McNair Scholars Research Journal McNair Scholars Research Journal

Volume 4 Article 5

2012

A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction in English A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction in English

Danielle Lawson

Eastern Michigan University

Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Lawson, Danielle (2012) "A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction in English,"

McNair Scholars

Research Journal

: Vol. 4 , Article 5.

Available at: https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol4/iss1/5

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the McNair Scholars Program at DigitalCommons@EMU.

It has been accepted for inclusion in McNair Scholars Research Journal by an authorized editor of

DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected].

A MORPHO-SYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTRACTION IN ENGLISH

Danielle Lawson

Dr. T. Daniel Seely, Mentor

ABSTRACT

What’s contraction? Contraction is the process of taking two free morphemes and

making one bound in order to create one morpheme. In short: two words are joined into one. To

the native English speaker, contracted and non-contracted forms are semantically equivalent.

However, there are certain instances where contraction is not permitted. For example, the

sentence, “I’m happy, but she’s not,” is perfectly grammatical, but “*I’m not happy, but she’s,”

is ungrammatical. Why should this be? Although the contracted and non-contracted forms are

semantically equivalent, they differ structurally. To answer the question of what conditions allow

for contraction, existing arguments on the topic will be discussed. However, the problem with

these arguments is that they are too broad or they do not cover all types of contraction. This

proposal offers a solution by claiming that there are two procedures for contraction in English. In

this proposal, the contracting morphemes determine which procedure is performed. In finite

contraction, the morphemes bear tense. This means that the bound morphemes must contract and

attach themselves, as prefixes, to hosts located on the right of the morphemes. However, in non-

finite contraction, the morphemes are tenseless. As a result, they must contract and attach

themselves, as suffixes, to hosts located on the left of the morphemes.

INTRODUCTION

This paper presents a new analysis of certain types of contraction in English. We will

examine previous explanations of the conditions that allow for contraction and reveal problems

1

Lawson: A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction

Published by DigitalCommons@EMU, 2012

with them. The central problem with the previous arguments is that they inaccurately describe

the phenomenon, or they do not cover all types of contraction. The proposal presented in this

paper offers a solution by claiming that there are two procedures for contraction. The first

procedure deals with morphemes that bear tense, which will be referred to as finite contraction in

this paper. In this case, the contracted morpheme attaches itself to its host, located on the right of

the morpheme, as a prefix. The second procedure deals with morphemes that are tenseless, which

will be referred to as non-finite contraction. In this procedure, the contracted morpheme attaches

itself to its host, located on the left of the morpheme, as a suffix. Overall, we will argue that the

previous analyses are either too broad or too restrictive. The alternative account we have

developed is shown to have both greater empirical coverage and interesting implications for the

nature of clausal structure, and syntactic theory, more generally.

BACKGROUND

Contraction is an optional procedure where a once-free morpheme becomes “bound,”

finding a host to which it attaches itself. In the following example, “She’s studying,” the copula

has been reduced from “is” to “s” and as a result, the copula appears to change from a free

morpheme to a bound morpheme. The contracted morpheme then locates a host to which it

attaches itself. The traditional view of contraction is represented by the orthographic system in

English. Using the example given above, this view states that when the copula is reduced, it

attaches to its host (she), located to the left of the morpheme, and the apostrophe is a

“placeholder” for the piece of the contracted word that is reduced. However, there is another

influential analysis of contraction proposed by linguist Joan Bresnan (1971). Bresnan argues that,

in tensed be-contraction, “be” is actually contracting and attaching itself, as a prefix, to a host

2

McNair Scholars Research Journal, Vol. 4 [2012], Art. 5

https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol4/iss1/5

located on the right of the morpheme. The orthographic system gives the illusion that be-

contraction is contracting to the left when in reality the opposite is occurring. (cf Boeckx, 2000)

This argument is plausible because in English, when tense appears as a bound morpheme, as in

affix hopping, it always lowers and attaches itself to the verb, located on the right of the

morpheme, as illustrated in example (1).

(1) She jumped.

In this example, past tense “-ed” is unable to stand alone in “T”. Because “-ed” is

a bound morpheme, it must lower onto the verb so that it may be expressed.

A second group of countries contributed a substantial number of Arab Americans,

but not as many as Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, are Egypt, Yemen, and Iraq (McCarus

1994). For Bresnan (1971), the reduced tense-bearing auxiliary verb contracts to an overt

category to the immediate right of the auxiliary. Bresnan’s analysis predicts that if there is not an

overt category to the right of tensed “be”, contraction will not be possible because there is no

appropriate host. The example below indicates that this prediction is correct.

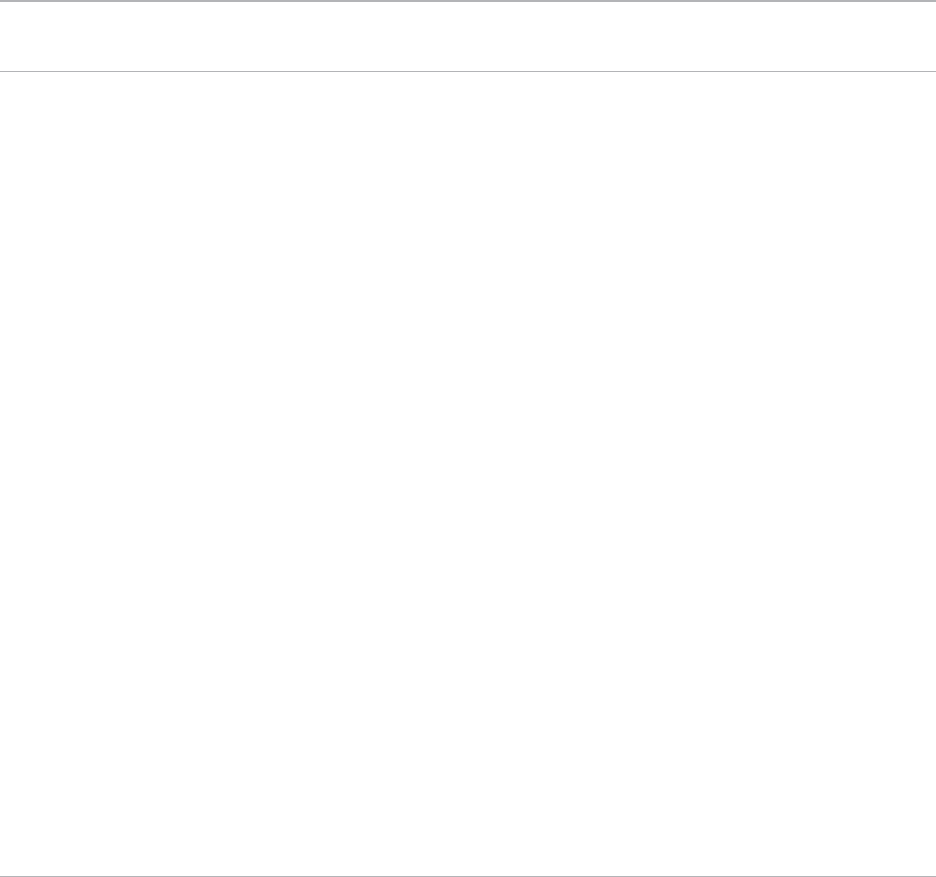

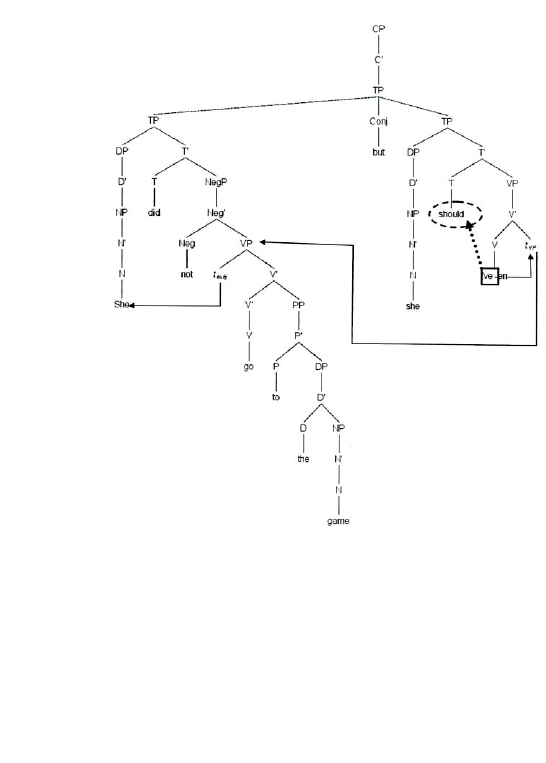

(2) I [‘m/am] not (happy), but she [*‘s/is].

In example (2), under the traditional view, contraction should be permitted because there

is an overt host (she) on the left of the reduced copula; however, this sentence is ungrammatical.

On the other hand, if we adopt Bresnan’s analysis, which states that tensed be-contraction must

(1)

(2)

3

Lawson: A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction

Published by DigitalCommons@EMU, 2012

have an overt host on the right of the morpheme in order for contraction to occur, example (2) is

correctly predicted to be ungrammatical because “‘s” has no overt host on the right.

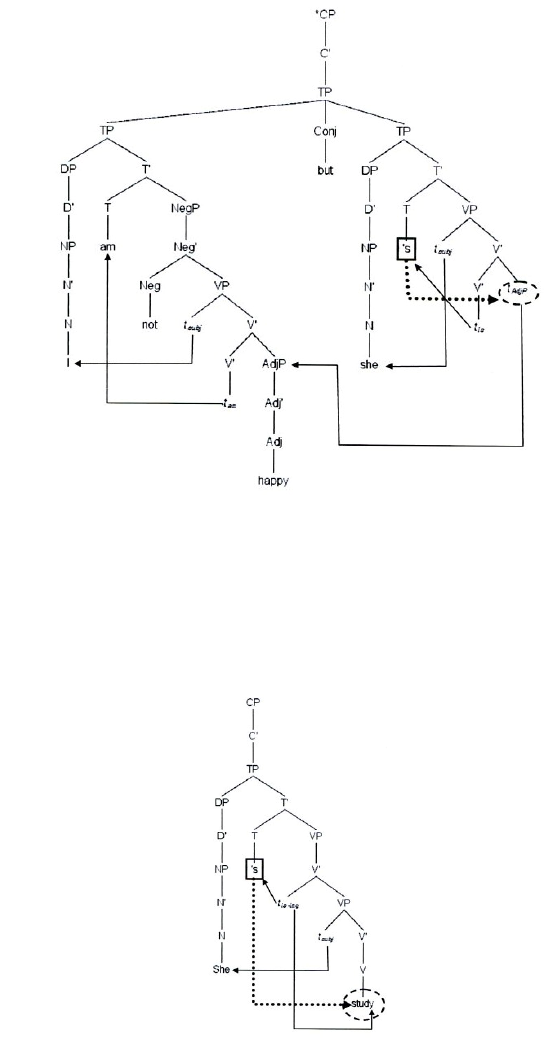

(3) She [‘s/is] studying.

In example (3), there is an overt element to the right (studying), which serves as a host for

tensed “be,” and the example is well-formed, as predicted.

(4) I [‘m/am] happy, but she [‘s/is] not.

(3)

4

McNair Scholars Research Journal, Vol. 4 [2012], Art. 5

https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol4/iss1/5

In example (4), tense, which is being represented by “‘s,” is contracting onto “not,”

which is located directly to the right of the “T” position.

At first glance, Bresnan’s analysis seems counter-intuitive, but as previously stated, in

English, when tense appears as a bound morpheme, it lowers and attaches itself to a host located

on the right of the morpheme. It is the orthographic system that misleads us into thinking that

when tensed “be” contracts, it attaches to a host on the left, when in reality it is contracting and

attaching itself to a host located on the right. However, Bresnan’s analysis is not without its own

difficulties, which is something we will reveal in section 4. First, we present more data in

support of Bresnan’s analysis.

Expanding Bresnan’s Analysis

Although Bresnan’s analysis only deals with tensed be-contraction, it can be applied to

some modals as well as to some complementizers. In examples (5) – (9), other tense bearing

elements behave the same as tensed “be”; that is, if the tense-bearing verbal element is not

followed by an overt category, contraction is disallowed.

(4)

5

Lawson: A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction

Published by DigitalCommons@EMU, 2012

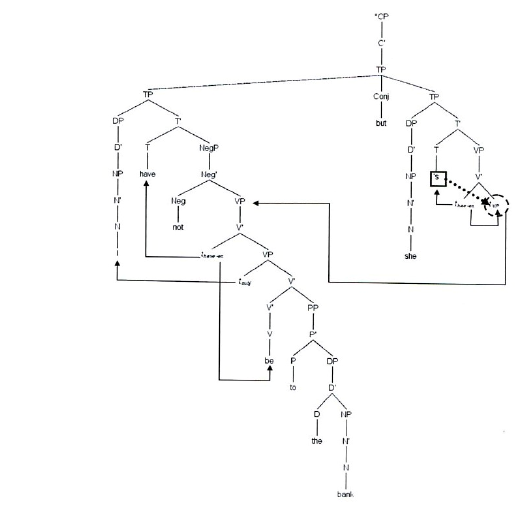

(5) I have not been to the bank, but she [*’s/has].

In example (5), the auxiliary verb “have” mirrors the exact behavior as the copula in

example (2). “Has” must move to “T” to fill the tense position and just as in example (2), the

morpheme is not able to contract because there is no host, on its right, with which to attach itself.

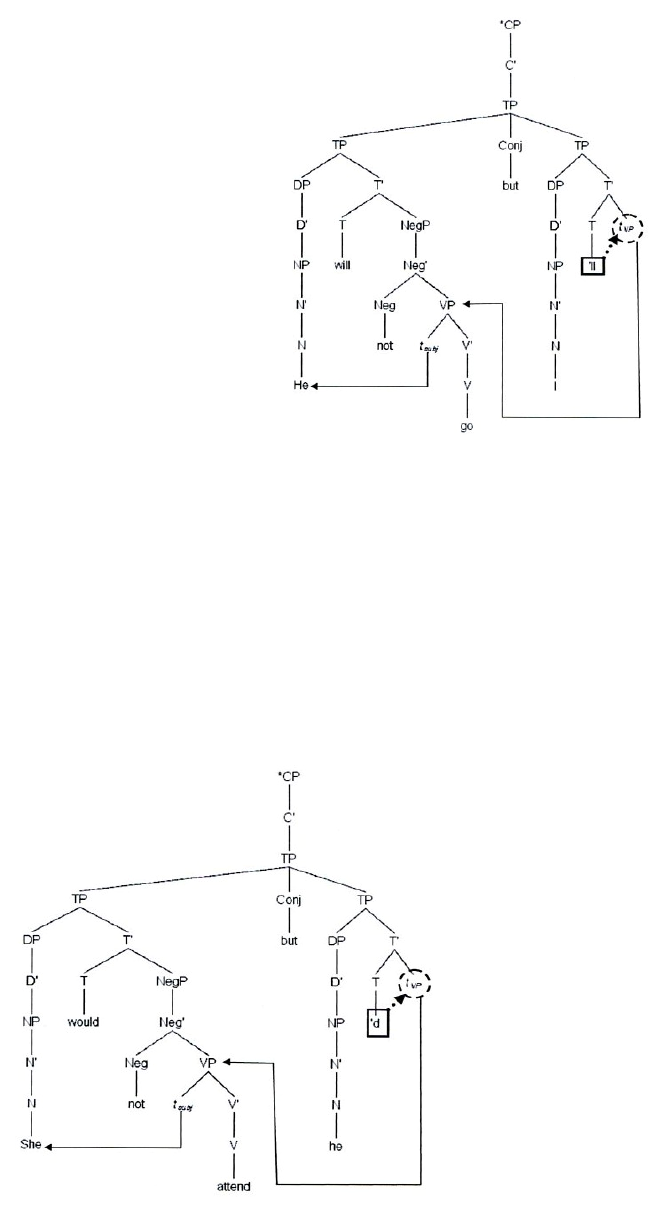

(6) He will not go, but I [*’ll/will].

In example (6), the modal “will” originates in “T,” but it is still unable to contract

because the verb phrase is no longer present. This is what makes the contracted version

ungrammatical.

(5)

6

McNair Scholars Research Journal, Vol. 4 [2012], Art. 5

https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol4/iss1/5

(7) She would not attend, but he [*’d/would].

Example (7) is ungrammatical because it behaves the same as example (6). The modal is

unable to contract because there is nothing to the right which to attach itself

(It appears that, in

English, “would” is only able to contract in the tense position. It is unclear why “would” does

not contract in the complementizer position like “be” and “have” do).

(6)

(7)

7

Lawson: A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction

Published by DigitalCommons@EMU, 2012

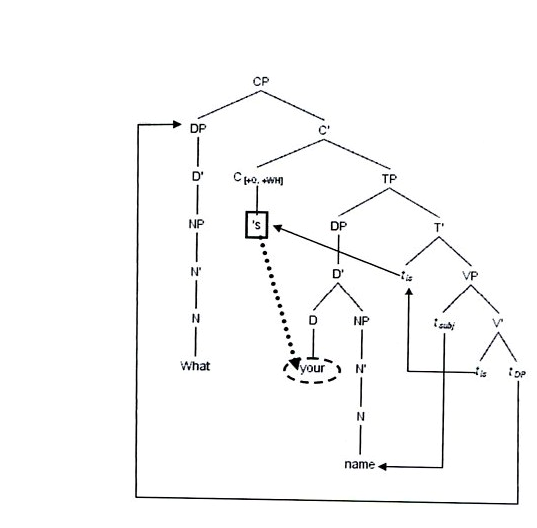

(8) What [‘s/is] your name?

In example (8), “is” must move to “T” to fill the tense position. Once the copula moves to

“T” it acquires tense. The copula must then move again to “C” so that a question may be formed.

It is because the complementizer, represented by “is,” has to pass through the “T” position and

acquire tense before moving to “C” that contraction is possible. As a result, the tensed

complementizer is able to contract and attach itself to a host, located to the right of the

morpheme.

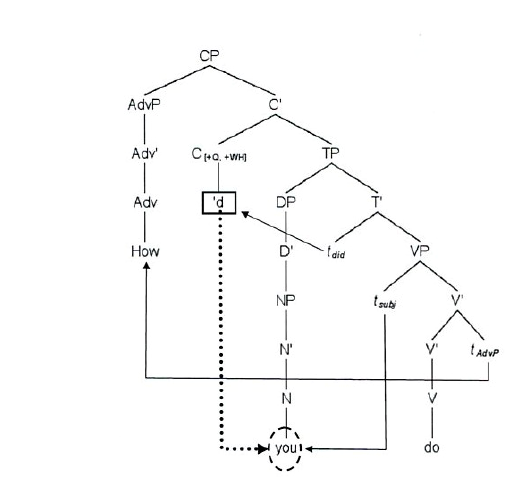

(9) How [‘d/did] you do?

In example (9), “did” has to be inserted in “T” because there are no auxiliary verbs

present that can fill the position. Because “did” originates in “T”, it acquires tense. This allows

“did” to contract and attach to the specifier of “TP” ( It appears that, in English, “do” is only able

to contract in the complementizer position and not in “T.” This may be due to the syntax

inserting “do” last, after realizing that there are no auxiliary verbs present to perform the

necessary movements or fill the necessary spaces. (Ex. *I’d go.)).

(8)

8

McNair Scholars Research Journal, Vol. 4 [2012], Art. 5

https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol4/iss1/5

So far, we have reviewed the basic analysis of tensed be-contraction proposed by Bresnan

and found that her analysis can also be applied to other morphemes that bear tense. However, in

the next section, we will discuss the limitations of Bresnan’s analysis.

Problems with Bresnan’s Analysis

The primary problem with Bresnan’s analysis is that it does not cover other examples of

contraction. Consider the following examples:

“*I wonder where the people’re tonight.” “She did not go to the game, but she should‘ve.” “I

wanna go home.” “*Who do you wanna meet them?” or “I am happy, but she isn’t.”

These examples illustrate the problem: what is the difference between the contractions that work

under Bresnan’s analysis and the ones that do not? We know the contractions that fall under

Bresnan’s analysis contract to the right, but it appears that in the first example, “*I wonder where

the people’re tonight,” that “’re” does in fact have an overt host (tonight) on the right to which it

should attach itself, yet the contracted form is still ungrammatical. In the subsequent examples, it

(9)

9

Lawson: A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction

Published by DigitalCommons@EMU, 2012

appears that the bound morphemes are in fact contracting to the left, instead of to the right. Let

us consider the issues in more detail:

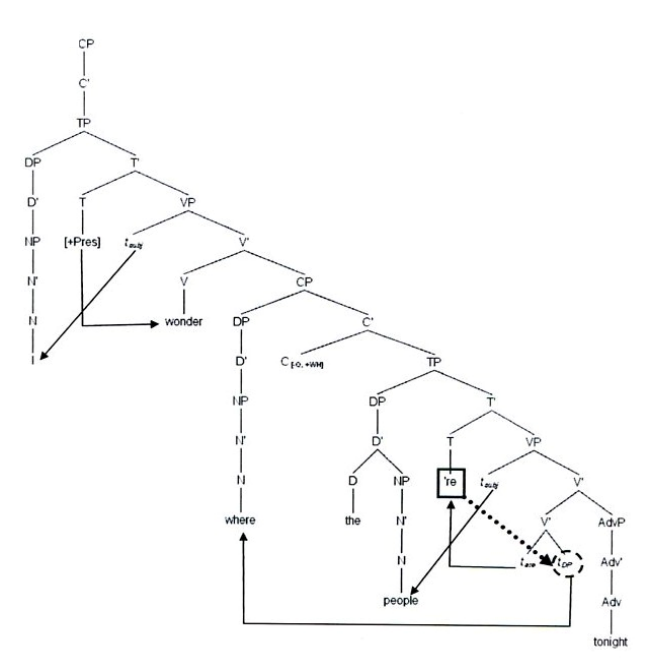

(10) I wonder where the people [*’re/are] (tonight).

In example (10), [+WH] feature takes “’re”s’ true host (where), leaving it nothing which

to attach itself. This is what makes this sentence ungrammatical when contracted.

(11) She did not go to the game, but she should [‘ve/ have].

Although in some cases “have” has to move to “T” in order for tense to be expressed, in

sentence (11), “should” occupies the “T” position and as a result, “have” remains in its VP shell,

making it a tenseless morpheme. As stated early on in this paper, for morphemes to acquire tense

they must originate in “T” (modals), raise to “T” (auxiliary verbs), or pass through “T”

(10)

10

McNair Scholars Research Journal, Vol. 4 [2012], Art. 5

https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol4/iss1/5

(complementizers). Because “have” does not have to raise to “T” it is able to contract to the left

and attach to its host (should) as a suffix.

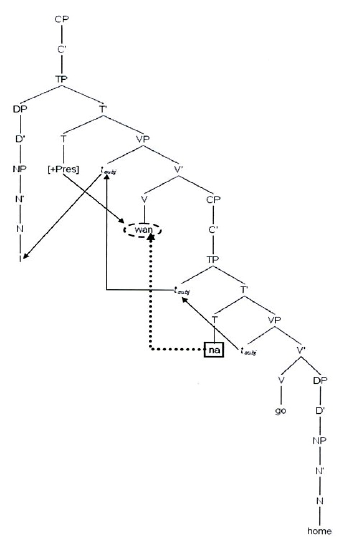

(12) I [want to/wanna] go home.

In example (12), “to” is contracting and attaching itself as a suffix to its host (want) on

the left because “to” is a tenseless morpheme.

(11)

(12)

11

Lawson: A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction

Published by DigitalCommons@EMU, 2012

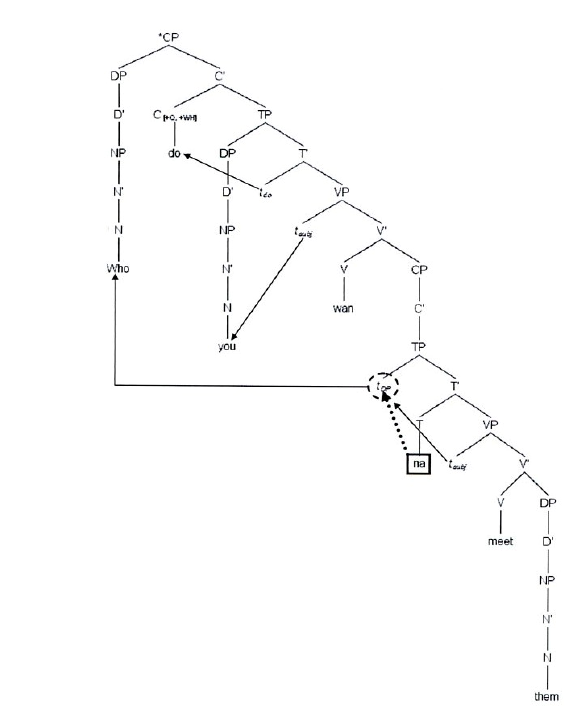

(13) Who do you [*wanna/want to] meet them?”

In example (13), “to” would not contract and attach onto “want” because both “want” and

“to” have different “TP” specifiers. This means that even if this sentence did not have the [+WH]

feature, wanna-contraction would still not be possible. This example is similar in deep structure

to the sentence “You want Jill to meet them.” In the previous sentence, “Jill” blocks “to” from

contracting and attaching onto “want,” just as the “t

DP

” blocks wanna-contraction in example

(13).

12

McNair Scholars Research Journal, Vol. 4 [2012], Art. 5

https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol4/iss1/5

b

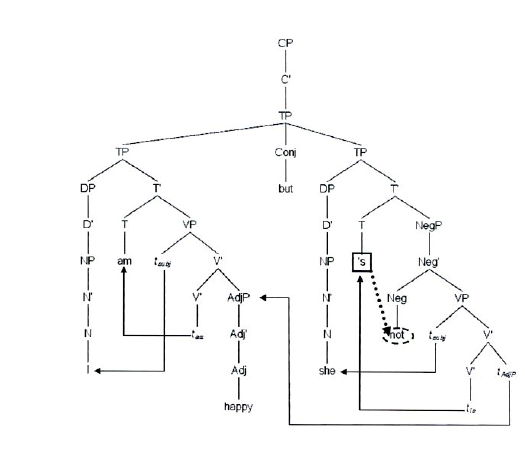

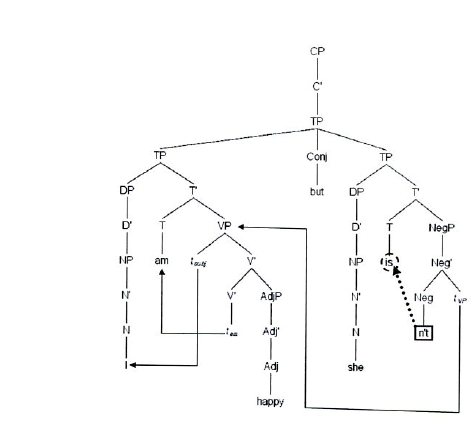

(14) I [‘m/am] happy, but she is [n’t/not].

In example (14), “not” is also a tenseless morpheme. This means that if “not” appears in

the contracted form, it would have to contract to the left, attaching itself to its host (is) as a

suffix.

(13)

13

Lawson: A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction

Published by DigitalCommons@EMU, 2012

At this point, we know that tense plays a major role in determining the direction in which

bound morphemes attach themselves. We see that tenseless morphemes contract and attach

themselves to hosts in the opposite direction of those morphemes that bear tense. We also now

know that it is not enough to state that there must be overt categories located to the right of

tensed bound morphemes or to the left of tenseless bound morphemes. We must note that if trace

elements are located between either of these bound morphemes and the overt categories,

contraction is blocked. The trace elements are the true hosts for these bound morphemes, not the

overt categories that follow the traces, in the case of finite contraction, or those that precede the

traces, as in non-finite contraction. With this information in hand, a new proposal for contraction

will be presented in the following section.

New Proposal

The data provided above shows that there are two procedures for contraction in English.

The first procedure deals with finite contraction. Finite contraction covers the types of

contraction where the contracting morpheme carries tense. In this type, the bound morpheme

must locate a host, on the right, so that it may attach itself as a prefix. The second procedure

(14)

14

McNair Scholars Research Journal, Vol. 4 [2012], Art. 5

https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol4/iss1/5

deals with non-finite contraction. Non-finite contraction covers the types of contraction where

the contracting morphemes are unable to carry tense. In this type, the bound morpheme must

locate a host, on the left, so that it may attach itself as a suffix. However, finite and non-finite

morphemes will not be permitted to contract if certain trace elements (t

VP

, t

DP

, t

AdjP

, etc.) are

located to the right of finite morphemes, or to the left of non-finite morphemes. The

ungrammaticality is a result of the bound morphemes needing to use the trace elements as hosts,

which is impossible because there are no overt hosts present to which the bound morphemes may

attach themselves (at this point, I am unable to explain why contraction is able to bypass

“t

subjects

”. It could possibly be due to “t

subjects

” possessing a case feature).

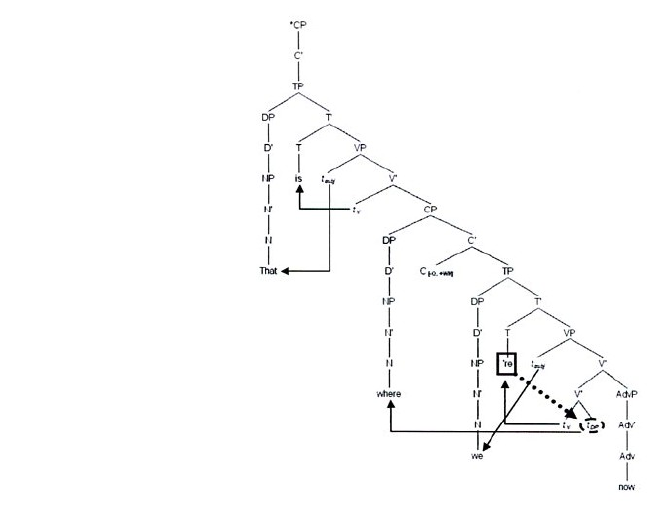

This proposal explains why “*That is where we’re now,” as well as “*You’ren’t going

today,” are ungrammatical, and why “You shouldn’t’ve done that,” is grammatical.

(15) That [‘s/is] where we [*’re/are] now.

In example (15), the [+WH] feature takes “’re’s” host (where), resulting in a “t

DP

” being

located on the right of the bound morpheme. This is why the sentence is ungrammatical.

(15)

15

Lawson: A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction

Published by DigitalCommons@EMU, 2012

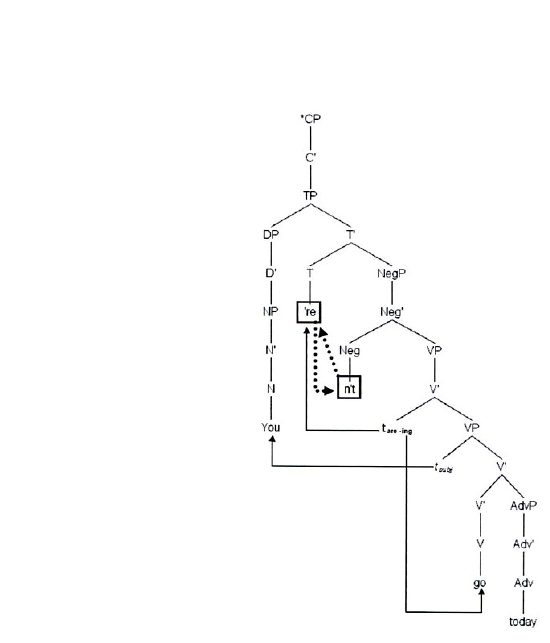

(16) You [*’ren’t/are not] going today.

Example (16) is ungrammatical because “’re” is a bound finite morpheme, while “n’t” is

a bound non-finite morpheme. This means that “’re” is trying to contract and attach itself, as a

prefix, to a host located on the right, while “n’t” is trying to contract and attach itself as a suffix,

to a host located on the left. Ordinarily this would not be a problem, but “’re” is to the left of

“n’t” and “n’t” is to the right of “’re.” Both of these parasitic bound morphemes are relying on

the other to be a free morpheme, which neither are. As a result, the only grammatical

combinations are “You’re not going today” and “You aren’t going today” (This is an exception

to the rule, a finite morpheme and a non-finite morpheme contracting to form a grammatical

sentence (“I’d’ve gone, if I did not have other plans.”)).

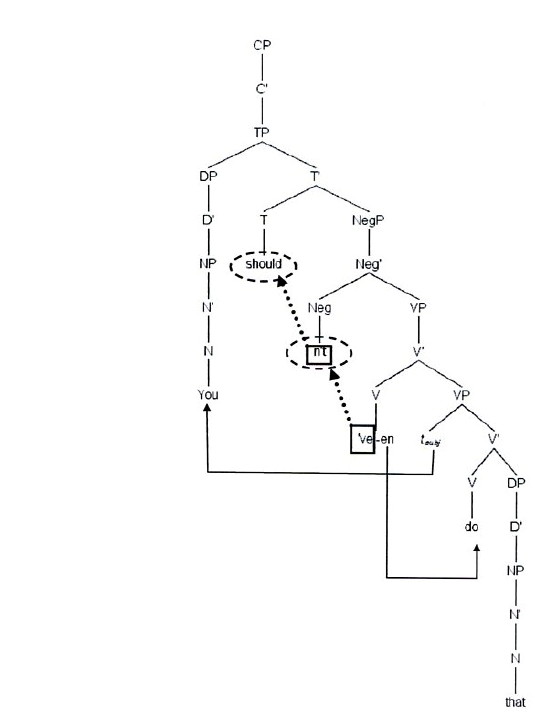

(17) You should [n’t’ve/not have] done that.

(16)

16

McNair Scholars Research Journal, Vol. 4 [2012], Art. 5

https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol4/iss1/5

Example (17) is grammatical because both of the contracted morphemes are non-finite.

This allows them to seek different hosts to which to attach themselves. The bound morpheme,

“’ve,” is able to contract and attach to its host (not) as a suffix, located on the left of the

morpheme. Once “have” has contracted and attached itself to “not” as a suffix, “not” is then able

to contract and attach to its host (should) as a suffix, located to the left of the morpheme.

CONCLUSION

This new information on how contraction works is beneficial to the field of linguistics

because it aids in our understanding of how the English language works. This proposal may

potentially be added to the list of known rules that govern the English language and it also gives

(17)

17

Lawson: A Morpho-syntactic Analysis of Contraction

Published by DigitalCommons@EMU, 2012

linguists more insight into the interactions between the syntax and phonology. Under this

proposal, the syntax sets up the syntactic structure and then determines whether it wants to

perform contraction or not. If the syntax decides to perform contraction, it will then analyze the

structure to determine if contraction is possible. If contraction is permitted, the syntax makes the

appropriate adjustments so that it may provide the structure to the phonology. The phonology

may then analyze it for speech production. Discovering more rules in one language gives

linguists the opportunity to apply these rules to other languages in hopes of finding universal

truths about language as a whole.

REFERENCES

Aoun, Joseph and Lightfoot, David W. “Government and Contraction” Linguistic Inquiry. Vol. 15, No. 3 (1984), pp.

465-473.

Boeckx, Cedric. “A Note on Contraction.” Linguist Inquiry. Vol. 31, No. 2 (2000), pp. 357-366.

Hudson, Richard. “Wanna Revisited” Language. Vol. 82, No. 3 (2006), pp. 604-627.

Ileana, Paul. “On the Topic of Pseudoclefts.” Syntax. Vol. 11, No. 1 (2008), pp. 91–124.

Kaisse, Ellen M. “The Syntax of Auxiliary Reduction in English.” Language. Vol. 59, No. 1 (1983), pp. 93-121.

Pullum, Geoffrey K. “The Morpholexical Nature of English to-Contraction” Language. Vol. 73, No. 1 (1997), pp.

79-102.

Schachter, Paul. “Auxiliary Reduction: An Argument for GPSG.” Linguistic Inquiry. Vol. 15, No. 3 (1984), pp. 514-

523.

18

McNair Scholars Research Journal, Vol. 4 [2012], Art. 5

https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol4/iss1/5