic acid can significantly reduce

mean blood loss during treatment compared with placebo

(111). Data regarding the overall safety of tranexamic acid

are limited; an FDA warning states that tranexamic acid

is contraindicated in women with active thromboembolic

disease or with a history or intrinsic risk for thrombosis

or thromboembolism (112,113). Treatment with aspirin

demonstrated no statistically significant change in mean blood

loss among women whose pretreatment menstrual blood loss

was >80 mL or 60–80 mL; treatment resulted in a significant

increase among women whose pretreatment menstrual

blood loss was <60 mL (114). One study examined the use

of a synthetic form of vasopressin, intranasal desmopressin

(300

µg/day), for the first 5 days of menses for three treatment

cycles and found a significant reduction in mean blood loss

Early Release

MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62 13

compared with baseline (106) (Level of evidence: I to II-3,

poor to fair, direct). Only one small study examined treatment

of spotting with three separate NSAIDs and did not observe

improvements in spotting in any of the groups (103) (Level

of evidence: I, poor, direct).

Bleeding Irregularities (Including

Amenorrhea) with LNG-IUD Use

• Before LNG-IUD insertion, providecounselingabout

potential changes in bleeding patterns during LNG-IUD

use. Unscheduled spotting or light bleeding is expected

during the first 3–6 months of LNG-IUD use, is generally

not harmful, and decreases with continued LNG-IUD

use. Over time, bleeding generally decreases with LNG-

IUD use, and many women experience only light

menstrual bleeding or amenorrhea. Heavy or prolonged

bleeding, either unscheduled or menstrual, is uncommon

during LNG-IUD use.

Irregular Bleeding (Spotting, Light Bleeding, or

Heavy or Prolonged Bleeding)

• Ifclinicallyindicated,consideranunderlyinggynecological

problem, such as LNG-IUD displacement, an STD,

pregnancy, or new pathologic uterine conditions (e.g.,

polyps or fibroids). If an underlying gynecological problem

is found, treat the condition or refer for care.

• Ifbleedingpersistsandthewomanfindsitunacceptable,

counsel her on alternative contraceptive methods, and

offer another method if it is desired.

Amenorrhea

• Amenorrheadoesnotrequire any medical treatment.

Provide reassurance.

– If a woman’s regular bleeding pattern changes abruptly

to amenorrhea, consider ruling out pregnancy if

clinically indicated.

• Ifamenorrheapersistsandthewomanfindsitunacceptable,

counsel her on alternative contraceptive methods, and

offer another method if it is desired

Comments and Evidence Summary. During contraceptive

counseling and before insertion of the LNG-IUD, information

about common side effects such as unscheduled spotting

or light bleeding, especially during the first 3–6 months of

use, should be discussed. Approximately half of LNG-IUD

users are likely to experience amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea

by 2 years of use (115). These bleeding irregularities are

generally not harmful. Enhanced counseling about expected

bleeding patterns and reassurance that bleeding irregularities

are generally not harmful has been shown to reduce method

discontinuation in clinical trials with other hormonal

contraceptives (i.e., DMPA) (101,102). No direct evidence

was found regarding therapeutic treatments for bleeding

irregularities during LNG-IUD use.

Management of the IUD when a Cu-IUD or

an LNG-IUD User Is Found To Have PID

• TreatthePIDaccordingtotheCDCSexually Transmitted

Diseases Treatment Guidelines (32).

• ProvidecomprehensivemanagementforSTDs,including

counseling about condom use.

• TheIUDdoesnotneedtoberemovedimmediatelyifthe

woman needs ongoing contraception.

• Reassess the woman in 48–72hours.Ifnoclinical

improvement occurs, continue antibiotics and consider

removal of the IUD.

• If the woman wantstodiscontinue use, removetheIUD

sometime after antibiotics have been started to avoid the potential

risk for bacterial spread resulting from the removal procedure.

• If the IUD is removed,considerECPs if appropriate.

Counsel the woman on alternative contraceptive methods,

and offer another method if it is desired.

• AsummaryofIUDmanagementinwomenwithPIDis

provided (Appendix F).

Comments and Evidence Summary. Treatment outcomes

do not generally differ between women with PID who retain

the IUD and those who have the IUD removed; however,

appropriate antibiotic treatment and close clinical follow-up

are necessary.

A systematic review identified four studies that included

women using copper or nonhormonal IUDs who developed

PID and compared outcomes between women who had the

IUD removed or did not (19). One randomized trial showed

that women with IUDs removed had longer hospitalizations

than those who did not, although no differences in PID

recurrences or subsequent pregnancies were observed (116).

Another randomized trial showed no differences in laboratory

findings among women who removed the IUD compared

with those who did not (117). One prospective cohort study

showed no differences in clinical or laboratory findings during

hospitalization; however, the IUD removal group had longer

hospitalizations (118). One randomized trial showed that

the rate of recovery for most clinical signs and symptoms

was higher among women who had the IUD removed than

among women who did not (119). No evidence was found

regarding women using LNG-IUDs (Level of evidence: I to

II-2, fair, direct).

Early Release

14 MMWR / June 14, 2013 / Vol. 62

Management of the IUD when a Cu-IUD or

an LNG-IUD User Is Found To Be Pregnant

• Evaluateforpossibleectopicpregnancy.

• Advisethewomanthatshehas an increased risk for

spontaneous abortion (including septic abortion that

might be life threatening) and of preterm delivery if the

IUD is left in place. The removal of the IUD reduces these

risks but might not decrease the risk to the baseline level

of a pregnancy without an IUD.

– If she does not want to continue the pregnancy, counsel

her about options.

– If she wants continue the pregnancy, advise her to seek

care promptly if she has heavy bleeding, cramping, pain,

abnormal vaginal discharge, or fever.

IUD Strings Are Visible or Can Be Retrieved Safely

from the Cervical Canal

• AdvisethewomanthattheIUDshouldberemovedas

soon as possible.

– If the IUD is to be removed, remove it by pulling on

the strings gently.

– Advise the woman that she should return promptly if

she has heavy bleeding, cramping, pain, abnormal

vaginal discharge, or fever.

• IfshechoosestokeeptheIUD,advisehertoseekcare

promptly if she has heavy bleeding, cramping, pain,

abnormal vaginal discharge, or fever.

IUD Strings Are Not Visible and Cannot Be

Retrieved Safely

• If ultrasonography is available, consider performing or

referring for ultrasound examination to determine the

location of the IUD. If the IUD cannot be located, it might

have been expelled or have perforated the uterine wall.

• IfultrasonographyisnotpossibleortheIUDisdetermined

by ultrasound to be inside the uterus, advise the woman

to seek care promptly if she has heavy bleeding, cramping,

pain, abnormal vaginal discharge, or fever.

Comments and Evidence Summary. Removing the IUD

improves the pregnancy outcome if the IUD strings are visible

or the device can be retrieved safely from the cervical canal.

Risks for spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and infection

are substantial if the IUD is left in place.

Theoretically, the fetus might be affected by hormonal